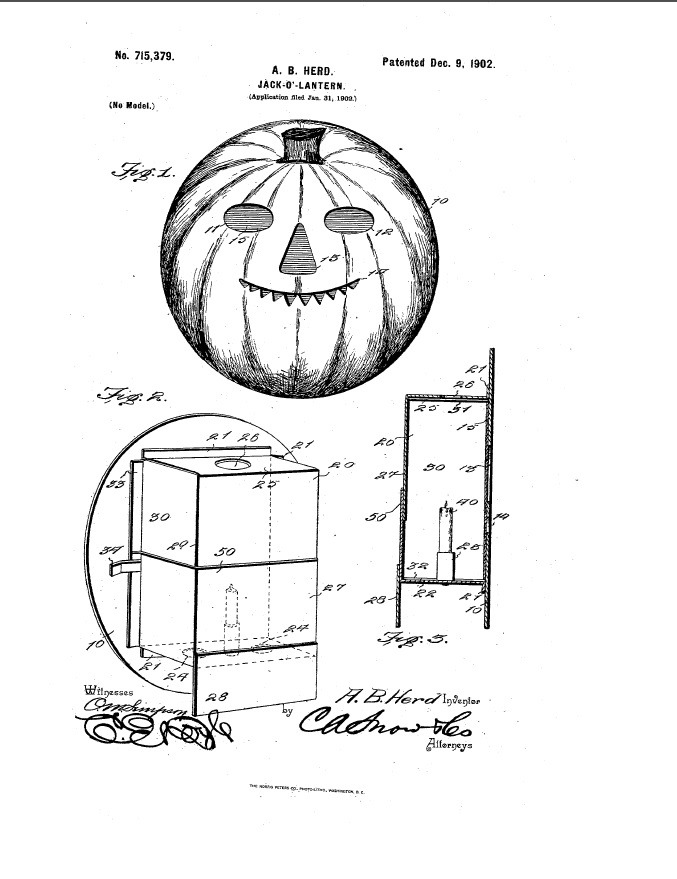

On December 9, 1902 U.S. Patent No. 7157339 issued to A. B. Herd on a Jack-O’-Lantern.

Monthly Archives: October 2018

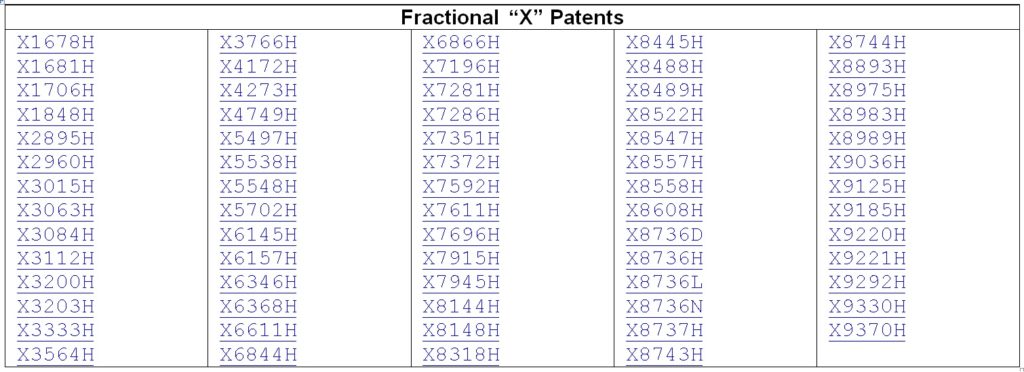

Fractional Patents

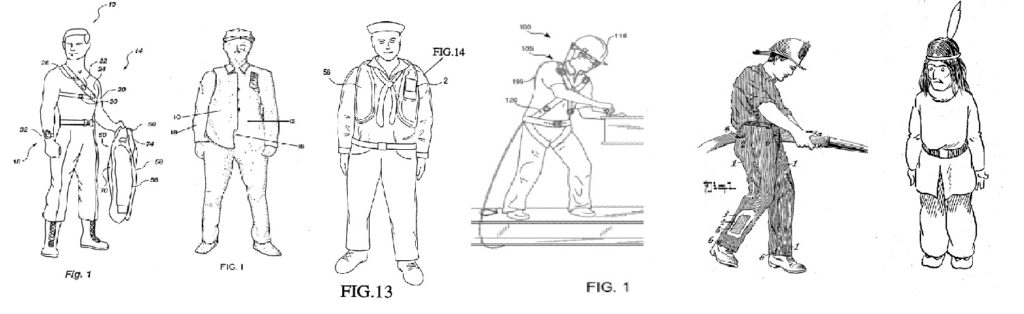

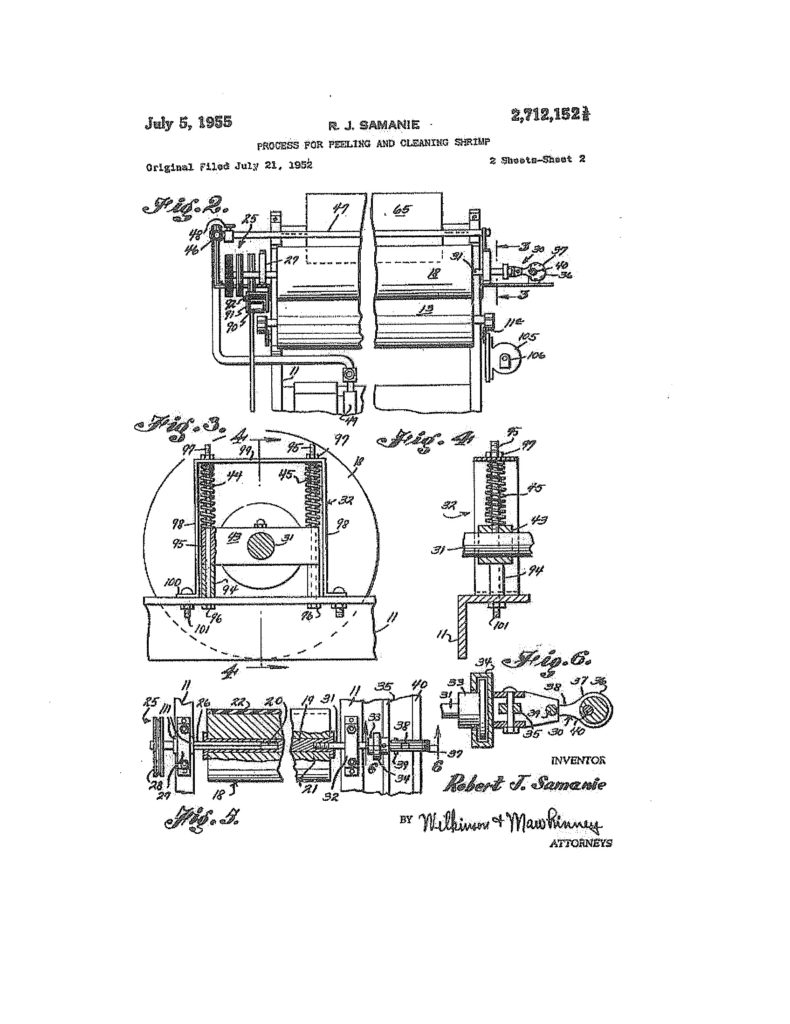

No, a fractional patent is not what you have left over after the PTAB gets a hold of your patent. Fractional patents are actually patents with fractional numbers. The practice started back when the USPTO was trying to reassemble the collection of patents issued before the Office numbered patents. These pre-number era patents are known as the “X” patents, and as the Office was assigning these patents numbers, they would occasionally come across patents whose issue dates were between already numbered patents. In order to keep the chronological sequence, the USPTO needed to issue fractional numbers.

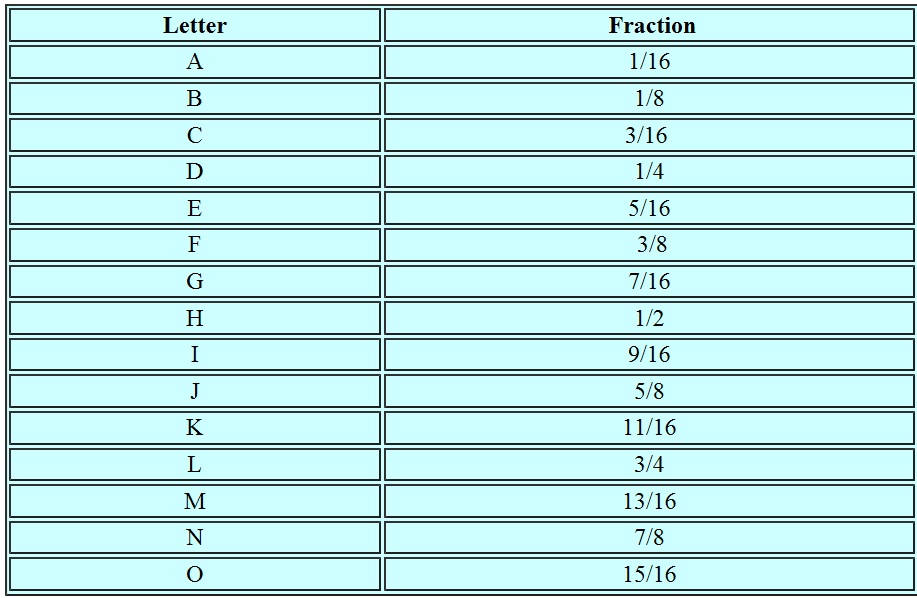

In fact the USPTO even created a letter code system to identify the fractions:

The surprising thing is that the fractional number scheme continued from time to time even after the USPTO began numbering patents. 126½, 1400½, RE1217½, RE1242½, D1093½, 2712152½,  3262124½,

3262124½,

and D90793½.

Goldilocks Prosecution

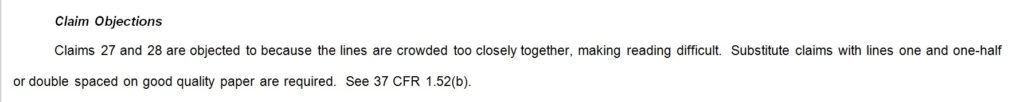

The rules of claim drafting are numerous and arcane. Even after years of prosecution experience, however, it seems there are more to discover.

While the wording of claims is obviously important, recently, several office actions revealed the criticality of the spacing of claims. You don’t want the spacing to be too much:

nor can it be too little.

the spacing needs to be just right.

The Village (Patent) People

The U.S. patent collection is an impressive technical library literally providing solutions to more than 10,000,000 problems. However often overlooked is the fact that it is an also an art gallery of technical drawings from the most basic, such as U.S. Patent No. 448,647 on a Tooth Pick:

to the most intricate, such as U.S. Patent No. 3,398,406 on a Buoyant Bulletproof Combat Uniform, which has drawings worthy of a graphic novel:

One interesting aspect of this “gallery” is how people are depicted in various professions over time. Assembled for the first time below, in homage to another group of varied professionals, are the Village (Patent) People:

who no doubt believe that “it’s fun to stay at the US – P – T – O.”

The Board May Consider Non-Prior Art Evidence in Considering the Knowledge, Motivations, and Expectations of a PHOSITA Regarding the Prior Art.

In Yeda Research and Development Co., Ltd. v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc., [2017-1594, 2017-1595, 2017-1596] (October 12, 2018) the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s determination that U.S. Patent Nos. 8,232,250, 8,399,413, and 8,969,302 unpatentable as obvious.

Yeda contends that its due process rights and the APA were violated because it did not have notice of, and an opportunity to respond to, Khan 2009. The Board relied on Khan 2009 in deciding whether a POSITA would have had a reasonable expectation of success of a thrice-weekly regimen. Yeda received notice of Khan 2009 in Petitioners’ expert reply declaration, attached to Petitioners’ reply. Yeda deposed Dr. Green after receiving his reply declaration; he discussed Khan 2009 in that deposition and was questioned about it. Yeda also moved to exclude Khan 2009 as irrelevant, which the Board denied. Yeda could have, but did not, address Khan 2009 at the oral hearing or

seek leave to file a surreply to substantively respond to Khan 2009.

Based on this record, the Federal Circuit received proper notice of and an opportunity to respond to Khan 2009—an opportunity Yeda took advantage of when it moved to exclude the study. But Yeda contends that it had no notice that the Board “might rely extensively” on Khan 2009 and make it “an essential part of its obviousness analysis.” The Federal Circuit said that although Yeda framed its argument as being about due process, it really only challenges the Board’s use of Khan 2009. The Board acknowledged that Khan 2009 does not qualify as statutory prior art, but because the study began two years before the priority date of the patents, the Board concluded that Khan 2009 is “probative of the fact that those skilled in the art were motivated to

investigate dosing regimens of GA with fewer injections to improve patient compliance.”

The real question before the Federal Circuit was whether the Board may consider non-prior art evidence, such as Khan 2009, in considering the knowledge, motivations, and

expectations of a POSITA regarding the prior art. The Federal Circuit noted that the statute permits IPR petitioners to rely on evidence beyond the asserted prior art. Section 312(a)(3) of Title 35 specifies that a petition should include both “copies of

patents and printed publications that the petitioner relies upon,” and “affidavits or declarations of supporting evidence and opinions.” As do the regulations. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.104(b).

The Federal Circuit said that the Board has recognized that non-prior art evidence of what was known “cannot be applied, independently, as teachings separately combinable” with other prior art, but “can be relied on for their proper supporting roles, e.g., indicating the level of ordinary skill in the art, what certain terms would mean to one with ordinary skill in the art, and how one with ordinary skill in the art would have understood a prior art disclosure.” The Federal Circuit said that the expert’s reliance on Khan 2009 is permissible, as it supports and explains his position that a POSITA would have thought less frequent dosing worthy of investigation as of the priority date. The Federal Circuit found the reliance proper, but to the extent that this reliance was error,

it concluded that it was harmless error, because substantial evidence otherwise

supports the Board’s conclusion.

District Court Did Not Rely on Flawed Obvious to Try Rational

In Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., v. Sandoz Inc., [2017-1575] (October 12, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court decision invalidating for obviousness all asserted claims of patents directed to COPAXONE® 40mg/mL, a product marketed for treatment of patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis.

On appeal, Teva argued the district court improperly discounted the “sufficiency” terms in its claims, construing these terms to be nonlimiting statements of intended effect. The Federal Circuit said that “the regimen being sufficient to reduce the frequency of relapses in the patient” does not change the express dosing amount or method already disclosed in the claims, or otherwise result in a manipulative difference in the steps

of the claims.” The Federal Circuit further found that Teva’s argument that the sufficiency terms were added during prosecution to overcome rejections overstated the intrinsic record. Accordingly the Federal Circuit found no error in the district court’s construction.

As to obviousness, Teva argued for the patentability of its claimed dosing regimen, the improved tolerability, reduced frequency of adverse effects, and the reduced severity of injection site reactions.

The Federal Circuit rejected Teva’s argument that the district court engaged in an improper obvious to try analysis. An “obvious to try” analysis is improper if it suggests varying all parameters or try every available option until one succeeds, where the prior art gave no indication of critical parameters and no direction as to which of many possibilities is likely to be successful. An “obvious to try” analysis is involves a new technology or general approach in a seemingly promising field of experimentation, but the prior art gives only general guidance as to the particular form or method of

achieving the claimed invention. The Federal Circuit said that neither of these was what the district court did — the prior art focused on two critical variables, dose size and injection frequency, and provided clear direction as to choices likely to be successful in

reducing adverse side effects and increasing patient adherence.

Teva contends that the unpredictable nature of the compound categorically precludes the obvious-to-try analysis employed by the district court. Again the Federal Circuit disagreed, noting obviousness was proven through human clinical studies establishing the safety, efficacy, and tolerability at doses and dose frequencies similar to the claimed regimen.

Regarding improved tolerability and reduced frequency, Teva argued that the prior art did not lead POSITAs to expect improved tolerability and reduced frequency of

injection reactions from the claimed regimen compared to the prior art, but the Federal Circuit disagreed. Teva found fault with the district court’s reference to “common sense” in its reliance on expert testimony, and argued that the expert testimony was conclusory and unsupported by the prior art. The Federal Circuit found no error in what is essentially a credibility determination.

On reduced severity, the Federal Circuit again agreed with the district court that the evidence provided a reasonable expectation to those skilled in the art that reducing the number of injections per week may also reduce the severity of injection site reactions.

Primers and the Use of Naturally Occurring Position-Specific Signature Nucleotides are Patent Ineligible

In Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., v. Cepheid, [2017-1690] (October 9, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment of invalidity of claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,643,723 as directed to patent ineligible subject matter.

The ’723 patent is directed to methods for detecting the pathogenic bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The ’723 patent provides two types of claims: (1) composition-of-matter claims for the primers used in the PCR, which could hybridize to the rpoB gene of MTB at a site that includes at least one of the eleven signature nucleotides (“the primer claims”); and (2) process claims for methods for detecting MTB that include amplifying target sequences by PCR and detecting amplification products,

which, if present, indicate the presence of MTB (“the method claims”).

As to the primer claims, the Federal Circuit held that In re BRCA1 foreclosed Roche’s arguments for patentability. There, the Federal Circuit examined the subject matter eligibility of similar primer claims and held that those primers were not distinguishable

from the isolated DNA found patentineligible in Myriad” and thus are not patent-eligible. Primers necessarily contain the identical sequence of the nucleotide sequence directly opposite to the DNA strand to which they are designed to bind. The subject matter eligibility inquiry of primer claims hinges on comparing a claimed primer to its corresponding DNA segment on the chromosome—not the whole chromosome.

As to the method claims, the Federal Circuit said that the claims disclose a diagnostic test based on the observation that the presence of the eleven position-specific signature nucleotides of the naturally occurring MTB rpoB gene indicates the presence

of MTB in a biological sample. The method claims are directed to a relationship between the eleven naturally occurring position-specific signature nucleotides and the

presence of MTB in a sample. In other words, the method claims assert that if an investigator detects a signature nucleotide from a sample, she knows the sample contains MTB. This relationship between the signature nucleotides and MTB is a phenomenon that exists in nature apart from any human action, meaning the method claims are directed to a natural phenomenon, which itself is ineligible for patenting.

Details Save Claims from Invalidity Under Section 101

In Data Engine Technologies LLC v. Google LLC, [2017-1135] (October 9, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed in part, reversed in part, and remanded, entry of judgment on the pleadings holding that the asserted claims of DET’s U.S. Patent Nos. 5,590,259; 5,784,545; 6,282,551; and 5,303,146 are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The Federal Circuit concluded that with the exception of claim 1 of the ’551 patent, the asserted claims of the ’259, ’545, and ’551 patents are directed to patent-eligible subject matter, finding that these claims claims are not abstract, but rather are directed to a

specific improved method for navigating through complex three-dimensional electronic spreadsheets. The Federal Circuit agreed that the asserted claims of the ’146 patent,

reciting methods for tracking changes to data in spreadsheets, were directed to the abstract idea of collecting, recognizing, and storing changed information.

Regarding the ’259, ’545, and ’551 patents, the Federal Circuit said that the claimed method does not recite the idea of navigating through spreadsheet pages using buttons or a generic method of labeling and organizing spreadsheets. Rather, the claims require a specific interface and implementation for navigating complex three-dimensional spreadsheets using techniques unique to computers.