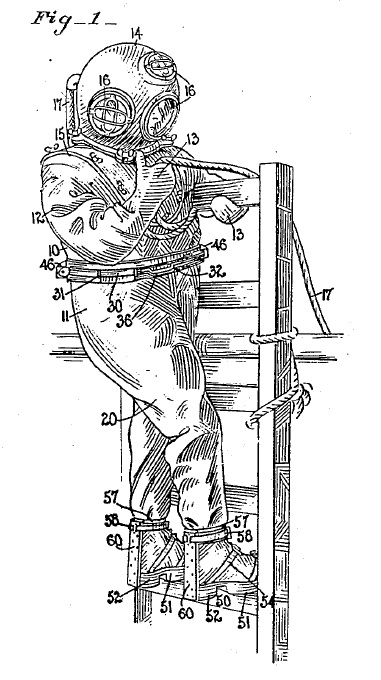

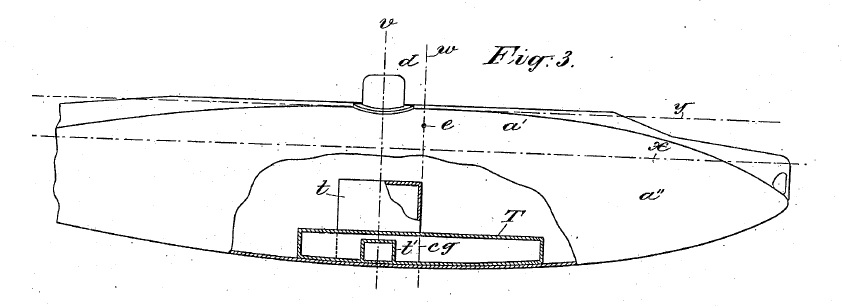

On March 1, 1921, U.S. Patent No. 1,370,316 issued to magician and escape artist Harry Houdini on a Diver’s Suit.

February 29 Patent of the Day

February 28 Patent of the Day

February 27 Patent of the Day

February 26 Patent of the Day

February 25 Patent of the Day

February 24 Patent of the Day

February 23 Patent of the Day

Broadest Reasonable Interpretation is Must be Consistent with the Specification and the Claims

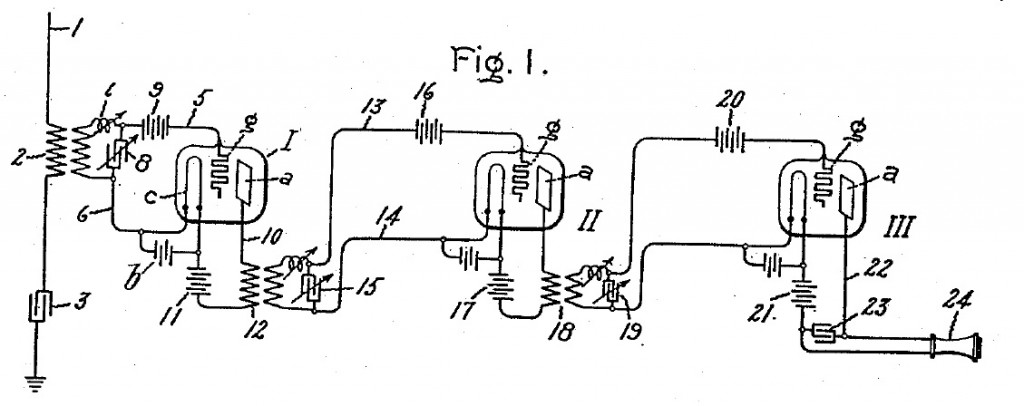

In PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc’ns RF, LLC (Fed. Cir. 2016), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the PTAB’s Final Written Decision in IPR2013-00342, because the construction adopted by the PTAB for “reside around” was broad, but not reasonable.

To the Federal Circuit, it appears that the Board “arrived at its construction by referencing the dictionaries cited by the parties and simply selecting the broadest definition therein.” The Federal Circuit said that while such an approach may result in the broadest definition, it does not necessarily result in the broadest reasonable definition in light of the specification. The Federal Circuit noted that the Board’s approach failed to account for how the claims themselves and the specification inform the ordinarily skilled artisan as to precisely which ordinary definition the patentee was using.

The Federal Circuit said that the fact that “around” had multiple dictionary meanings did not mean that all of these meanings are reasonable interpretations in light of the specification, and concluded that the interpretation selected by the Board was not reasonable. The Federal Circuit rejected a test of reasonableness based upon inclusion of as many of the disclosed embodiments as possible, indicating that above all, the broadest reasonable interpretation “must be reasonable in light of the claims and specification.” The Federal Circuit observed that the fact that one construction may cover more embodiments than another does not categorically render that construction reasonable.

Although the Federal Circuit did not explain the difference between the broadest reasonable interpretation and the ordinary meaning constructions, it noted that the case is much closer under the broadest reasonable interpretation standard given the ordinary meanings attributable to the term at issue.