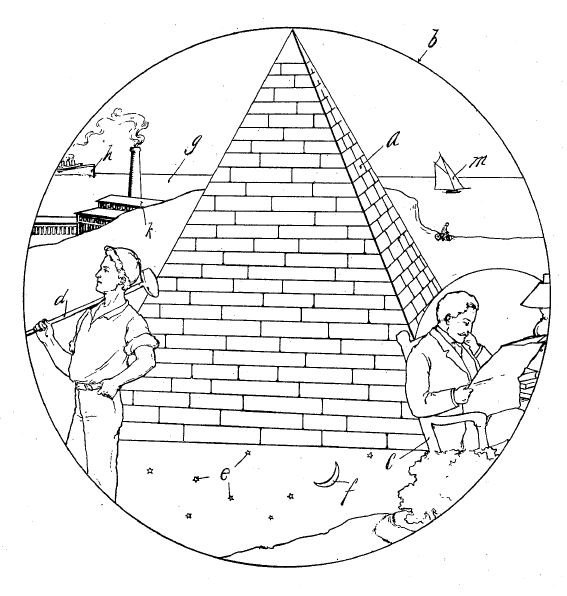

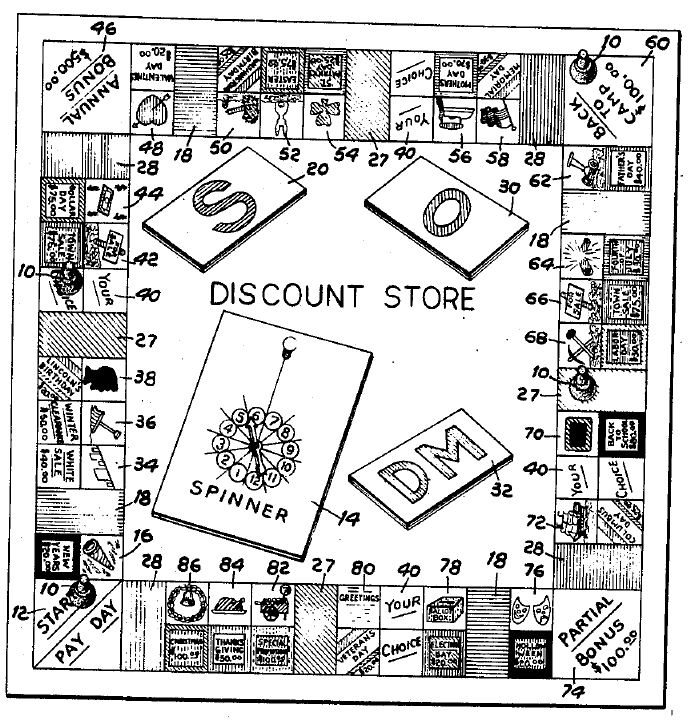

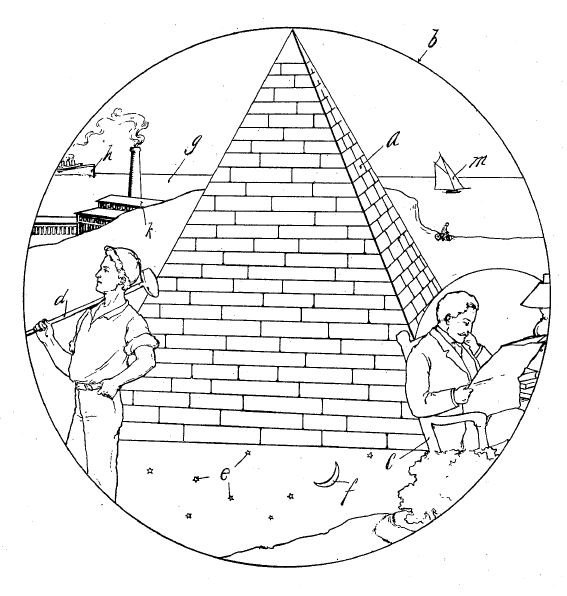

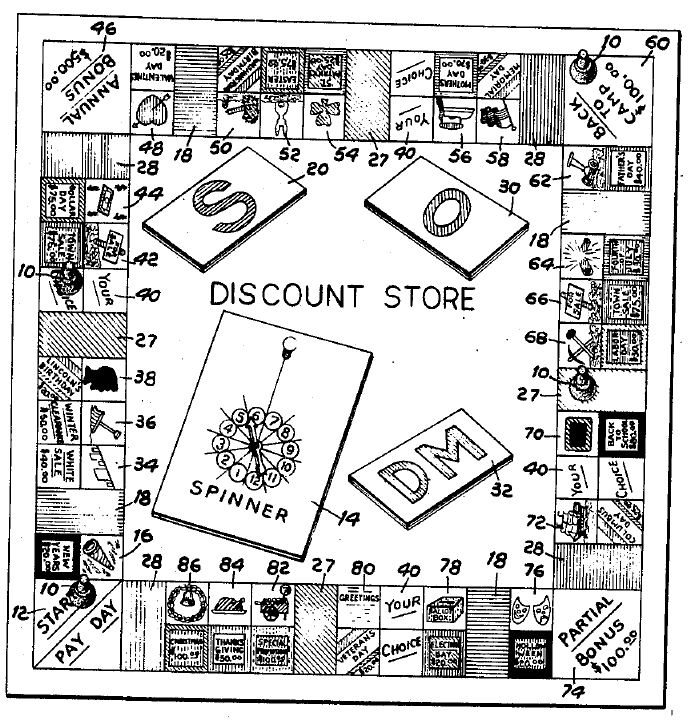

A number of patents mention Labor Day, most of these relate to calendars or calendar-based games.

celebrates the laborer

A number of patents mention Labor Day, most of these relate to calendars or calendar-based games.

The as of last Tuesday, August 20, 2019, the USPTO issued U.S. Patent 10,390,470. That would seem to be the answer. A patent nerd would remember, however, that before patents were numbered about 9,957 patents — called the X patents — issued. A serious patent nerd would further know that as of August 20, 2019, for one reason or another, more than 48721 numbers did not correspond to issued patents. An uber patent nerd would know about factional patents, patents with fractional numbers issued between patents with whole numbers. There are at least four fractional patents in the era when patents were numbered.

So as of August 20, and until the next batch on August 27, the number may be 10,351,710.

In Mymail, Ltd. v. Oovoo, LLC, [2018-1758, 2018-1759] (August 16, 2019), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded judgment on the pleadings, the district court erred by declining to resolve the parties’ claim construction dispute before adjudging patent eligibility.

The district court found U.S. Patent Nos. 8,275,863 and 9,021,070 were directed to patent ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The district court concluded that the MyMail patent claims are directed to an abstract idea because they “fall within the category of gathering and processing information” and “recite a process comprised of transmitting data, analyzing data, and generating a response to transmitted data.” At Alice step two, the district court concluded that the claims fail to provide an inventive concept sufficient to save the claims.

The Federal Circuit said that Patent eligibility may be determined on a Rule 12(c) motion, but only when there are no factual allegations that, if taken as true, prevent resolving the eligibility question as a matter of law. The Federal Circuit said that determining patent eligibility requires a full under-standing of the basic character of the claimed subject matter. As a result, if the parties raise a claim construction dispute at the Rule 12(c) stage, the district court must either adopt the non-moving party’s constructions or resolve the dispute to whatever extent is needed to conduct the § 101 analysis.

Before the district court, the parties disputed the construction of “toolbar,” a claim term present in the claims of both MyMail patents. MyMail directed the district court to a construction of “toolbar” rendered in another case involving the MyMail patents. The Federal Circuit noted that the district court never addressed the parties’ claim construction dispute. Nor did the district court construe “toolbar” or adopt MyMail’s proposed construction of “toolbar” for purposes of deciding ooVoo’s and IAC’s Rule 12(c) motions.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court erred by failing to address the parties’ claim construction dispute before concluding, on a Rule 12(c) motion, that the MyMail patents are directed to patent-ineligible sub-ject matter under § 101, and vacated and remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

In Anza Techttp://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/opinions-orders/19-1045.Opinion.8-16-2019.pdfhnology, Inc. v. Mushkin, Inc., [2019-1045](August 16, 2019), the Federal Circuit reversed in part, vacated in part, and remanded, the district court determination that Anza’s second amended complaint was time barred by 35 U.S.C. § 286’s six year statute of limitations.

The district court granted Mushkin’s motion, ruling that the new infringement claims did not relate back to the date of the original complaint. The court explained that new infringement claims relate back to the date of the original complaint when the claims involve the same parties, the same products, and similar technology—i.e., when the claims are “part and parcel” of the original complaint. The court ruled that newly asserted claims of infringement do not relate back if the new claims are not an integral part of the claims in the original complaint and if proof of the new claims will not entail the same evidence as proof of the original claims. Because Anza acknowledged that Mushkin’s allegedly in-fringing activity all took place more than six years before the filing date of the second amended complaint, the court held that the effect of ruling that the second amended com-plaint did not relate back to the filing date for the original complaint was that all the asserted claims in the second amended complaint were time-barred.

At the outset, the Federal Circuit adopted the majority rule that the application of the relation back doctrine is reviewed de novo, while any underlying facts are reviewed for clear error.

The Federal Circuit notes that the Supreme Court interprets the relation back doctrine liberally, applying if an amended pleading relates to the same general conduct, transaction and occurrence as the original pleading, and that its predecessor, the Court of Claims, embraced a liberal, notice-based interpretation of Rule 15(c). The Federal Circuit said that that pertinent considerations bearing on whether claims are logically related include the overlap of parties, products or processes, time periods, licensing and technology agreements, and product or process development and manufacture. In determining whether newly alleged claims, based on separate patents, relate back to the date of the original complaint, the Federal Circuit said it would consider the overlap of parties, the overlap in the accused products, the underlying science and technology, time periods, and any additional factors that might suggest a commonality or lack of commonality between the two sets of claims.

The Federal Circuit rejected Mushkin’s argument that the withdrawal of all claims of infringement of the ‘927 patent indicates that the claims address different bonding techniques, noting that the asserted patent all share “the same underlying technology, . . . solving the same problem by the same solution.”

The Federal Circuit said that amended claims do not have to be the same as the original claims to relate back. Rather, the claims must arise out of the same conduct, transaction, or occurrence. The Federal Circuit concluded that the products implicated by all three complaints did relate back, but that the newly added products may not, unless they are sufficiently related. The Federal Circuit reversed as to the six products implicated by the original complaint, and remanded as to the two products added by the Second Amended Complaint.

In Nalpropion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Actavis Laboratories FL, Inc., [2018-1221] (August 15, 2019), the Federal Circuit held that the district court did not err in finding claim 11 of the U.S. Patent 8,916,195 patent not invalid for lack of written description, but did err in finding that claim 1 of the ’111 patent and claims 26 and 31 of the U.S. Patent 7,462,626 patent would not have been obvious in view of the prior art.

The ’195 patent is also directed to methods of treating overweight or obesity, but the claims are drawn to specific dosages of sustained-release naltrexone and bupropion that achieve a specific dissolution profile. The Federal Circuit conclude that the district court did not clearly err in finding that the inventors had possession of the invention consisting of treating overweight and obesity with the stated amounts of bupropion. The district court found that irrespective of the method of measurement used, the specification shows that the inventors possessed the invention of treating overweight or obesity with naltrexone and bupropion in particular amounts and adequately described it. The Federal Circuit concluded that this finding did not present clear error.irrespective of the method of measurement used, the specification shows that the inventors possessed the invention of treating overweight or obesity with naltrexone and bupropion in particular amounts and adequately described it.

The test for sufficiency is whether the disclosure of the application relied upon reasonably conveys to those skilled in the art that the inventor had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date. It is not necessary that the exact terms of a claim be used in haec verba in the specification, and equivalent language may be sufficient. The Federal Circuit noted that while as a general matter written description may not be satisfied by so-called equivalent disclosure, in the present case, buttressed by the district court’s fact-finding, and where the so-called equivalence relates only to resultant dissolution parameters rather than operative claim steps, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s conclusion, noting “rigidity should yield to flexible, sensible interpretation.

The ’111 patent is directed to a composition of sustained-release bupropion and naltrexone for affecting weight loss, and the ’626 patent is drawn to a method for treating over-weight or obesity comprising. Although the district court found the claims non-obvious, in the Federal Circuit’s view, the prior art disclosed the claimed components of the composition claims and the steps of the method claims including the use claimed by the method.

Nalpropion argued that bupropion does not possess sufficient weight loss efficacy to obtain FDA approval by itself, but the Federal Circuit said that motivation to combine may be found in many different places and forms; it cannot be limited to those reasons the FDA sees fit to consider in approving drug applications. Instead, the court should consider a range of real-world facts to determine whether there was an apparent reason to combine the known elements in the fashion claimed by the patent at issue.

The Federal Circuit said that the inescapable, real-world fact here is that people of skill in the art did combine bupropion and naltrexone for reductions in weight gain and reduced cravings—goals closely relevant to weight loss. Contrary to Nalpropion’s view, persons of skill did combine the two drugs even without understanding bupropion’s mechanism of action but with an understanding that bupropion was well-tolerated and safe as an antidepressant. Thus, the Federal Circuit concluded that skilled artisans would have been motivated to combine the two drugs for weight loss with a reasonable expectation of success. The Federal Circuit examined the claims, and concluded that every limitation in the claims at issue was met by the prior art.

The Federal Circuit then examined objective indicia of nonobviousness. Nalpropion argues that many others tried and failed to find a combination effective for weight loss and that the claimed combination exhibited un-expected results, but the Federal Circuit found that a combination drug that affected weight loss—could not have been unexpected. The Federal Circuit said that the failure of others alone cannot overcome the clear record that the combination of the two drugs was known and that both drugs would have been understood to be useful for claimed purpose.

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision on written description, but reversed the district court’s decision that the claims were not obvious.

In Sanofi-Aventis U.S., LLC v. Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc., [2018-1804, 2018-1808, 2018-1809] (August 14, 2019), the Federal Circuit affirmed the determination that claims 1 and 2 of U.S. Patent No. 5,847,170 were not invalid for obviousness.

The Federal Circuit noted that in cases involving new chemical compounds, it remains necessary to identify some reason that would have led a chemist to modify a known compound in a particular manner to establish prima facie obviousness of a new claimed compound. The reason need not be the same as the patentee’s or expressly stated in the art, but charting a path to the claimed compound by hindsight is not enough to prove obviousness. The Federal Circuit observed that any compound may look obvious once someone has made it and found it to be useful, but working backwards from that compound, with the benefit of hindsight, once one is aware of it does not render it obvious.

In its obviousness analysis, the district court considered the testimony of seven witnesses and seventeen prior art references and ultimately concluded that Defendants failed to prove that claims 1 and 2 of the ’170 patent would have been obvious. In addition, the district court found that some secondary considerations evidence supported nonobviousness and that there was a nexus between claims 1 and 2 and the marketed product Jevtana®. The Federal Circuit agreed with Sanofi and concluded that Fresenius’s “convoluted” obviousness theory lacks merit. The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court did not clearly err in its assessment of these references or in finding that they would not have motivated a skilled artisan to modify the lead compound to achieve the claimed compound.

In Iridescent Networks, Inc. v. AT&T Mobilitiy, LLC, [2018-1449] (August 12, 2019), the Federal Circuit affirmed judgment of non-infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,036,119, on System and Method of Providing Bandwidth on Demand, affirming the district court’s construction of “high quality of service connection.”

The ’119 patent discloses a system and method for managing network traffic routes and bandwidth availability to minimize adverse network conditions and to assure that the network connection maintains a requested minimum level of one of these three parameters. Iridescent proposed broadly construing the claim term “high quality of service connection” to mean “a connection in which one or more quality of service connection parameters, including bandwidth, latency, and/or packet loss, are assured from end-to-end based on the requirements of the application.” The magistrate judge, however, largely adopted AT&T’s proposed construction, construing the term to mean “a connection that assures connection speed of at least approximately one megabit per second and, where applicable based on the type of application, packet loss requirements that are about 10-5 and latency requirements that are less than one second.”

The Federal Circuit began with the language of the claims. The district court found that “high quality of service connection” is a coined term that has no ordinary meaning in the industry, and the Federal Circuit agreed. Because the claim was silent as to what amount of quality is sufficient to be “high,” the Federal Circuit looked first to the specification, followed by the prosecution history, to determine the meaning of the term “high quality of service connection.”

The applicant of the ’119 patent relied on Figure 3 during prosecution to support an amendment that gave rise to the term “high quality of service connection.” Figure 3 indicates minimum requirements for connection speed, packet loss, and latency. During prosecution of the parent application, the applicant argued that “the various connection parameters illustrated for high quality of service enabled bandwidth applications in Fig. 3” supported the term “high quality of service connection.” The Federal Circuit found the applicant relied on the minimum connection parameter requirements described in Figure 3 to overcome the examiner’s §112 enablement rejection.

The Federal Circuit rejected the patent owner’s argument that the prosecution history was not relevant in the absence of clear disavowal, noting that any explanation, elaboration, or qualification presented by the inventor during patent examination is relevant, for the role of claim construction is to capture the scope of the actual invention that is disclosed, described, and patented. The Federal Circuit said that where there is no clear ordinary and customary meaning of a coined term of degree, it may look to the prosecution history for guidance without having to first find a clear and unmistakable disavowal.

The Federal Circuit also rejected the argument that statements made in response to an enablement rejection do not affect claim scope. Noting that the enablement requirement prevents claims broader than the disclosed invention.

The Federal Circuit affirmed the District Courts claim construction.

In MTD Products Inc. v. Iancu, [2017-2292] (August 12, 2019), the Federal Circuit vacated the Board’s obviousness determination, finding that the Board erred in finding that the term “mechanical control assembly” was not a means-plus-function term governed by § 112, ¶ 6.

U.S. Patent No. 8,011,458 discloses a steering and driving system for zero turn radius (“ZTR”) vehicles. Both of the independent claims contain the phrase “mechanical control assembly.”

The “essential inquiry of whether a claim element invokes § 112, ¶ 6. is not merely the presence or absence of the word ‘means’ but whether the words of the claim are understood by persons of ordinary skill in the art to have a sufficiently definite meaning as the name for structure. One way to demonstrate that a claim limitation fails to recite sufficiently definite structure is to show that, although not employing the word “means,” the claim limitation uses a similar nonce word that can operate as a substitute for “means” in the context of § 112, para. 6.” Generic terms like “module,” “mechanism,” “element,” and “device” are commonly used as verbal con-structs that operate, like “means,” to claim a particular function rather than describe a sufficiently definite structure. Even if the claims recite a nonce term followed by functional language, other language in the claim might inform the structural character of the limitation-in-question or otherwise impart structure to the claim term.

In assessing whether the claim limitation is in means-plus-function format, we do not merely consider an introductory phrase (e.g., “mechanical control assembly”) in isolation, but look to the entire passage including functions performed by the introductory phrase. The ultimate question is whether the claim language, read in light of the specification, recites sufficiently definite structure to avoid § 112, ¶ 6.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that the term “mechanical control assembly” is similar to other generic, black-box words that it has held to be nonce terms similar to “means” and subject to § 112, ¶ 6 because the term does not connote sufficiently definite structure to one of ordinary skill in the art. The Federal Circuit further agreed that the rest of the claim language of the disputed phrase is primarily, but not entirely, functional. However the Federal Circuit said that the Board erred when it relied on the specification’s description of a “ZTR control assembly” to conclude that the claim term “mechanical control assembly” had an established structural meaning. The fact that the specification discloses a structure corresponding to an asserted means-plus-function claim term does not necessarily mean that the claim term is understood by persons of ordinary skill in the art to connote a specific structure or a class of structures.

The Federal Circuit found that the Board’s analysis implied that so long as a claim term has corresponding structure in the specification, it is not a means-plus-function limitation. This view would leave § 112, ¶ 6 without any application, because any means-plus-function limitation that met the statutory requirements, i.e., which includes having corresponding structure in the specification, would end up not being a means-plus-function limitation at all.

The Federal Circuit also disagreed with the Board’s interpretation of the prosecution history, finding that arguing that a limitation connotes structure and has weight is not inconsistent with claiming in means-plus-function format since means-plus-function limitations connote structure.

Given the lack of any clear and undisputed statement foreclosing application of § 112, ¶ 6, we conclude that the Board erred in giving dispositive weight to the equivocal statements it cited in the prosecution history.

In Eli Lilly and Co. v. Hospira, Inc., [2018-2126, 2018-2127] (August 9, 2019), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s finding of literal infringement in the Hospira Decision as clearly erroneous in light of the court’s claim construction of “administration of pemetrexed disodium,” but affirmed the district court’s finding of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.

Lilly markets the compound pemetrexed in the form of a disodium salt as Alimta®, for treating certain types of non-small cell lung cancer and mesothelioma. This product was covered by U.S. Patent 7,772,209. Hospira and Dr. Reddy’s each filed ANDA applications to market competing

With respect to the finding of literal infringement, Hospira argued that it cannot literally infringe the claims of the ’209 patent because intravenous administration of pemetrexed ditromethamine dissolved in saline—a solution which contains pemetrexed and chloride anions alongside sodium and tromethamine cations—is not “administration of pemetrexed disodium.” The Federal Circuit agreed, finding that “[i]t was clearly erroneous for the district court to hold that the ‘administration of pemetrexed disodium’ step was met because Hospira’s pemetrexed ditromethamine product will be dissolved in saline before administration. A solution of pemetrexed and chloride anions and tromethamine and sodium cations can-not be deemed pemetrexed disodium simply because some assortment of the ions in the solution consists of pemetrexed and two sodium cations.” The Federal Circuit concluded that to literally practice the “administration of pemetrexed disodium” step under the district court’s claim construction, the pemetrexed disodium salt must be itself administered.

With respect to the Doctrine of Equivalaents, the main dispute was whether prosecution history estoppel prevented Lilly from claiming that the administration of pemetrexed ditromethamine was an infringing equivalent to administering pemetrexed disodium. During prosecution, Lilly amended the claims from “an antifolate” to “pemetrexed disodium.” Lilly conceded that this was a narrowing amendment, and that it was made for reasons of patentability. However, Lilly argued that the rationale of its amendment bore “no more than a tangential relation to the equivalent in question.”

Lilly argued that the district court properly held that the reason for its amendment was to distinguish pemetrexed from antifolates generally and that the different salt type is a merely tangential change with no consequence for pemetrexed’s administration or mechanism of action within the body. The Federal Circuit agreed with Lilly. Noting that “tangential” meant “touching lightly or in the most tenuous way,” the Federal Circuit said that the reason for the amendment was to distinguish methotrexate. Under these circumstances the particular type of salt to which pemetrexed is complexed relates only tenuously to the reason for the narrowing amendment, which was to avoid methotrexate . The Federal Circuit therefore held that Lilly’s amendment was merely tangential to pemetrexed ditromethamine because the prosecution history, in view of the ’209 patent itself, strongly indicates that the reason for the amendment was not to cede other, functionally identical, pemetrexed salts.

The Federal Circuit also found support in the prosecution record, noting that Lilly’s amendment, inartful though it might have been, was prudential in nature and did not need or intend to cede other pemetrexed salts. Because the references specifically mentioned pemetrexed the Federal Circuit saiad that narrowing “antifolate” to “pemetrexed disodium” could not possibly distinguish the art cited in the obviousness ground of rejection.

Lilly’s burden under Festo was to show that pemetrexed ditromethamine was “peripheral, or not directly relevant,” to its amendment, and the Federal Circuit concluded it had done so.

The Federal Circuit also rejected arguments that the disclosure-dedication rule prevented a finding of infringement under the docitrine of equivavlents, agreeing with Lilly that the ’209 patent does not disclose methods of treatment using pemetrexed ditromethamine, and, as a result, Lilly could not have dedicated such a method to the public.

Because neither prosecution history estoppel nor the disclosure-dedication rule bars Lilly from asserting infringement through equivalence, the Federal Circuit affirmed the judgement of infringement.