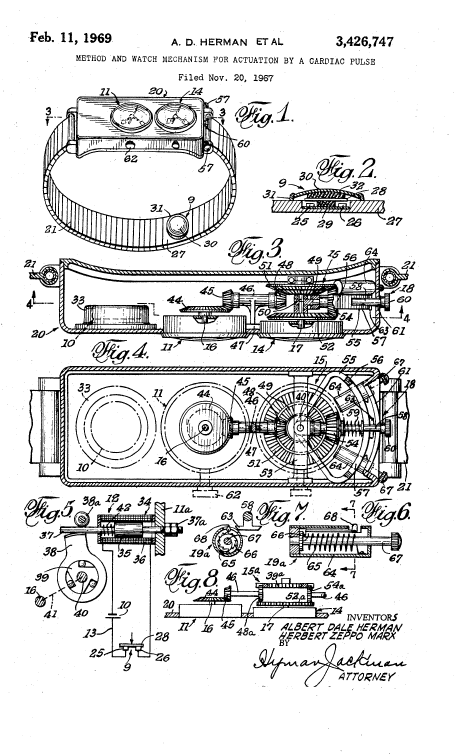

In Alivecor, Inc. v. Apple Inc., [2023-1512, 2023-1513, 2023-1514] (March 7, 2025), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB determination that U.S. Patent Nos.

9,572,499, 10,595,731, and 10,638,941 were unpatentable over certain asserted

prior art.

The Challenged Patents belong to a family of patents related to systems and methods for measuring and analyzing physiological data to detect cardiac arrhythmias. The appeal principally focused on two features of the claims of the Challenged Patents: (1) the use of

machine learning to detect arrhythmias, and (2) the step of confirming the presence of arrhythmias.

The ’499 and ’731 patents broadly contemplate the use of machine learning to detect arrhythmias from ECG data, referencing multiple machine learning operations spanning a diverse range of complexity, ranging from simple operations such as “ranking,” “classifying,” “labelling,” “predicting,” and/or “clustering” data, to more complex operations like “random

forest, association rule learning, artificial neural network, inductive logic programming, [and] support vector machines.” The use of machine learning is recited in dependent claims 7-9 and 17-19 of the ’499 patent and dependent claims 3, 5, 6, 19, and 21-22 of the ’731 patent, but the Federal Circuit pointed out that the description of machine learning in the claims is a a high level of generality, and not clam requires a specific type of machine learning algorithm.

AliveCor raised three main issues on appeal. First, AliveCor argues that the Board erred in finding the machine learning claims were obvious based on Hu 1997 or Li 2012 in combination with Shmueli. Second, AliveCor challenged the Board’s finding that Shmueli rendered the “confirming” step obvious. Finally, AliveCor contended that Apple violated its discovery obligations by failing to produce secondary consideration evidence from a parallel ITC proceeding.

On the challenged to the obviousness of the machine learning claims, the Federal Circuit found that the Board had substantial evidence, including the testimony of Apple’s expert, Dr. Chaitman, for its finding that the teachings of Shmueli combined with Hu 1997 or Li 2012 would have motivated one of ordinary skill in the art to use a machine learning algorithm to detect arrhythmias in the manner claimed. The Federal Circuit said that to restrict each reference’s teachings to the particular way it implements machine learning, as AliveCor

insists argued, would improperly fail to read the references for all that they disclose, citing In re Mouttet, 686 F.3d 1322, 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (“A reference may be read for all that it teaches, including uses beyond its primary purpose.”). The Federal Circuit further said that AliveCor’s approach also conflicted with the reality that the skilled artisan is not an automaton, so it must “take account of the inferences and creative steps that a person of ordinary skill in the art would employ.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 418 (2007). The Federal Circuit concluded that there was nothing improper in the Board’s determination that such an ordinarily skilled artisan would have found it obvious to use machine learning in connection with PPG data, even if this precise use is not expressly disclosed in either Hu 1997 or Li 2012.

Further, the Federal Circuit noted that the Challenged Patents’ machine learning claims, accorded their plain and ordinary meaning in light of the specification, did not require any specific type of machine learning algorithm or a precise method for inputting and analyzing data to detect arrhythmias. Thus, Apple’s burden could be satisfied by substantial evidence that a person of ordinary skill would have found it obvious to use machine learning generally.

The Federal Circuit also found that substantial evidence also supports the Board’s finding

that Shmueli teaches the step of confirming arrythmias using ECG measurements after a potential arrythmia is detected using PPG. The Federal Circuit said that the Board reasonably read portions of Shmueli as teaching a feedback loop in which collected ECG data is used to update the detection parameters used to identify irregularities from incoming

PPG data in real time. The Federal Circuit said that the Board also fairly credited the testimony of Dr. Chaitman, Apple’s expert.

Lastly, as to AliveCor request to vacate the Board’s decisions due to Apple’s failure to comply with Apple’s self-executing discovery obligations, the Federal Circuit found that AliveCor forfeited its argument for failure to raise it with the Board.