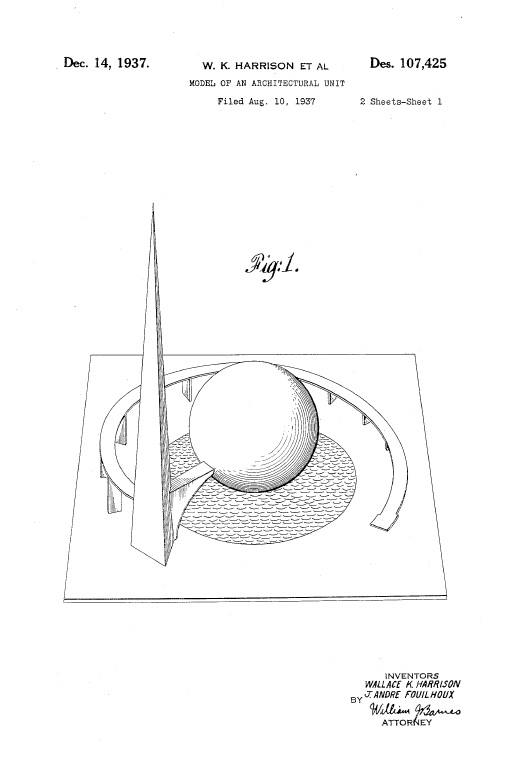

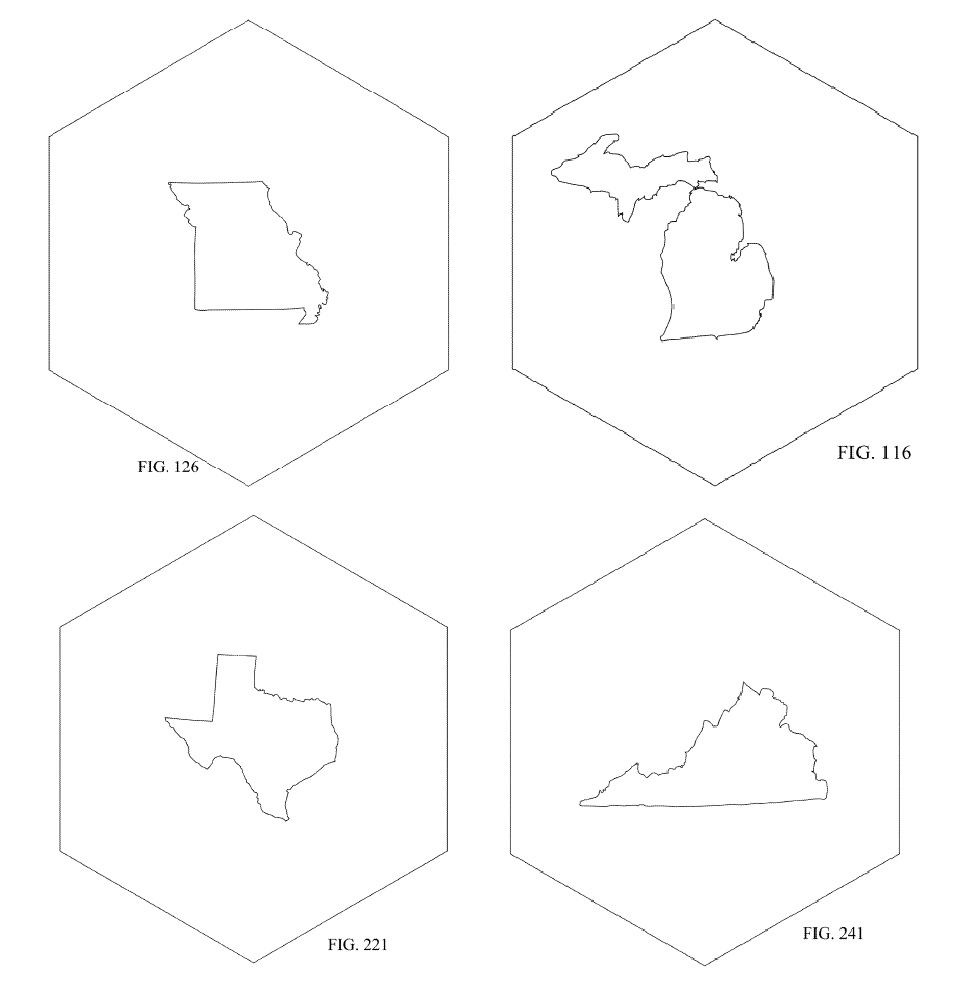

U.S. Patent No. D824219 issued on July 31, 2018 on a “Coaster State Bottle Opener.” This patent is interesting because it has 52 embodiments that are depicted in 260 Figures, featuring every state on its own coaster/bottle opener.

allow you to assemble a lovely coast collection featuring Harness, Dickey locations!

Applicants are of course entitled to present as many embodiments as they wish in a design patent application. MPEP 1504.05 states that “[m]ore than one embodiment of a design may be protected by a single claim. However, such embodiments may be presented only if they involve a single inventive concept according to the obviousness-type double patenting practice for designs.” If the embodiments do not involve a single inventive concept, the the Office will issue a restriction requirement, which can present a risk for the applicant, and discussed below. The MPEP sets out a two part test for determining whether embodiments involve a single inventive concept:

(A) the embodiments must have overall appearances with basically the same design characteristics; and (B) the differences between the embodiments must be insufficient to patentably distinguish one design from the other.

MPEP 1504.05

The presentation of multiple embodiments has the effect of broadening the scope of the claim, because the single design patent claim only covers the elements common to all of the embodiments. This is great from an infringement standpoint, but it also makes the design patent more vulnerable to a validity attack.

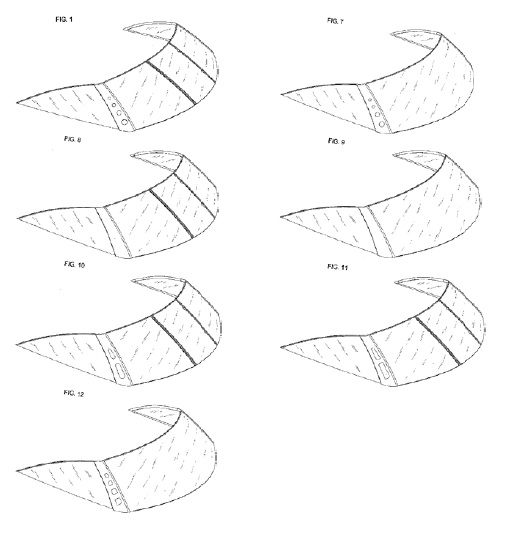

As mentioned above, restriction requirements can present difficulties for design patent applicants. If the applicant does not file a divisional application for each restricted embodiment, the applicant could be dedicating the non-pursued embodiments to the the public. This was the case in Pacific Coast Marine Windshields Ltd. v. Malibu Boats, LLC, (Fed. Cir. 2014), where the Federal Circuit held that when subject matter is surrendered during prosecution of a design patent (such as by acceding to a restriction requirement), prosecution history estoppel prevents the patentee from “recapturing in an infringement action the very subject matter surrendered as a condition of receiving the patent.” e claimed invention.

In Pacific Coast Marine, during prosecution of the patent in suit (D689782) the Examiner identified five separate embodiments, but the applicant protected only two, leaving the other three embodiments unprotected.

Just because one can include multiple embodiments in a design application does not mean it is always a good idea. Thought should be given to whether the same protection can be achieved through a single embodiment with unimportant details shown in dashed lines (and thus excluded from the scope of the claims), and/or whether multiple applications would would provide better protection (albeit at a higher cost). Multiple embodiments can complicate both validity and infringement determinations.