In Halo Electronics, Inc. v. Pulse Electronics, Inc., 579 U.S. — (2016), the Supreme Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s two-step Seagate test for the award of enhanced damages under 35 USC 284, holding that the aware of enhanced damages was within the discretion of the trial court, subject to review for abuse of that discretion.

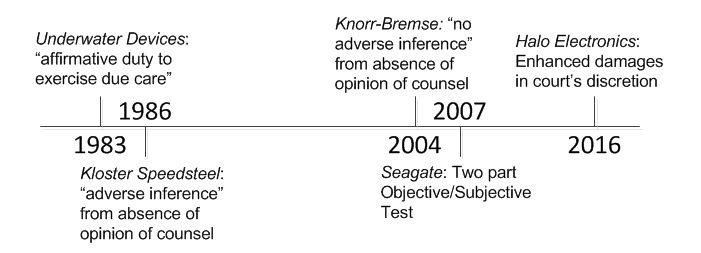

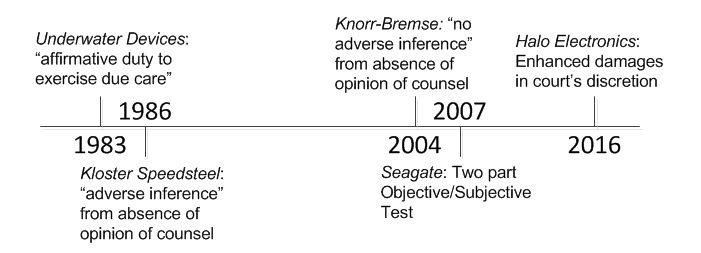

The award of enhanced damages under Section 284 has had ups and downs under the Federal Circuit’s supervision. Shortly after the Federal Circuit was created, in Underwater Devices, the Federal Circuit announced an “affirmative duty to exercise due care.” Three years later in Kloster Speedsteel, the Federal Circuit created an adverse inference from not introducing an opinion of counsel to demonstrate a lack of willfulness. This adverse inference persisted until 2004, when the Federal Circuit recognized the gamesmanship surrounding opinions of counsel, and eliminated the adverse inference in Knorr-Bremse. Then in 2007 the Federal Circuit raised the bar higher in Seagate establishing a two part, objective/subjective test.

Under Seagate, a patent owner must first show by clear and convincing evidence that the infringer acted despite an objectively high likelihood that its actions constituted infringement of a valid patent. Second, the patentee must demonstrate, again by clear and convincing evidence, that the risk of infringement was either known or so obvious that it should have been known to the accused infringer. The Supreme Court said that this test is not consistent with 35 USC 284.

§284 provides simply that “the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.” The Supreme Court noted that the statute contains no explicit limit or condition, and that the word “may” clearly connotes discretion. However discretion is not without limits: a motion to a court’s discretion is a motion, not to its inclination, but to its judgment; and its judgment is to be guided by sound legal principles.

The Supreme Court instructed that awards of enhanced damages under the Patent Act over the past 180 years establish that they are not to be meted out in a typical infringement case, but are instead designed as a “punitive” or “vindictive” sanction for egregious infringement behavior. The Court said that:

The sort of conduct warranting enhanced damages has been variously described in our cases as willful, wanton, malicious, bad-faith, deliberate, consciously wrongful, flagrant, or—indeed—characteristic of a pirate.

Seagate reflects a sound recognition that enhanced damages are generally appropriate under §284 only in egregious cases, but the Supreme Court found the test “unduly rigid, and it impermissibly encumbers the statutory grant of discretion to district courts.” In particular, the court was critical of the requirement of a showing of objective recklessness, finding no reason for the requirement in the context of deliberate wrongdoing. The Federal Circuit said that the requirement of objective recklessness insulates an infringer from enhanced damages, so long has he or she can mount a reasonable defense, even if he did not act on the basis of a defense or was even aware of it. The Supreme Court complaint that:

Under that standard, someone who plunders a patent—in- fringing it without any reason to suppose his conduct is arguably defensible—can nevertheless escape any come- uppance under §284 solely on the strength of his attorney’s ingenuity.

The Supreme Court said that culpability is generally measured against the knowledge of the actor at the time of the challenged conduct. The Court found no reason to look to facts that the defendant neither knew nor had reason to know at the time he acted. The Court said that Section 284 allows district courts to punish the full range of culpable behavior, although nothing says they must do so. As with any exercise of discretion, courts should continue to take into account the particular circumstances of each case in deciding whether to award damages, and in what amount. Consistent with nearly two centuries of enhanced damages under patent law, however, such punishment should generally be reserved for egregious cases typified by willful misconduct.