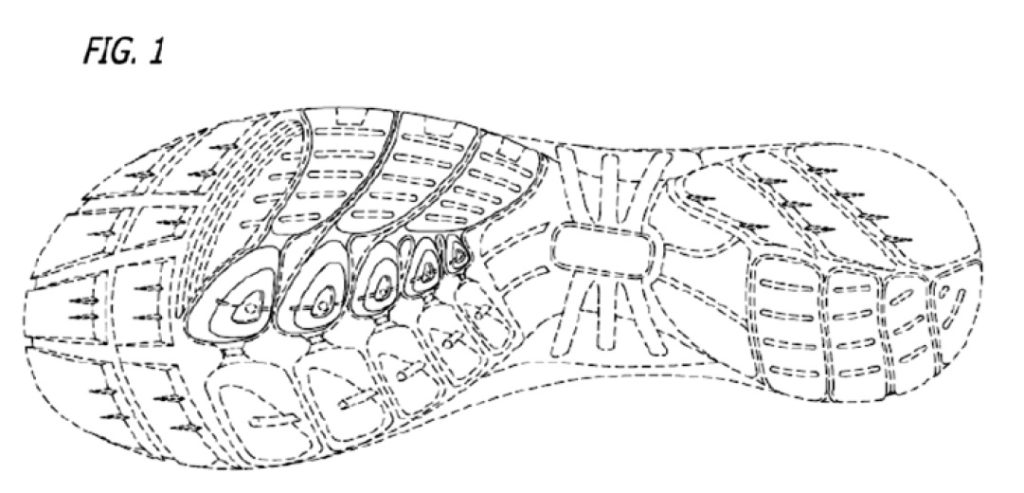

In In Re Maatita, [2017-2037] (August 20, 2018), the Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB affirmance of the rejection of Maatita’s design patent application on the design of an athletic shoe bottom.

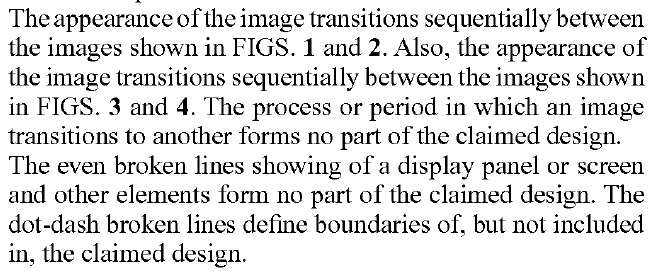

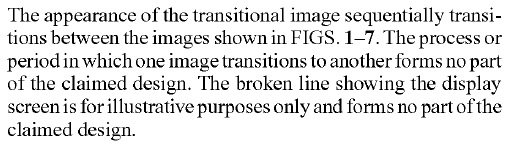

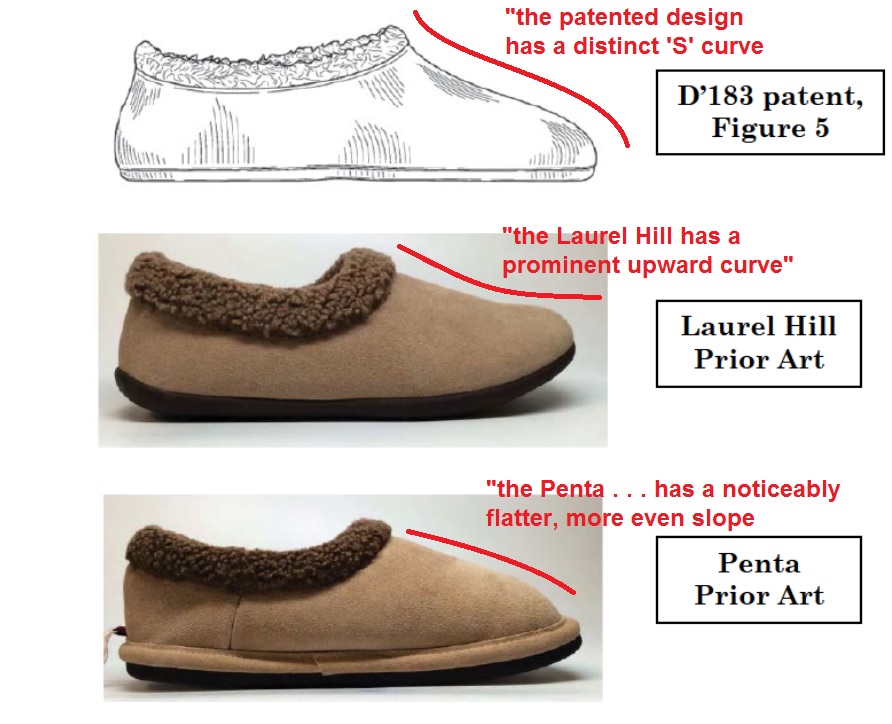

The Examiner rejected Maatita’s application containing a single two-dimensional plan-view drawing to disclose a shoe bottom design and left the design open to multiple interpretations regarding the depth and contour of the claimed elements. and indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112, and the PTAB affirmed.

The Examiner hypothesized four different designs, each of which were patentably distinct and therefore could not be covered by a single claim. Thus, the Examiner concluded that Maatita’s single claim was indefinite and not enabled, as one would not know which of the many possible distinct embodiments of the claim is applicant’s

in order to make and use applicant’s design. The Board concluded that because the single view does not adequately reveal the relative depths and three dimensionality between the surfaces provided, the Specification does not reveal enough detail to enable the claimed shoe bottom, under 35 U.S.C. § 112, first paragraph, and that the same lack of clarity and detail also makes the scope of the claim indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112, second paragraph.

The Federal Circuit noted that because patent claims are limited to what is shown in the application drawings, there is often little difference in the design patent context between the concepts of definiteness (whether the scope of the claim is clear with reasonable certainty) and enablement (whether the specification sufficiently describes the design to

enable an average designer to make the design). The Federal Circuit said that a visual disclosure may be inadequate—and its associated claim indefinite—if it includes multiple, internally inconsistent drawings. However errors and inconsistencies between drawings do not merit a § 112 rejection, however, if they do not preclude the overall understanding of the drawing as a whole. It is also possible for a disclosure to be inadequate when there are inconsistencies between the visual disclosure and the claim language. However, the Federal Circuit said the present case does not involve inconsistencies in the drawings, or inconsistencies between the drawings and the verbal description, but rather a single representation of a design that is alleged to be of uncertain scope. The Federal Circuit said the question was whether the disclosure sufficiently describes the design.

The purpose of § 112’s definiteness requirement, then, is to ensure that the disclosure is clear enough to give potential competitors (who are skilled in the art) notice of what design is claimed—and therefore what would infringe. With this purpose in mind, it is clear that the standard for indefiniteness is connected to the standard for infringement. Given that the purpose of indefiniteness is to give notice of what

would infringe, we believe that in the design patent context, one skilled in the art would assess indefiniteness from the perspective of an ordinary observer. Thus, a

design patent is indefinite under § 112 if one skilled in the art, viewing the design as would an ordinary observer, would not understand the scope of the design with reasonable certainty based on the claim and visual disclosure. So long as the scope of the invention is clear with reasonable certainty to an ordinary observer, a design patent

can disclose multiple embodiments within its single claim and can use multiple drawings to do so.

The fact that shoe bottoms can have three-dimensional aspects does not change the fact that their ornamental design is capable of being disclosed and judged from a

two-dimensional, plan- or planar-view perspective—and that Maatita’s two-dimensional drawing clearly demonstrates the perspective from which the shoe bottom should

be viewed. A potential infringer is not left in doubt as to how to determine infringement. In this case, Maatita’s decision not to disclose all possible depth choices would

not preclude an ordinary observer from understanding the claimed design, since the design is capable of being understood from the two-dimensional, plan- or planar-view

perspective shown in the drawing.

Because a designer of ordinary skill in the art, judging Maatita’s design as would an ordinary observer, could make comparisons for infringement purposes based on the

provided, two-dimensional depiction, Maatita’s claim meets the enablement and definiteness requirements of § 112. The Federal Circuit reversed the decision of the Board.

It seems that the Federal Circuit is exempting design patent inventors from their part of the quid pro quo for protection — a complete disclosure of the invention. Will the Supreme Court bother with another design patent case?