In Sionyx, LLC, v. Hamamatsu Photonics KK, [2019-2359, 2020-1217] (December 7, 2020), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s judgment that (1) Hamamatsu breached its Non-Disclosure Agreement SiOnyx”; (2) Hamamatsu willfully infringed U.S. Patent 8,080,467; (3) SiOnyx is entitled to $796,469 in damages and $1,091,481 of pre-judgment interest for breach of the NDA; (4) SiOnyx is entitled to $580,640 in damages and $660,536 of pre-judgment interest for unjust enrichment; (5) SiOnyx is entitled to post-judgment interest at the statutory rate for its breach of contract and unjust enrichment claims; (6) Dr. James Carey is a co-inventor of U.S. Patents 9,614,109; 9,293,499; 9,190,551; 8,994,135; 8,916,945; 8,884,226; 8,742,528; 8,629,485; and 8,564,087; (7) SiOnyx is entitled to sole ownership of the Disputed U.S. Patents; (8) SiOnyx is entitled to an injunction prohibiting Hamamatsu from practicing the Disputed U.S. Patents for breach of the NDA; and (9) SiOnyx is entitled to an injunction prohibiting Hamamatsu from practicing the ’467 patent for infringement; and rreversed the district court’s denial of SiOnyx’s motion to compel Hamamatsu to transfer ownership of the corresponding foreign patents to SiOnyx.

Eric Mazur discovered a process for creating “black silicon” by irradiating a silicon surface with ultra-short laser pulses. In addition to turning the silicon black, the process creates a textured surface, and the resulting black silicon has electronic properties different from traditional silicon. After discovering the process for making the material, Mazur worked with his students, including Carey, to study its properties and potential uses. Based on this work, Mazur and Carey filed patent applications which resulted in the issuance of several patents, including U.S. Patent No. 8,080,467.

Mazur and Carey founded SiOnyx to further develop and commercialize black silicon. SiOnyx met with Hamamatsu, a producer of silicon-based photodetector devices, enteringg an NDA to allow the parties to share confidential information relating to “evaluating applications and development opportunities of pulsed laser process doped photonic devices.

After the NDA was terminated, Hamamatsu continued to develop new photodetector devices, filing patent applications and introducing products,. SiOnyx met with Hamamatsu to discuss ownership of the disputed U.S. and Foreign patents, but the parties did not reach an agreement, so SiOnyx sued Hamamatsu claiming (1) breach of contract; (2) unjust enrichment; (3) infringement of the ’467 patent; and (4) change of inventorship of the Disputed U.S. Patents.

After a jury verdict in SiOnyx’s favor, Hamamatsu appealed. Hamamatsu first argued that the claim was barred by the statute of limitations, which Hamamatsu argued was triggered by its failure to return confindential information as required by the NDA, and by Hamamatsu emailing SiOnyx a diagram of a photodiode that SiOnyx perceived to be identical to the parties’ 2007 work. SiOnyx argued that Hamamatsu’s failure to return SiOnyx’s confidential information was an immaterial breach that did not begin the limitations period, or that Hamamatsu concealed its later use of SiOnyx’s confidential information through its repeated assurances that its new products did not infringe SiOnyx’s intellectual property. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that a reasonable juror could have determined that SiOnyx was not harmed by Hamamatsu’s failure to return the confidential information and that the breach was therefore immaterial and did not cause SiOnyx’s claims to accrue, as to the email disclosures, the Federal Circuit perceived no reason to upset the jury’s verdict here.

Hamamatsu also argued that the district court erred in awarding pre-judgment interest for unjust enrichment and breach of contract claims. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that pre-judgment interest was avaialble for both claims.

Hamamatsu challenged the injunction against infringement of SiOnyx’s ‘467 patent, arguing that SiOnyx argues primarily that SiOnyx failed to demonstrate irreparable harm and an inadequate remedy at law. SiOnyx responded that its products compete with Hamamatsu’s, and that it will suffer irreparable harm from Hamamatsu’s continued sales. The Federal Circuit was not convinced that the district court clearly erred in finding that the accused products are competitive with SiOnyx’s products, and Hamamatsu did not refute the demonstration of irreparable harm.

Hamamatsu also challenged the injunction for breach of contract. However, due to the similarity of the legal standard, the parties’ arguments were substantially similar to those made with respect to the injunction for patent infringement, and the Federal Circuit reached the same conclusion.

Hamamatsu filed a post-trial motion for judgment as a matter of law that SiOnyx is not owed damages for the breach of contract and unjust enrichment claims after the confidentiality period of the NDA expired. SiOnyx responded that the jury reasonably could have inferred that Hamamatsu continued to benefit from its breach beyond the expiration of the confidentiality period. The Federal Circuit agreed that the jury’s verdict could be reasonably construed to incorporate a finding that Hamamatsu continued to reap the benefit of their earlier breach by selling products that it had designed using SiOnyx’s confidential information, and declined .” Id. slip op. at 3. We agree that such an inference is reasonable, and we de-cline to alter the jury’s damages award.

On appeal, Hamamatsu argues that the district court erred in granting SiOnyx sole ownership of the disputed U.S. Patents because the jury’s finding of co-inventorship necessarily implied that the jury found that Hamamatsu also contributed to the patents. The NDA provided that “a party receiving confidential information acknowledges that the disclosing party claims ownership of the information and all patent rights “in, or arising from” the information.” Thus the Federal Circuit found that the district court’s decision transferring ownership of the patents according to the terms of the NDA was an equitable remedy which is reviewed for abuse of discretion (under Massachusetts law). The Federal Circuit said that absent evidence that Hamamatsu contributed confidential information to the patents under the NDA, it was not entitled to co-ownership of the patents under the agreement.

On appeal, Hamamatsu maintained that its infringement was not willful, challenging the adequacy of the evidence presented at trial to support the jury’s finding. However, the Federal Circuit said that given that the district court awarded no enhanced damages based on willfulness, it is not apparent what effect the jury’s finding of willfulness had on the district court’s judgment, and it is likewise not apparent what the effect a reversal by this court would be. Hamamatsu was in effect requesting an advisory opinion, which the Federal Circuit lacks the authority to provide.

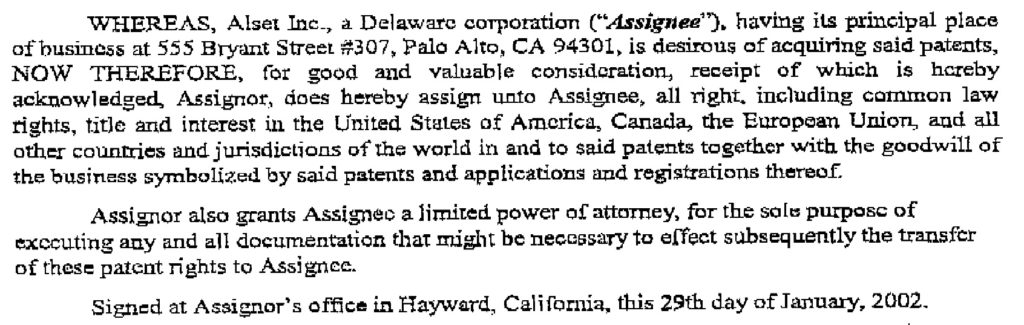

On SiOnyx’s cross appeal, SiOnyx aruged that the district court should have granted it ownership of the corresponding foreign patents as well. The Federal Circuit agree with SiOnyx that the evidence that established SiOnyx’s right to sole ownership of the disputed U.S. Patents also applied to the disputed foreign patents. Because the district court erroneously perceived that it lacked authority to compel the transfer of ownership, the Federal Circuit said it was an abuse of discretion to distinguish between the two groups of patents. The Federal Circuit stated that the district court had authority to transfer foreign patents owned by the parties before it.