Lexicography – the power to define words – is heady stuff (at least for your typical mild-mannered patent prosecutor). It would seem that this power would be most responsibly applied to words that had no meaning, rather than redefining a word with an established meaning. Here are few examples of made up words and their meanings:

Doohickey

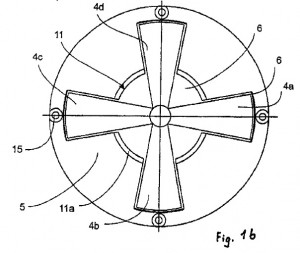

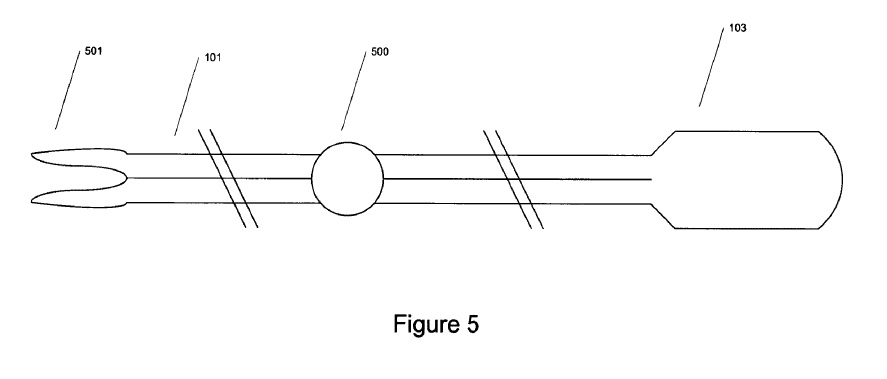

U.S. Patent No. 8,042,274 did not define doohickey in words, but rather instructs that a doohickey is shown in Fig. 5:

So at least now, you will know one when you seen one.

Thingamajig

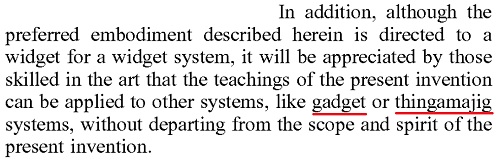

Thingamajig has not been expressly defined in any patent, but it must be a kind of disc drive system, appearing in two Seagate Technology patents (6,411,454 and 7,209,304), the latter stating:

an including a bonus reference to “gadget.” Speaking of gadget:

Gadget

Before its recent appropriation by computer geeks, “gadget” was a generic reference to a device, see in U.S. Patent No. 3,998,694, and sometimes a pejorative reference (e.g., 4,019,313 or 4,101,130). Appearing in nearly 2000 patents, “gadget” has taken a wide variety of meanings. In U.S. Patent No. 5,005,336 it is tool that helps turn a coconut into an envelope.

There are even devices to organize one’s gadgets: D316,502 and D312,559 and D303552, and even one to help you find them when they are lost: D726,691. Of course gadget was the code name for the first atom bomb, making all other uses trivial in comparison.

Doodad

U.S. Patent Nos. 6,398,058 and 7,004,347 gives us a definition of doodads: “small miscellaneous items, e.g., paper clips, rubber bands, buttons, etc.” and even provides a cup 10 to hold them. Although in U.S. Patent Nos. 6,106,300 and 6,890,179, a doodad is an “expense.”

Widget

U.S. Patent No. 9,225,817, explains that “widget” is “a contraction of ‘window gadget,'” and “refers to components in a graphical user interface (GUI).” However the use predates the computer age, and the word can be found in more than 7,000 patents.

Gizmo

Gizmo is used in more than 200 patents, mostly to refer to some non-specific device. It is apparently part of some prosecutor’s stock language, because most of the uses are along the lines of:

The words “comprising,” “including,” and “having” are always open-ended, irrespective of whether they appear as the primary transitional phrase of a claim, or as a transitional phrase within an element or sub-element of the claim (e.g., the claim “a widget comprising: A; B; and C” would be infringed by a device containing 2A’s, B, and 3C’s; also, the claim “a gizmo comprising: A; B, including X, Y, and Z; and C, having P and Q” would be infringed by a device containing 3A’s, 2X’s, 3Y’s, Z, 6P’s, and Q).