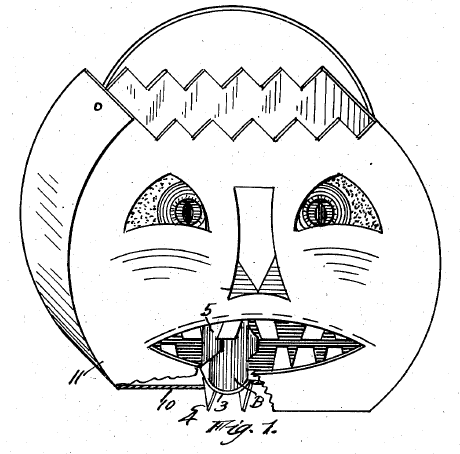

What’s scarier than a Section 101 rejection? Some of these patents for celebrating the spookiest holiday?

Monthly Archives: October 2021

IPR’s Survive More Constitutional Challenges

In Mobility Workx, LLC v. Unified Patents, LLC, [2020-1441] (October 13, 2021), the Federal Circuit concluded that Mobility’s constitutional arguments were without merit, and without reaching the merits of the Board’s decision, in light of Arthrex, it remanded to the Acting Director to determine whether to grant rehearing.

Mobility argued that the structure and funding of the Board violates due process. First, because “the fee-generating structure of AIA review[] creates a temptation” for the Board to institute AIA proceedings in order to collect post institution fees (fees for the merits stage of the AIA proceedings) and fund the agency. Second, because individual APJs have an unconstitutional interest in instituting AIA proceedings because their own compensation in the form of performance bonuses is favorably affected. The Federal Circuit found no merit to these defenses.

Mobility raised several additional constitutional challenges not raised before the agency that have been previously rejected by this court in other cases. Mobility argued that the Director’s delegation of his authority to institute AIA proceedings violates due process and the Administrative Procedure Act because the Director has delegated the initial institution decision to “the exact same panel of Judges that ultimately hears the case.” Mobility additionally argued that subjecting a pre-AIA patent to AIA review proceedings “constitutes an unlawful taking of property.” The Federal Circuit rejected these challenges.

Finally, Mobility raised an Appointments Clause challenge. The Federal Circuit agreed that a remand is required under the Supreme Court’s decision in Arthrex to allow the Acting Director to review the final written decision of the APJ panel pursuant to newly established USPTO procedures, and remanded the case.

An Army of Citation Footnotes Crouching in a Field of Jargon is no Substitute Explanation

In Traxcell Technologies, LLC v. Sprint Communications Company, LP, [2020-1852, 2020-1854] (October 12, 2021), the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, and further that under that construction Traxcell failed to show a genuine issue of material fact as to infringement, and further that several of Traxcell’s claims were indefinite.

The case involves U.S. Patent Nos. 8,977,284, 9,510,320, 9,642,024, and 9,549,388 related to self-optimizing network technology for making “corrective actions” to improve communications between a wireless device and a network.

At issue was the claim limitation “means for receiving said performance data and corresponding locations from said radio tower and correcting radio frequency signals of said radio tower.” The parties agreed that this was a means-plus-function claim, and the corresponding structure was an algorithm identified in the specification. Traxcell argued that Sprint’s accused technology included a structural equivalent to the disclosed structure under the function-way-result test. The district court disagreed, reasoning that Traxcell failed to establish that Sprint’s accused technology operates in substantially the same “way.”

The Federal Circuit agreed, noting that the identified structure from the specification was a “very detailed” algorithm, including numerous steps necessary for its function. However, Traxcell neglected to address a significant fraction of that structure. Accordingly, Traxcell didn’t provide enough evidence for a reasonable jury to conclude that the accused structure performs the claimed function in “substantially the same way” as the disclosed structure.

Also at issue was the limitation “location.” The parties agreed, and the district court accepted, that “location” meant “location that is not merely a position in a grid pattern.” However, under this construction Traxell lost. On appeal Traxell insisted in retrospect that this construction was wrong. The Federal Circuit said that “having stipulated to it, Traxcell cannot pull an about-face.”

With respect to infringement by Sprint, the independent claims all require sending, receiving, generating, storing, or using the “location” of a wireless device. The district court concluded that Traxcell simply hadn’t shown that the accused technologies used “location” as construed by the court, and the Federal Circuit agreed. With respect to infringement by Ericson, the district court rejected Traxcell’s argument that the accused technology uses “location” because it collects “information regarding the distance of devices from a base station.” The Federal Circuit agreed that this was not location information but information to calculate distance.

Also at issue were the limitations “first computer” and “computer.” Construing these as referring to a single computer, the district court concluded that Traxell had not shown that these limitations were met, and the Federal Circuit agreed. The Federal Circuit said that Traxell failed to particularize those conclusory assertions with specific evidence and arguments. Traxell argued it provided substantial evidence that the district court ignored, but the Federal Circuit said it was “an army of citation footnotes crouching in a field of jargon. What they lack is explanation.” The Federal Circuit concluded that Traxell’s showing was “simply too unexplained and conclusory.” The Federal Circuit said that Traxcell has cited swaths of documents, but it Failed to explain how those documents support its infringement theory. It didn’t do so at the trial court, and it didn’t do so on appeal.

Traxcell’s remaining infringement arguments on appeal relied upon the doctrine of equivalents. But the Federal Circuit concluded that Traxcell surrendered multiple computer equivalents during prosecution of these patents.

Turning to indefiniteness, Claim 1 of the ‘284 patent was found indefinite on two grounds: (1) lack of reasonable certainty about which “wireless device” the term “at least one said wireless device” referred to, and (2) lack of an adequate supporting structure in the specification for the claim’s means-plus-function limitation. The Federal Circuit found that the claim was indefinite for lack of adequate supporting structure in the specification.

A means-plus-function claim is indefinite if the specification fails to disclose adequate corresponding structure to perform the claimed function. While Traxcell cited an algorithm, the district court found that Traxcell’s explanation provided nothing more than a restatement of the function, as recited in the claim. The Federal Circuit concluded that the claim was indefinite, without the need to reach the issue of “wireless device.”

As to infringement of the ‘388 patent, the claims required that the device’s location is (1) determined on the network, (2) communicated to the device, and (3) used to display navigation information. The district court determined that Traxcell failed to show that the device location was determined by the network, and the Federal Circuit agreed. Traxcell argued that the network provided data to the devices, but the court observed that it is not data from the network that the claims require. It is that the network itself determines location and transmits the location to the device. The Federal Circuit said that Traxcell has not shown that the network does so with anything but broad and conclusory scattershot assertions.

Revised Judgment is Less Judgmental

In Hyatt v. Hirshfeld, [2020-2321, 2020-2323, 2020-2324, 2020-2325] (October 12, 2021), the Federal Circuit reissued its August 18, 2021, opinion, at Hyatt’s request, striking the language “in an efforts to submarines his patent applications and receive lengthy patent terms,” leaving the much less judgmental observation that Hyatt “adopted an approach to prosecution that all but guaranteed indefinite prosecution delay.”

A Little Background on Columbus

First, a little background on Backgrounds. 37 CFR 1.77(b)(7) suggests that an application should contain a “background of the invention.” However the MPEP is ambiguous as to its content:

Experienced practitioners know that the Background is just another opportunity to make a mistake. From calling it a “BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION” rather than simply “BACKGROUND,” to admitting admitting prior art that is not prior art, or otherwise limiting the scope of the claims, ther seems little to be gained and much to be lost with a carelessly drafted background. While patent applications continue to include Backgrounds, they are getting shorter and less detailed.

An interesting example of an old-school background, particularly apropos on Columbus Day, is the Background in U.S. Patent No. 5,802,513:

The drafter probably should have stopped right here, and today probably would have stopped right here. A hint about the subject matter of the invention, and the problems it addresses, without admitting anything in particulary is prior are, and without saying anything that might otherwise limit the scope of the claims.

THIS forum selection clause in THIS NDA agreement did not bar the IPRs

In Kannuu Pty Ltd. v. Samsung Electronics Co., [2021-1638] (October 7, 2021) the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court denial of Samsung’s motion for a preliminary injunction compelling Samsung to seek dismissal of Samsung’s petitions for inter partes review at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (Board).

In 2012, Samsung contacted Kannuu, an Australian start-up company that develops various media-related products (including Smart TVs and Blu-ray players), inquiring about Kannuu’s

remote control search-and-navigation technology. Kannuu and Samsung entered into a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), to protect confidential business information while engaging in business discussions and the like. Among other things, the agreement provided:

Any legal action, suit, or proceeding arising out of or relating to this Agreement or the transactions contemplated hereby must be instituted exclusively in a court of competent jurisdiction, federal or state, located within the Borough of Manhattan, City of New

York, State of New York and in no other jurisdiction.

Following over a year of discussions, the parties ceased communications. No deal (i.e., intellectual property license, purchase, or similar agreement) over Kannuu’s technology was made. Six years later, Kannuu sued Samsung for patent infringement and breach of the NDA.

Samsung then filed petitions for inter partes review of the patents. Kannuu argued that the that review should not be instituted because Samsung violated the NDA’s forum selection

clause in filing for such review. When the Board institued proceedings as to some of the petitions, Kannuu sought rehearing, which was denied. Kannuu then sought a preliminary injunction to compel Samsung to seek dismissal of the instituted inter partes reviews. The

motion was denied, and Kannuu appealed.

The issue before the district court, and before the Federal Circuit on appeal, was whether the forum selection in the non-disclosure agreement prohibited Samsung from petitioning for inter partes review of Kannuu’s patents at the Board. The District Court found it did not, and the Federal Circuit found no abuse of discretion.

Though the district court held the forum selection clause was valid and enforceable, it concluded that the plain meaning of the forum selection clause in the NDA did not encompass the inter partes review proceedings. Specifically, the district court found that the inter partes review proceedings did not “relate” to the Agreement or transactions contemplated under it. The Federal Circuit said that the district court correctly concluded that the inter partes review proceedings “do not relate to the Agreement itself.” The connection between the two—the inter partes review proceedings and the NDA—is too tenuous for the inter partes review proceedings to be precluded by the forum selection clause in the NDA, which is a contract

directed to maintaining the confidentiality of certain disclosed information, and not related to patent rights.

Neither the district court nor the Federal Circuit said that a forum selection clause in an NDA could not bar an IPR, rather they both held that this forum selection clause in this NDA agreement did not bar the IPRs. Under appropriate circumstances, a properly drafted forum selection cause in an NDA could bar an IPR between the parties, just as such clauses in a license agreement can bar challenges to the licensed patents before the PTAB.

What’s in a Name? Patentability.

In re SurgiSil LLP, [2020-1940] (October 4, 2021), the Federal Circuit reversed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision affirming an examiner’s rejection of SurgiSil’s design patent application, No. 29/491,550 an “ornamental design for a lip implant as shown and described.”

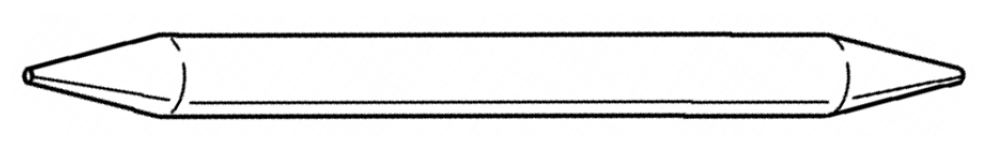

The examiner rejected the sole claim of the application as anticipated by an art tool called a stump, shown in a Dick Blick catalog (Blick):

.

The Board rejected SurgiSil’s argument that Blick could not anticipate because it disclosed a “very different” article of manufacture than a lip implant, reasoning that it is appropriate to ignore the identification of the article of manufacture in the claim language, because whether a reference is analogous art is irrelevant to whether that reference anticipates.

The Federal Circuit said that a design claim is limited to the article of manufacture

identified in the claim; it does not broadly cover a design in the abstract. The Federal Circuit noted that in Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2019), it held that the design patent was limited to the particular article of manufacture

identified in the claim, i.e., a chair, and not other furniture.

The Federal Circuit noted that the claim identified a lip implant, and the Board found

that the application’s figure depicts a lip implant. As such, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other articles of manufacture. There is no dispute that Blick discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, so the Board’s anticipation finding therefore rested on an erroneous interpretation of the claim’s scope. Thus the Federal Circuit reversed the rejection of the claim.

As a result, a carefully selected title may allow a designer to get a patent where the design is similar to the designs for other types of protects. What’s in a name? Patentability.

Providing Software Does Not Make the Provider the “Final Assembler”

In Acceleration Bay LLC v. 2K Sports, Inc., [2020-1700] (October 4, 2021), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction of U.S. Patent No. 6,910,069 and its grant of summary judgment of non-infringement as to the ’069 and U.S. Patent No. 6,920,497, and dismissed the appeal of non-infringement U.S. Patent Nos. 6,701,344 , 6,714,966

With respect to the ‘069 patent, Acceleration Bay argued that the district court erroneously interpreted the claim term “fully connected portal computer” to include a “m-regular” limitation, i.e., a requirement that each participant in the network is connected to exactly m neighbor participants. Take Two argued that pointed out that the district court did not only construe the term “fully connected portal computer” to include the M-regular limitation, but it also construed the term “each participant being connected to three or more other participants” to include it. Since Acceleration Bay did not challenge the construction of each participant being connected to three or more other participants, Take Two argued that the appeal should fail, and the Federal Circuit agreed.

With respect to the ‘497 patent, the Federal Circuit said that Acceleration Bay proffered a “novel theory, without case law support,” that the defendants are liable for “making” the

claimed hardware components, even though they are in fact made by third parties, because defendant’s accused software runs on them, the customer, not Take Two, completes the system by providing the hardware component and installing Take Two’s software. Thus the “final assembler” doctrine of Centrak (where the accused infringer made hardware products and installed them by connecting them to an existing network to create an infringing system) did not apply.