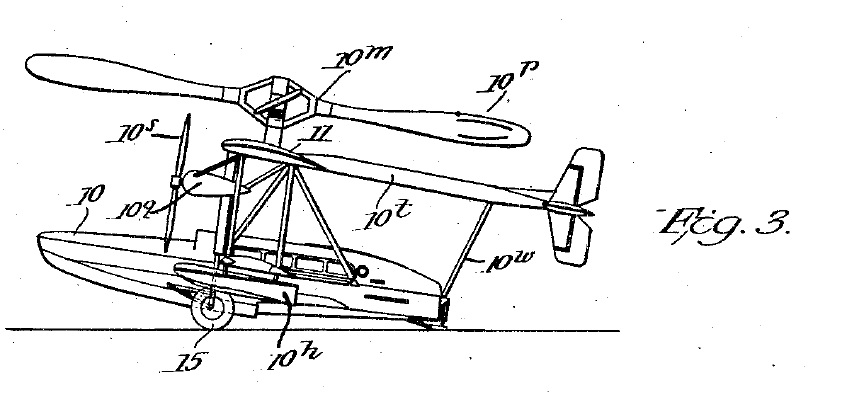

On March 8, 1932, U.S. Patent No. 1,848, 289, issued to Igor Sikorsky on Aircraft, Especially Aircraft of the Direct Lift Amphibian Type and Means of Constructing and Operating The Same — the helicopter.

The Privileged Few

In Queens’s University at Kingston, [2015-145] (March 7, 2016) the Federal Circuit granted a writ of mandamus directing the district court to withdraw its order compelling the production of Queen’s University’s communications with its non-attorney patent agents. The Federal Circuit said:

To the extent Congress has authorized non-attorney patent agents to engage in the practice of law before the Patent Office, reason and experience compel us to recognize a patent-agent privilege that is coextensive with the rights granted to patent agents by Congress. A client has a reasonable expectation that all communications relating to “obtaining legal advice on patentability and legal services in preparing a patent application” will be kept privileged.

Whether communications are directed to an attorney or his or her legally equivalent patent agent should be of no moment — to hold otherwise would frustrate the very purpose of Congress’s design: namely, to afford clients the freedom to choose between an attorney and a patent agent for representation before the Patent Office.

March 7 Patent of the Day

March 6 Patent of the Day

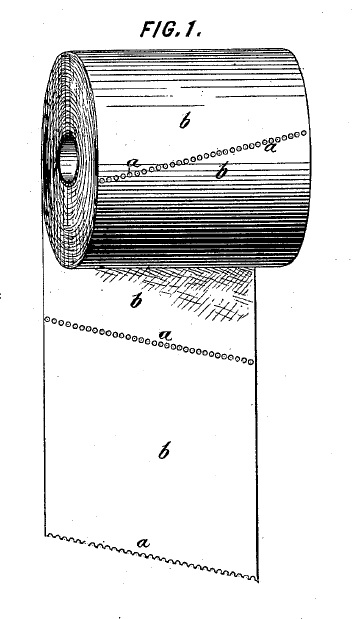

On March 6, 1646, Joseph Jenckes was awarded the first patent in North America by the General Court of Massachusetts, for making scythes. This basic scythe design remained in use for over 300 years.

March 5 Patent of the Day

March 4 Patent of the Day

March 3 Patent of the Day

On March 3, 1821, U.S. Patent No. X3306 issued to Thomas L. Jennings for a “dry scouring” cleaning process. Thomas was an African American businessman and abolitionist in New Your City, and was the first African-American to be issued a U.S. Patent.

March 2 Patent of the Day

Questions About Patent Validity Snuff Preliminary Injunction in Artificial Candle Case

In Luminara Worldwide, LLC v, Liown Electronics Co., Ltd., [2015-1671] (February 29, 2016), the Federal Circuit vacated a preliminary injunction on U.S. Patent Nos. 7,837,355; 8,070,319; and 8,534,869, directed to flickering artificial candles. The Federal Circuit rejected the accused infringer’s challenge that plaintiff did not have sufficient rights to enforce the patents, but agreed that there were substantial questions about the patent’s validity,

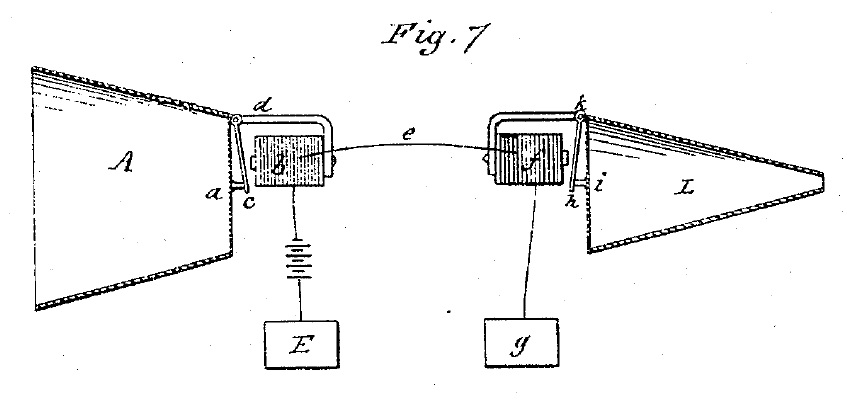

The Specification (Including the Title) Narrowed the Scope of the Claims

In Ultimatepointer LLC v. Nintendo Co., Ltd., [201501297] (March 1, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment of non-infringement of U.S. Patent No. U.S. Patent 8,049,729 on a handheld pointing device. At issue was whether the claims to a pointing device were covered the accused indirect pointing device, or were limited to direct pointing devices. i.e. devices for which the physical point-of-aim coincides with the item being pointed at. The district court found that the claims were limited to direct pointing devices, and thus were not infringed, and the Federal Circuit agreed.

The Federal Circuit balanced the rule against importing limitations from the specification into the claims, with the fact that repeated criticisms often indicate that subject matter was not intended to be within the scope of the claims.

We have cautioned against importing limitations from the specification into the claims when performing claim construction, Innogenetics, N.V. v. Abbott Labs., 512 F.3d 1363, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2008); however, we have also recognized that “repeated derogatory statements” can indicate that the criticized technologies were not intended to be within the scope of the claims, Chicago Bd. Options Exch. v. Int’l Sec. Exch., 677 F.3d 1361, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

The Federal Circuit noted that he specification repeatedly emphasizes that the invention is directed to a direct-pointing system, and repeatedly called the hand held device a direct pointing device. The Federal Circuit even pointed to the title, “Easily-Deployable Interactive Direct Pointing System . . .” as indicating that the invention is limited to direct pointing systems, citing Exxon Chem. Patents, Inc. v. Lubrizol Corp., 64 F.3d 1553, 1557 (Fed. Cir. 1995). The Federal Circuit also noted that the specification emphasized how direct pointing was superior to indirect pointing, and conversely how the written description disparaged indirect pointing.

The Federal Circuit said that taken together, the repeated description of the invention as a direct-pointing system, the repeated extolling of the virtues of direct pointing, and the repeated criticism of indirect pointing clearly point to the conclusion that the “handheld device” in the claims was limited to a direct-pointing device.