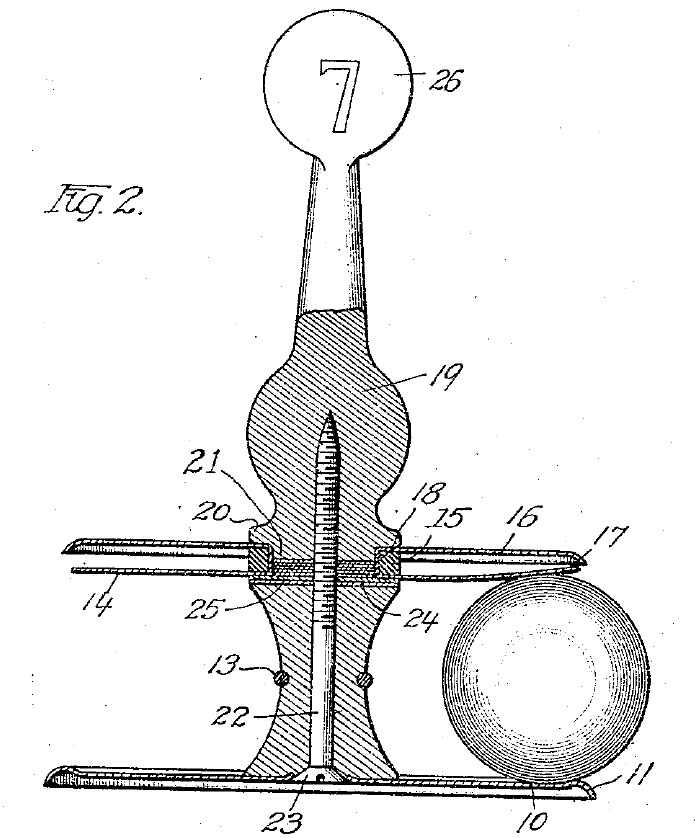

In Young v. Ann Stone, Inc., 1:13-cv-04920 (N.D. Ill. 2014) the district court granted judgment on the pleadings that defendant’s design for a golf practice target:

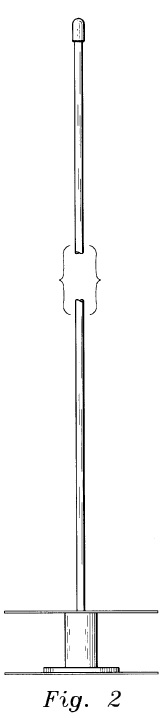

does not infringe U.S. Patent No. D442,661:

“because the two devices are so obviously dissimilar as to warrant a finding of non-infringement as a matter of law”.

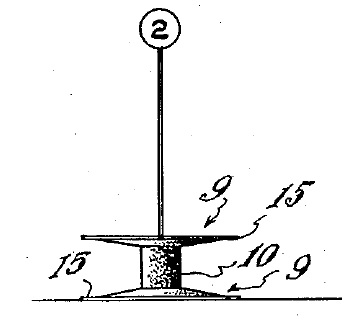

In the words of the court, “[o]ne of the most obvious differences between the products is that top of the lower disk on defendant’s product is noticeably inclined, directing the ball upward to the center where it is held in place. Plaintiff’s design features a flat lower base with what appears to be a washer around the center column that holds the ball. This difference is readily apparent upon even a casual view of the two products.” The court said that the spaced discs were functional and could not serve as the basis for a determination that its product infringes on the patented design, noting that “all of the prior art shares this feature” and finding that it is “the unique mechanisms among the products that contribute to the overall differences in appearance”. In the context of the prior art such as U.S. Patent Nos. 1,297,055 and 2,899,207 , the district court’s decision makes even more sense:

Of note to design practitioners, is that the defendant’s arguments about the cap on the flag pole and the placement of the flag contributed to court’s finding that the designs were different:

Defendant argues that the rounded cap on plaintiff’s flagpole is substantially different from the tapered insert on defendant’s flagpole. The flag of the alleged infringer’s product also covers the top of the flagpole, while the suggested flag on the patented product (which is not a part of the patented design) appears to attach to the pole well below the cap in question, leaving the top of the flagpole visible. When the products are viewed as a whole, this difference adds to the impression that the two products are plainly dissimilar.

Most of the art of design patent drafting is deciding what to show and what not to show, and of what is shown, what is in solid and what is in dashed lines. The court’s discussion of such details is a reminder to the careful prosecutor to pay attention.