37 CFR 1.77(b)(7) suggests that a patent application should include a “Background of the Invention.” However, the Background of the Invention can cause trouble if the drafter is not careful.

The Background of the Invention, sometimes called the “fairy tale” by older practitioners (there are number of examples where the background actually contains the fairy tale beginning “once upon a time”– see U.S. Patent Nos. 7,715,960, 7,207,929, 5,537,417 and 4,206,568), not surprisingly sets for the background information and often identifies the problem(s) solved by the invention.

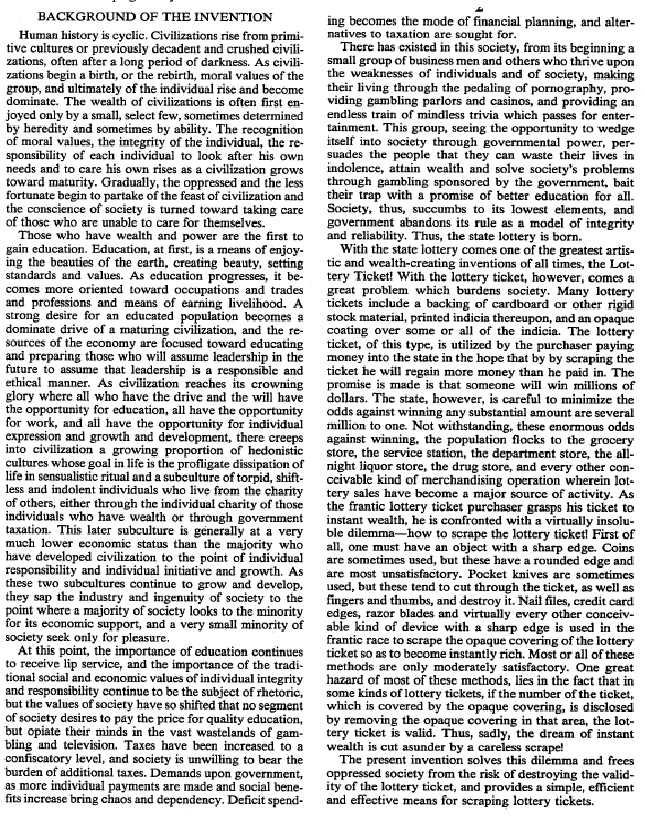

One of the greatest (although not necessarily the best) “backgrounds” in a U.S. patent is found in U.S. Patent No. 4,646,382 on a Lottery Ticket Scraper, where the background ties the subject ticket scraper to the rise of civilization from primitive cultures:

In contract, the best background is probably one that says as little as possible. A background prepared after the invention (and they all are) can tend to make the invention look obvious, describing the problems of the prior art in such a way that the inventor’s solution almost seems obvious. This appears to be the case in the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Intercontinental Great Brands LLC v. Kellogg North American Co., discussed here, where the identification of the problem to be solved in background formed a part of the overall obviousness determination.

The Background of U.S. Patent No. 5,156,594 was used against the patent owner in Scimed Life Sys., Inc. v. Advanced Cardiovascular Sys., Inc., 242 F.3d 1447 (Fed. Cir. 2001), where criticisms of the prior art were used to narrow the claims.

In preparing the background of a patent application,

- Discuss problems of “some” prior devices, rather than “all” prior art.

- Avoid describing the problems of the prior art in a way that makes the invention seem like the obvious extension of the prior art.