In Campbell Soup Company v. Gamon Plus, Inc., [2018-2029, 2018-2030] (September 26, 2019) the Federal Circuit affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded, Board determinations that U.S. Patent Nos. D612,646 and D621,645 were nonobvious from the cited prior art.

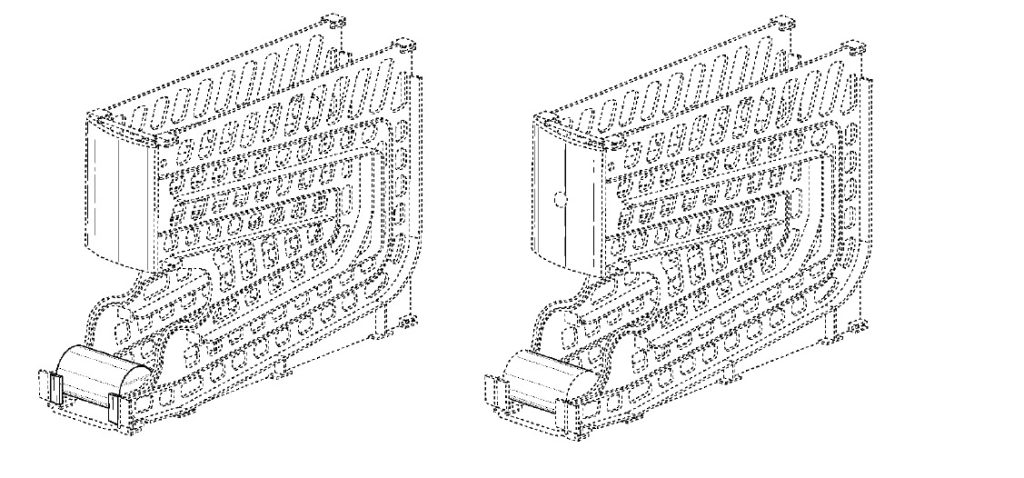

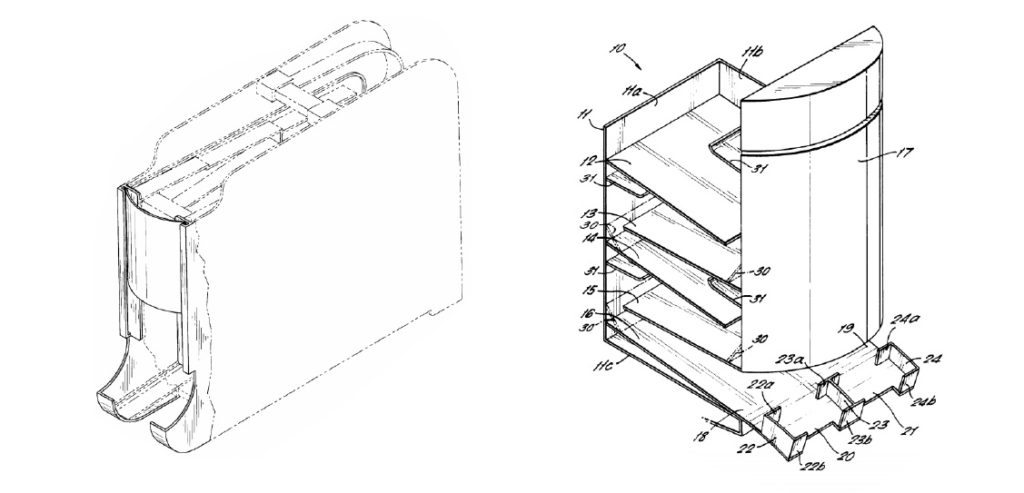

The ‘645 and ‘646 patents are directed to ornamental design for a gravity feed dispenser display.

The figures are identical except that the edges at the top and bottom of the cylindrical object lying on its side and the stops at the bottom of the dispenser are shown in broken lines in the ‘645 patent, and there is a small circle shown in broken lines near the middle of the label area.

Campbells filed IPR against both designs, arguing that the designs were obvious in view of (1) Linz in view of Samways, (2) Samways, or (3) Samways in view of Linz.

The Board held that Campbells did not establish unpatentability by a preponderance of the evidence because it found that neither Linz nor Samways was similar enough to the claimed designs to constitute a proper primary reference.

In the design patent context, the ultimate inquiry under section 103 is whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved. To determine whether one of ordinary skill would have combined teachings of the prior art to create the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design, the fact finder must first find a single reference, a something in existence, the design characteristics of which are basically the same as the claimed design. To identify a primary reference, one must: (1) discern the correct visual impression created by the patented design as a whole; and (2) determine whether there is a single reference that creates “basically the same” visual impression. If a primary reference exists, related secondary references may be used to modify it.

The Board found that Linz was not a proper primary reference because it does not disclose any object, including the size, shape, and placement of the object in its display area and fails to disclose a cylindrical object below the label area in a similar spatial relationship to the claimed design. The Federal Circuit reversed for lack of substantial evidence support. Accepting the Board’s description of the claimed designs as correct, the Federal Circuit found that the ever-so-slight differences in design, in light of the overall similarities, do not properly lead to the result that Linz is not “a single reference that creates ‘basically the same’ visual impression” as the claimed designs.

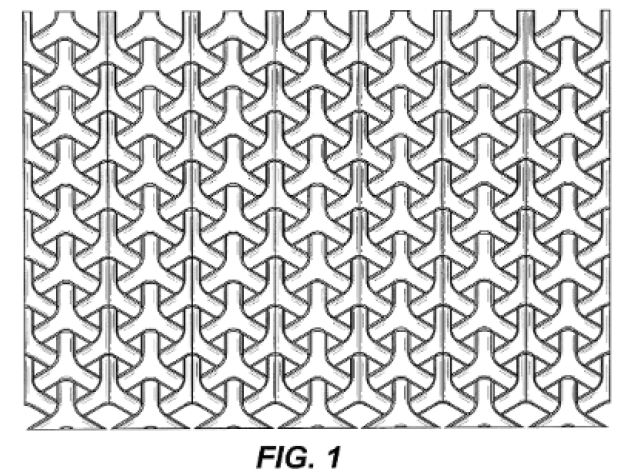

The Board also found that Samways was not a proper primary reference. The Board found that significant modifications would first need to be made to Samways’ design, such as combining two distinct embodiments of the utility patent, which was “not a design in existence.” The Board found that considering the designs as a whole, the design characteristics of Samways are not basically the same as the claimed design. The Federal Circuit agreed, saying accepting the Board’s description of the claimed designs as correct, substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Samways is not a proper primary reference. The Federal Circuit noted numerous differences, and concluded that given these differences, substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Samways does not create basically the same visual impression as the claimed designs.

The Federal Circuit remanded the case to the Board to consider obviousness with Linz as a primary reference.