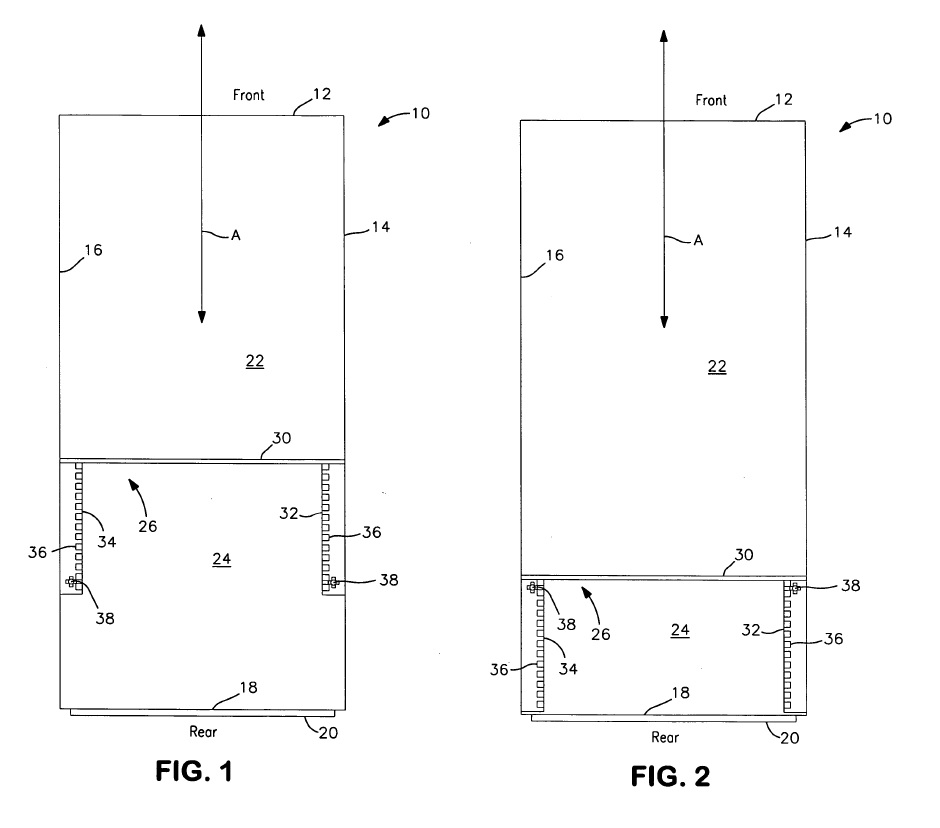

The use of trademarks in patent claims was previously discussed here. Trademarks continue to be used in patent claims, despite the potential for problems, not doubt because the trademark was seen as the best way to properly claim the invention. There is of course the concern that a trademark is indefinite, because the product can be changed at any time by the trademark owner. However changing meaning is a condition that can afflict any word in a claim, not just trademarks, granted changing meaning it is more likely with a trademark because it requires the action of a single person or entity, while changing the meaning of the work requires consensus.

Here are examples of trademarks recently used in patent claims:

AEROSIL– 10,154,954 (claim 2)

Android – 10,417,998 (claim 6), 10,417,008 (claim 6), 10,331,433 (claim 4).

ARSENSA – 10,154,954 (Claim 2)

Bluetooth – 10,420,011 (claim 9), 10,419,592 (claim 1), 10,365,866 (claim 10), 10,341,313 (claim 4), 10,321,516 (claim 6), 10,285,041 (claim 2), 10,027,169 (claim 7), 10,026,018 (claim 5), 9,998,996 (claim 7, 14), 9,955,515 (claim 8), 9,930,669 (claim 1), 9,912,794 (claim 1), 10,129,431 (claim 7, 16), 10,123,333 (claim 3, 14, 28), 10,019,852 (claims 2, 9,16), 9,980,059 (claims 1, 12, 23).

EPO-TEK – 10,330,233 (claim 17)

ETHERNET – 10,303,160 (claim 3,8)

Felica – 10,126,703 (claim 13)

Inconel – 10,392,728 (claim 10)

JAVA – 9,930,201 (claim 1)

JavaScript – 10,365,868 (claim 7)

Java Virtual Machine – 9,727,374 (claim 6)

Kahoot! 10,026,331 (claim 1)

KOVAR – 10,139,700 (claim 3)

Linux – 10,417,998 (claim 5), 10,417,008 (claim 5).

MIFARE – 10,126,703 (claim 13)

Monel – 10,392,728 (claim 10)

TRITON X – 10,254,276 (claim 5)

TWEEN – 10,254,276 (claim 5)

PARLEAM – 10,154,954 (claim 2)

QR Code – 10,223,625 (claim 5), 9,940,565 (claims 7, 10).

RLSA – 10,190,217 (claim 3), 10,017,853 (claim 7, 8)

SOFTISAN – 10,154,954 (claim 2)

VELCRO – 10,151,558 (claims 4, 7)

Vespel – 10,047,863 (claim 20)

VITRALI – 10,330,233 (claim 16)

Wi-Fi – 10,244,055 (claim 11), 10,044,903 (claims 6, 18), 10,129,431 (claims 6, 8, 17).

Wi-Fi Direct – 10,416,941 (claim 8), 10,342,071 (claim 12), 9,942,759 (claim 6).

Windows – 10,275,192 (claim 9).

ZIRCON – 10,240,814 (claims 1, 2, 9)

ZYLON – 10,201,999 (claim 8, 18)

Additional examples are relatively easy to find by search for the word trademark in the text of the claims, or searching for the R-in-the-circle symbol “.RTM.”

Although the meaning of a trademark can change over time, this is apparently understood by those of ordinary skill in the art, and rarely if ever is it necessary to specify that the meaning is determined “as of the filing date.”