in Nobel Biocare Services AG v. Instradent USA, Inc., [2017-2256] (September 13, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s determination that claims 1-5 and 19 of U. S. Patent No. 8,714,977,directed to dental implants, were anticipated.

The undisputed critical date of the ‘977 patent was May 23, 2003, and Instradent alleged that the claims were anticipated by an ABT “Product Catalog” with the date

“March 2003” on the cover. The ITC, applying a clear and convincing evidentiary standard, had previously determined that the claims were not anticipated, and the Federal Circuit affirmed.

Meanwhile, Instradent petitioned for IPR. While the Board adopted the same claim construction as the ITC, and considered the same evidence presented to the ITC, the Board also considered new evidence not considered by the ITC, including the declarations and deposition testimony of Hantman and Chakir that the catalog was available to the industry in March 2003. The Board determined that a preponderance of the evidence establishes that the ABT Catalog qualifies as a prior art printed publication under 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

On appeal, the parties disputed whether the ABT Catalog qualifies

as a “printed publication” under § 102(b). The Federal Circuit said that whether a reference qualifies as a “printed publication” is a legal conclusion based on underlying factual findings, including The parties dispute whether the ABT Catalog qualifies

as a “printed publication” under pre-AIA § 102(b). Whether a reference qualifies as a “printed publication” is a legal conclusion based on underlying factual findings, including whether a reference was publicly accessible. Public accessibility has been called the touchstone in determining whether a reference constitutes a “printed publication.” A reference will be considered publicly accessible if it was disseminated or otherwise made available to the extent that persons interested and ordinarily skilled in the subject matter or art exercising reasonable diligence can locate it.

The Federal Circuit noted that it was not bound by its prior affirmance of the ITC’s holding that there was insufficient evidence to find pre-critical date public accessibility, observing that the evidentiary standard in IPRs, “preponderance of the evidence” is different from the higher standard applicable in ITC proceedings. The Federal Circuit further noted that the Board also had more evidence on this issue than what was before the ITC. Finally the Federal Circuit said that under the substantial evidence standard, the inconsistent conclusions from the evidence does not prevent an administrative agency’s finding from being supported by substantial evidence.

The Federal Circuit agreed with Instradent that substantial evidence supported the Board’s finding that the ABT Catalog was publicly accessible prior to the critical date. The Board credited Chakir and Hantman’s testimony that Chakir obtained a copy of the ABT Catalog at the March 2003 IDS Conference and that Hantman retained that copy in

his records thereafter. Furthermore, Hantman’s declaration included excerpts of his copy of the ABT Catalog taken from his files. The Board found that Hantman’s copy of the ABT Catalog and the copy offered as prior art by Instradent in the IPR had identical pages except for some handwriting on the cover of Hantman’s copy.

The Federal Circuit noted that corroboration is required of any witness whose testimony alone is asserted to invalidate a patent, regardless of his or her level of interest. Corroborating evidence may include documentary or testimonial evidence, and circumstantial evidence can be sufficient corroboration. The Federal Circuit listed eight factors to be considered in evaluating corroboration:

(1) the relationship between the corroborating witness and the alleged prior user,

(2) the time period between the event and trial,

(3) the interest of the corroborating witness in the subject matter in suit,

(4) contradiction or impeachment of the witness’ testimony,

(5) the extent and details of the corroborating testimony,

(6) the witness’ familiarity with the subject matter of the patented invention and the prior use,

(7) probability that a prior use could occur considering the state of the art at the time,

(8) impact of the invention on the industry, and the commercial value of its practice.

Applying a “rule of reason” analysis to the corroboration requirement, which “involves an assessment of the totality of the circumstances including an evaluation of all pertinent evidence, the Federal Circuit held the corroboration to be sufficient, noting “there are no hard and fast rules as to what constitutes sufficient corroboration, and each case must be decided on its own facts.”

The Federal Circuit rejected the challenges to the claim construction, and affirmed the Board.

where the Supreme Court invalidated U.S. Patent No. 3,223,070, entitled “Dairy Establishment,” covering a water flush system to remove cow manure from the floor of a dairy barn, citing the Legends of Hercules from Witt, Classic Mythology (1883). The Supreme Court noted in a footnote that Heracles cleansed the stables of Augeas, King of Elis, in a single day.

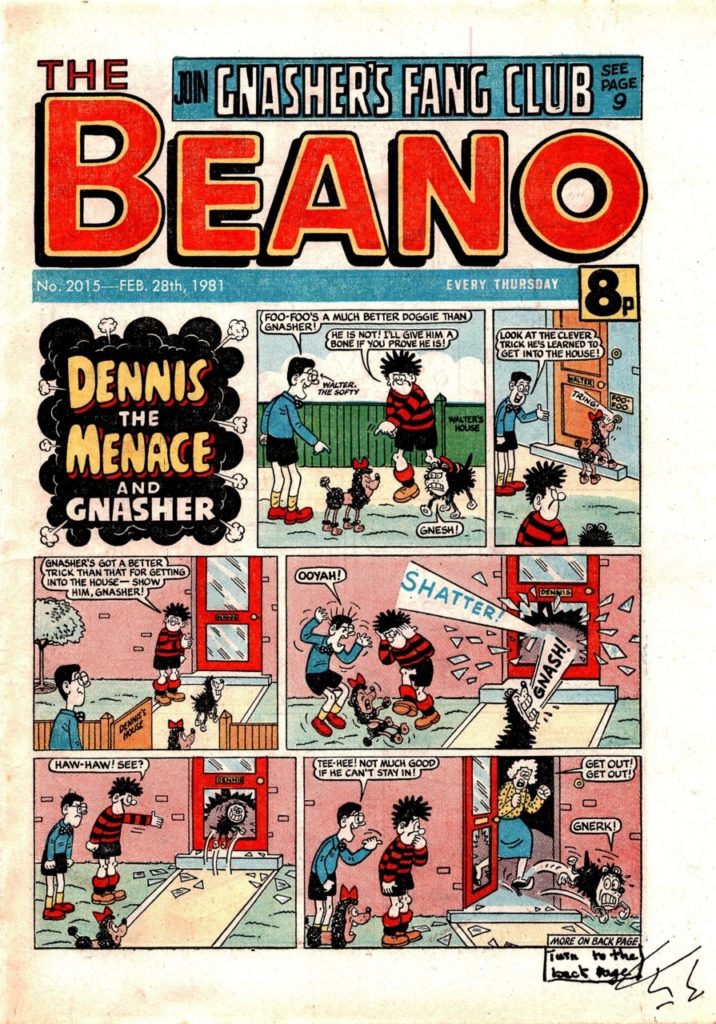

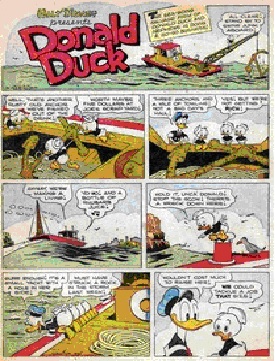

where the Supreme Court invalidated U.S. Patent No. 3,223,070, entitled “Dairy Establishment,” covering a water flush system to remove cow manure from the floor of a dairy barn, citing the Legends of Hercules from Witt, Classic Mythology (1883). The Supreme Court noted in a footnote that Heracles cleansed the stables of Augeas, King of Elis, in a single day. of Raising Sunken or Stranded Vessels. Mr. Kroyer successfully raised the sunken freighter Al Kuwaita from the bottom of Kuwait harbor by pumping 27 million expanded polystyrene balls to raise the sunken freighter. He then filed patent applications in Denmark, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. Things were going well until the Netherlands patent examiner found a Donald Duck cartoon in which Huey, Dewey, and Louie helped to raise Scrooge McDuck’s yacht by filling it with ping pong balls.

of Raising Sunken or Stranded Vessels. Mr. Kroyer successfully raised the sunken freighter Al Kuwaita from the bottom of Kuwait harbor by pumping 27 million expanded polystyrene balls to raise the sunken freighter. He then filed patent applications in Denmark, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. Things were going well until the Netherlands patent examiner found a Donald Duck cartoon in which Huey, Dewey, and Louie helped to raise Scrooge McDuck’s yacht by filling it with ping pong balls.