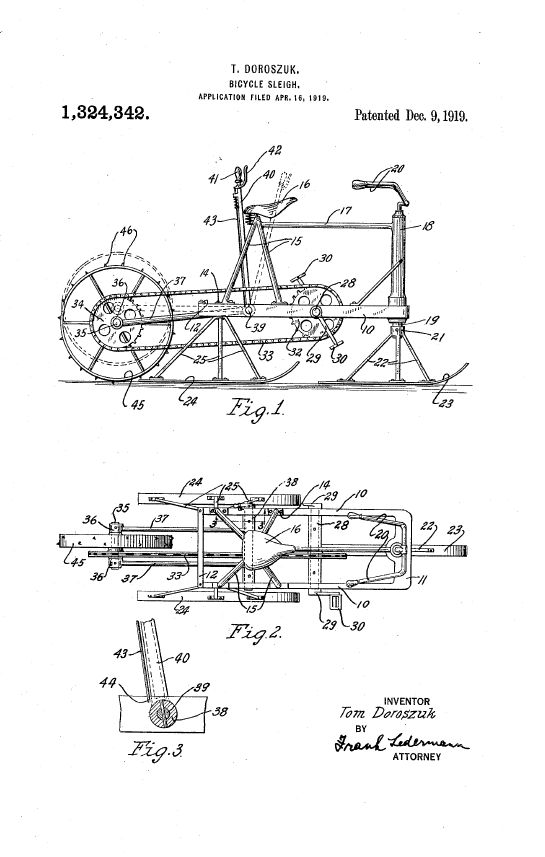

On December 9, 1919, Tom Doroszuk received U.S. Patent No. 1,324,342 on a Bicycle Sleigh:

According to the patent, its object is “the provision of a vehicle simulative of a bicycle and similarly operated ·whereby a rider may advance over the surface of ice or snow at a relatively high speed.”

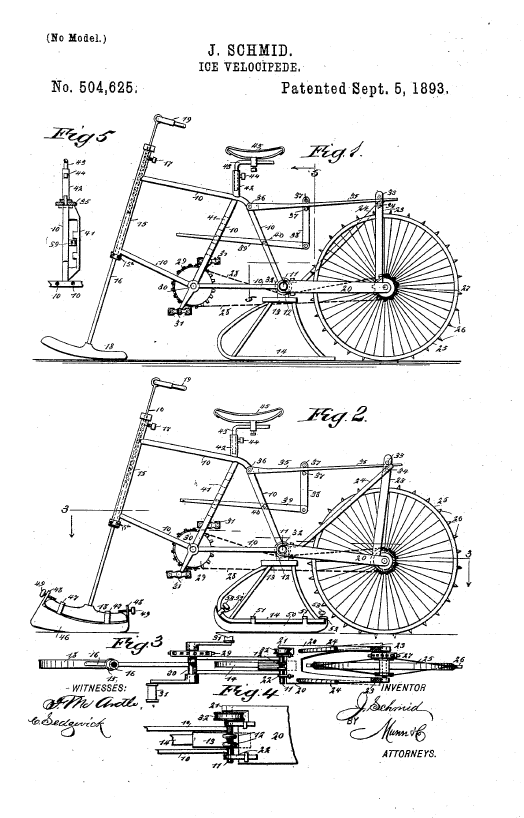

There were earlier patents on winterized bicycles, including U.S. Patent No. 504,625 on an Ice Velocipede:

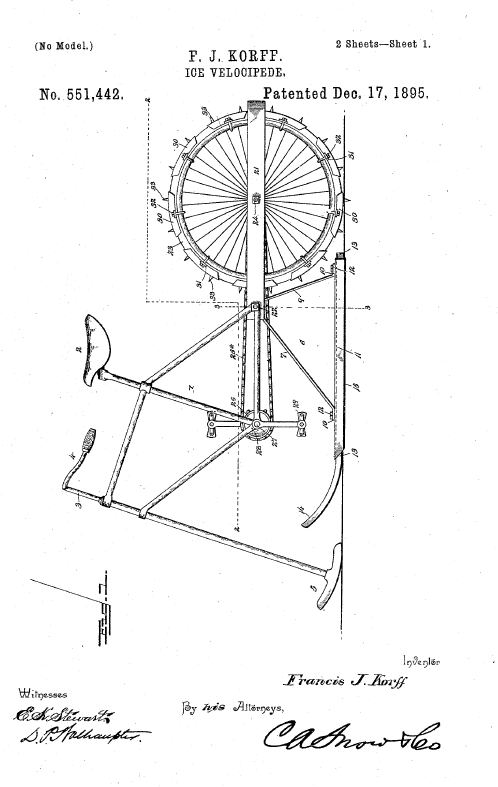

U.S. Patent No. 551442 on an Ice Velocipede:

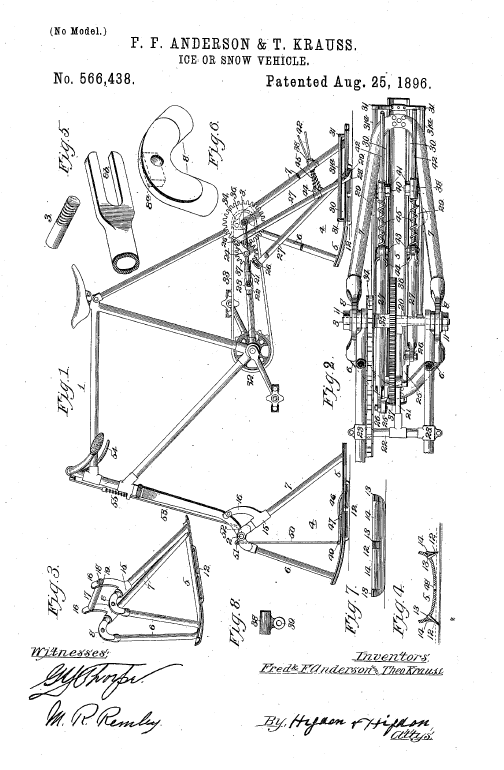

U.S. Patent No. 566,483 on Ice or Snow Vehicle:

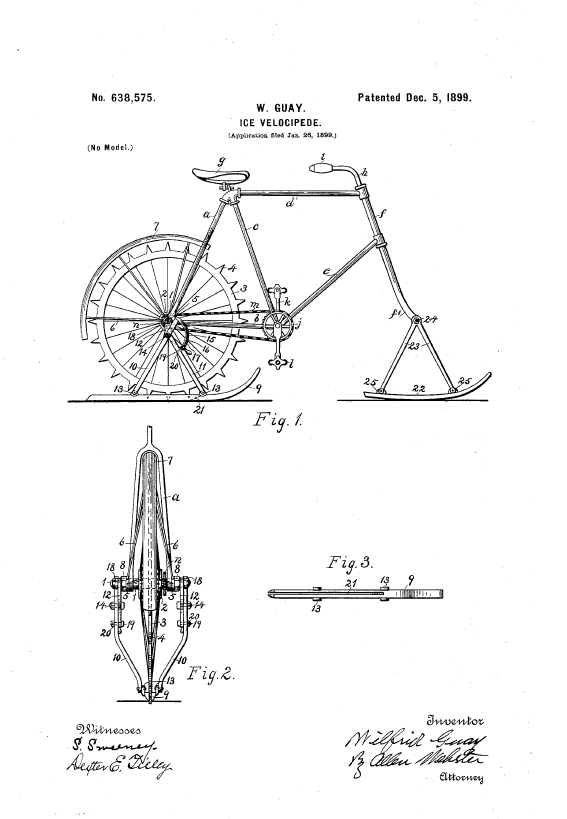

U.S. Patent No. 638,575 on an Ice Velocipede:

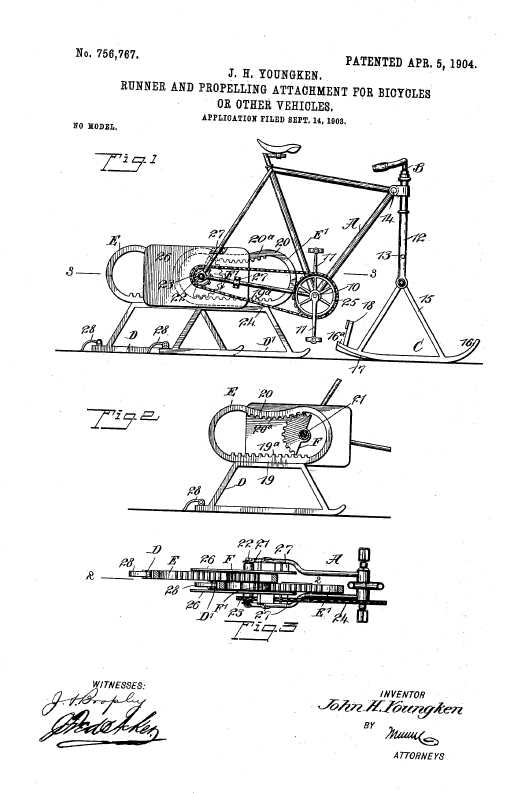

U.S. Patent No. 756,767 on a Runner and Propelling Attachment for Bicycles or Other Vehicles:

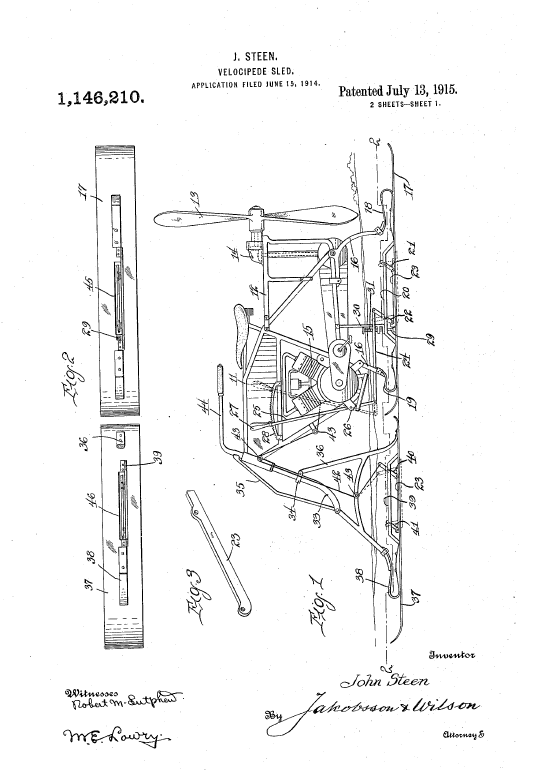

U.S. Patent No. 1,146,210 on a Velocipede Sled:

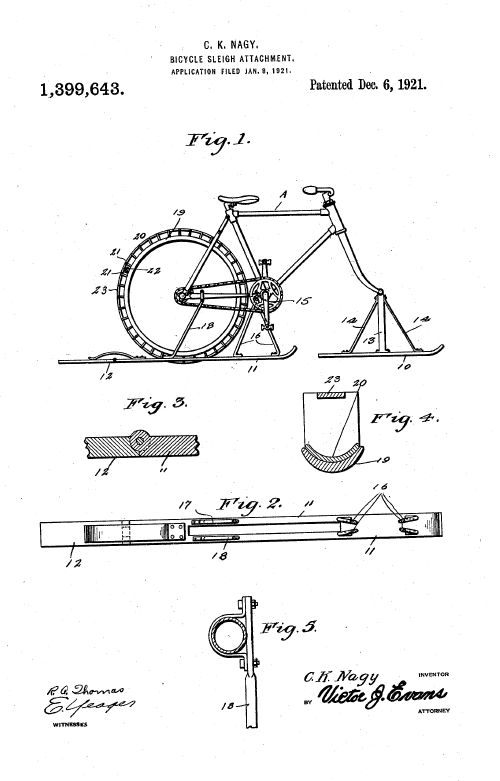

And some subsequent developments, including U.S. Patent No. 1,399,643 on a Bicycle Sleigh Attachment: