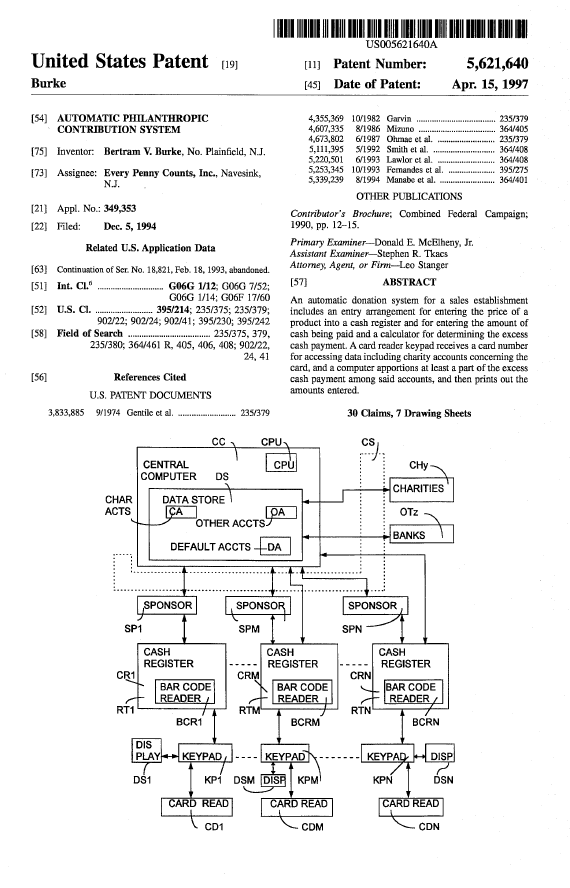

On April 15, 1997, U.S. Patent No. 5,621,640, issued to Bertram V. Burke on an Automatic Philanthropic Contribution System:

This was the first of four patents on the idea of rounding up a purchase and contributing the add-on to one or more charities. The others U.S. Patent No. 6,088,682, 6,876,976, and 7171270. They were all assigned to Every Penny Counts, which unsuccessfully tried to assert them against various banks and credit card companies. See, Every Penny Counts, Inc. v. Am. Express Co., 563 F.3d 1378, 90 U.S.P.Q.2d 1851 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

Bertram Burke was a retired psychoanalyst who related his “invention” back to an experience he had buying ice cream: after he paid for an ice cream cone, he was given 52 cents in change and he thought that this small amount of change was practically worthless. He considered putting the change in a canister on the counter ostensibly intended to raise money for a charitable cause, but he did not trust that the money in the canister would actually be devoted to charity. He describes his invention as a way of solving this “problem of loose change.”

The big question on Tax Day is how do you deduct these microdonations?