In B/E Aerospace, Inc. v. C&D Zodiac, Inc., [2019-1935, 2019-1936] (June 26, 2020), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s determination that the challenged claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 9,073,641 and 9,440,742 relating to aircraft lavatories, were not valid for obviousness.

The Federal Circuit tipped its hand early in the opinion, declaring “The technology involved in this appeal is simple” — not a good sign in an obviousness case.

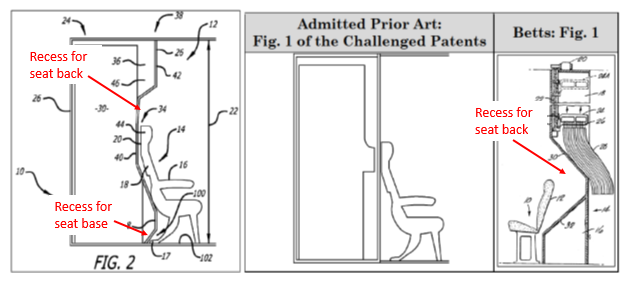

The invention related to maximizing the space in an aircraft lavatory while accommodating passenger seats, by providing recesses for the seat back and for the seat base.

The Federal Circuit said there was no dispute that Betts’s contoured wall design meets the “first recess” claim limitation. Nor do the parties dispute that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to modify the Admitted Prior Art with Betts’s contoured wall because skilled artisans were interested in maximizing space in airplane cabins. The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s conclusion that the challenged claims would have been obvious because modifying the Admitted Prior Art/Betts combination to include a second recess for the seat base was nothing more than the predictable application of known technology: a person of skill in the art would have applied a variation of the first recess and would have seen the benefit of doing so.

The Federal Circuit also affirmed the Board’s conclusion that the challenged claims would have been obvious because “it would have been a matter of common sense” to incorporate a second recess in the Admitted Prior Art/Betts combination.

While B/E asserted that the Board legally erred by relying on “an unsupported assertion of common sense” to “fill a hole in the evidence formed by a missing limitation in the prior art,” the Federal Circuit disagreed:

In KSR, the Supreme Court opined that common sense serves a critical role in determining obviousness. 550 U.S. at 421. As the Court explained, common sense teaches that familiar items may have obvious uses beyond their primary purposes, and in many cases a person of ordinary skill will be able to fit the teachings of multiple patents together like pieces of a puzzle.