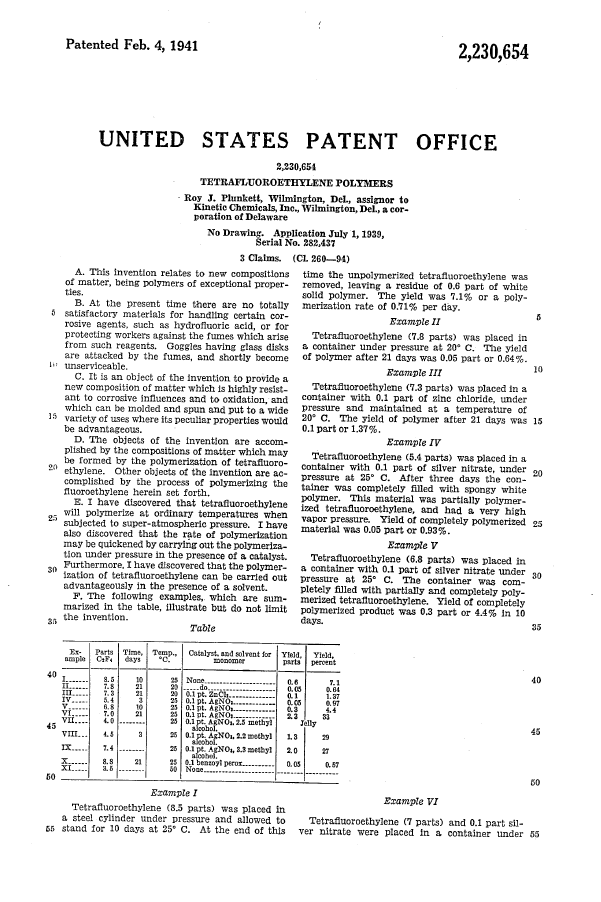

On February 4, 1941, Roy J. Plunkett received U.S. Patent No. 2,230,654, on Tetrafluoroethylene, assigned to his employer Kinetic Chemicals, Inc.:

Plunkett had earned a PhD in chemistry, but his discovery of Teflon was largely by accident. Plunkett was working in a laboratory in Edison, New Jersey, in 1938 trying to find alternative chlorofluorocarbon refrigerants. He and his assistant made about 100 pounds of Tetrafluoroethylene (TFE), a common precursor of refrigerants. They froze the TFE in a gas cylinder, but the next day no gas came out. They opened the cylinder and found that the TFE had polymerized into a white powdery substance.

Plunket studied the powdery substance further and found its properties to be waxy, very slippery, chemically stable and had a high melting point. DuPont went to work on the new polymer, and by 1941 it had found numerous applications, and given a new name -Teflon.

Teflon became so well known for its slipperiness, that it found use in in common parlance, President Ronald Reagan being dubbed the “Teflon President,” and John Gotti, being called the “Teflon Don.”