In Inline Plastics Corp. v. Lacerta Group, LLC, [2022-1954, 2022-2295] (Fed. Cir. 2024), the Federal Circuit affirmed the judgment of non-infringement, but vacated the jury determination of invalidity because of an error in jury instructions on the objective indicia of nonobviousness.

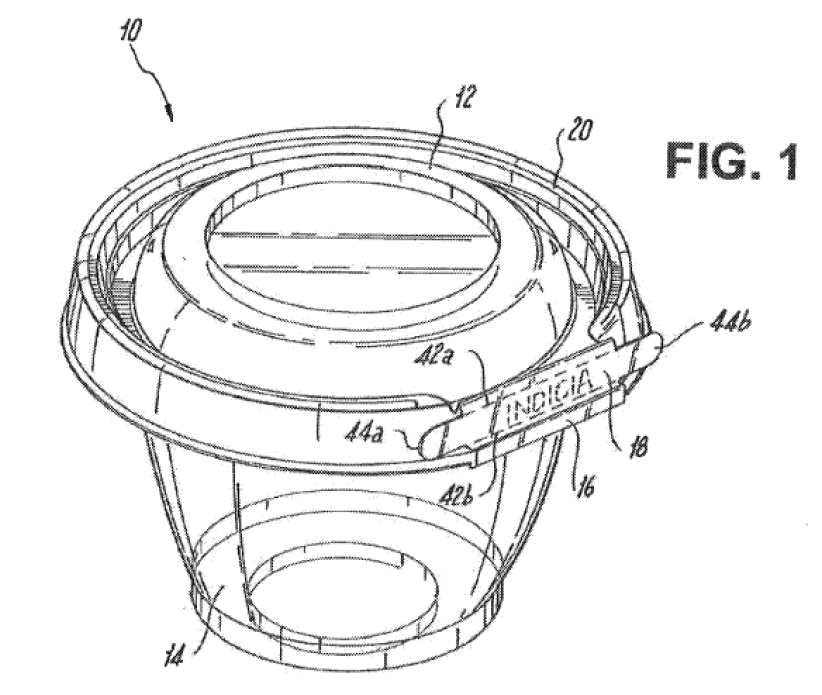

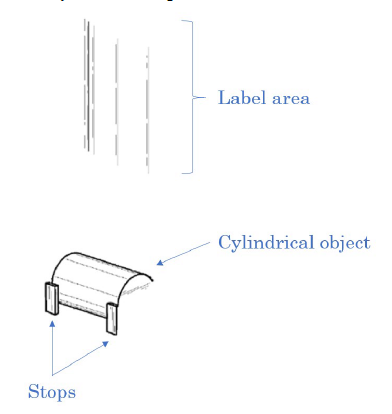

The case involved U.S. Patent Nos. 7,118,003; 7,073,680; 9,630,756; 8,795,580; and 9,527,640, which describe and claim tamper resistant and tamper evident containers,

On the invalidity issue, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument that the references were “cumulative” of PTO-considered references, pointing out that Inline cites no authority that

precludes a successful obviousness challenge that rests on PTO-considered references.

The Federal Circuit also rejected the argument that there was no legally sufficient evidence of the motivation to combine references. The Federal Circuit said that it has consistently stated that a court or examiner may find a motivation to combine prior art references

in the nature of the problem to be solved” and that “[t]his form of motivation to combine evidence is particularly relevant with simpler mechanical technologies. Further, the Federal Circuit it has recognized that some cases involve technologies and prior art that are simple enough that no expert testimony is needed” regarding a motivation to combine.

Finally, the Federal Circuit rejected Inline’s argument that Lacerta’s challenge must fail because it did not rebut or even address Inline’s objective- indicia evidence. The Court said that is has never held that the challenger must present its own testimony on objective indicia or else the patentee’s evidence must be credited, much less must be credited as dispositive of the obviousness issue.

As to the jury instruction on objective-indicia, the Federal Circuit agreed that the instruction was legal error. The Federal Circuit noted that Inline presented evidence of industry praise for its products, as well as evidence for additional objective indicia, such as copying and licensing. The Court said that this evidence, taken together, called for an instruction, if properly requested, on the objective indicia to which the evidence pertains, so that the jury

could assess its weight as objective indicia and—where the jury was asked for the bottom-line answer on obviousness— in relation to the prima facie case. However, the district court

did not give such an instruction.

The error in the objective-indicia instruction here was not harmless (whether under Federal Circuit or First Circuit law). We cannot say that a proper instruction would have made no difference to a reasonable jury regarding invalidity.