On July 16, 1895, U.S. Patent No. 542,846 issued to Rudolf Diesel on his Method of and Apparatus for Converting Heat into Work (the Diesel Engine.

I win? No Fair!

In SkyHawke Technologies, LLC v, Deca International Corp., [2016-1325, 2016,1326] (July 15, 2015), the Federal Circuit granted Deca’s motion to dismiss SkyHawke’s appeal of a PTAB Decision in a reexamination on the grounds that SkwHawke was the prevailing party.

Even though SkyHawke “won” the reexamination, SkyHawke did not like the PTAB’s construction of its claim, and wanted the Federal Circuit to correct the PTABs’ claim construction. The Federal Circuit observed that Courts of appeals employ a prudential rule that the prevailing party in a lower tribunal cannot ordinarily seek relief in the appellate court. Even if the prevailing party alleges some adverse impact from the lower tribunal’s opinions or rulings leading to an ultimately favorable judgment, the matter is generally not proper for review.

The Federal Circuit found that SkyHawke’s appeal fits cleanly into this prudential prohibition. The Federal Circuit noted that the PTAB’s decision is not issue-preclusive precisely because SkyHawke cannot appeal it.

The Federal Circuit said that SkyHawke will have the opportunity to argue its preferred claim construction to the district court, and SkyHawke can appeal an unfavorable claim construction should that situation arise. With the present appeal, SkyHawke is merely trying to preempt an unfavorable outcome that may or may not arise in the future and, if it does arise, is readily appealable at that time. Therefore, the Federal Circuit found no reason to deviate from the standard rule counseling against our review of prevailing party appeals.

Sale of Manufacturing Services Does Not Trigger On Sale Bar Under Pre-AIA §102

In The Medicines Company v. Hospira, Inc., [2014-1469, 2014,1504] (July 11, 2016), the en banc Federal Circuit reversed a panel decision finding that U.S. Patent Nos. 7,582,727 and 7,598,343 were invalid under the on-sale bar of §102(b), because of the sales activities of the patent owner’s contract manufacturer,

The Federal Circuit reviewed this history of the §102(b) bar, and the Supreme Court’s two-part Pfaff test, under which the challenger must show (1) the invention was subject to a commercial sale, and (2) the invention was ready for patenting. Unlike most cases which focus on the second prong of the test, this case focused on the first prong. The Federal Circuit clarified that the mere sale of manufacturing services by a contract manufacturer to an inventor to create embodiments of a patented product for an inventor does not constitute a “commercial sale” of the invention. The Federal Circuit identified three reasons for its decision:

- only manufacturing services were sold to the inventor — the invention was not;

- the inventor maintained control of the invention –retaining title, and the manufacturer was not authorized to sell to third parties.

- “stockpiling” inventory without more does not trigger the on-sale bar.

Even though this case applies to the pre-AIA version of §102, it will have relevance for many years until the last of the pre-AIA patents expire.

It Ain’t Over ‘Till It’s Over

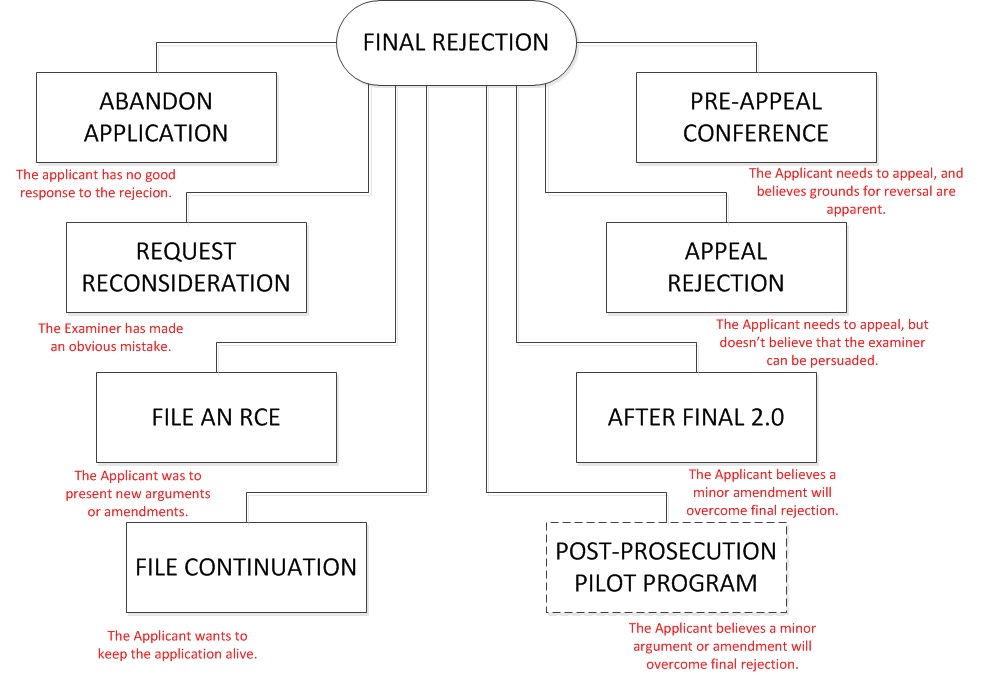

It seems that the majority of patent applications, including those that eventually issue as patents, face a “final” rejection at some point. However, “final” does not not always mean final, and there are at least eight possible responses to a final rejection.

ABANDON APPLICATION

As much as patent prosecutors hate to admit it, every once in a while the Patent Examiner is right, and the only reasonable response to the Final Office Action is to abandon the application.

REQUEST RECONSIDERATION/AMENDMENT AFTER FINAL

Sometimes a Final Office Action will be premised on an a clear mistake of law or fact, which if pointed out the the Examiner, will result in the withdrawal of the finality of the action, and perhaps even an allowance. 37 CFR §§1.113 and 1.116 address responses after a Final Office Action. 37 CFR §1.116 limits amendment to three situations:

- An amendment may be made canceling claims or complying with any requirement of form expressly set forth in a previous Office action

- An amendment presenting rejected claims in better form for consideration on appeal may be admitted; or

- An amendment touching the merits of the application or patent under reexamination may be admitted upon a showing of good and sufficient reasons why the amendment is necessary and was not earlier presented.

Generally, an Examiner will not permit an amendment unless it complies with 37 CFR §1.116. Examiners have no incentive to give any substantial attention to a response after final, and they are rarely effective unless they fully comply with the requirements set forth in the Final Rejection.

FILE A REQUEST FOR CONTINUED EXAMINATION (RCE)

If an applicant wants to continue to prosecute the application, presenting additional arguments and evidence, or amending the claims, then the applicant can request continued examination under 37 CFR §1.114. If an applicant timely files a submission and fee set forth in §1.17(e), the Office will withdraw the finality of any Office Action and the submission will be entered and considered.

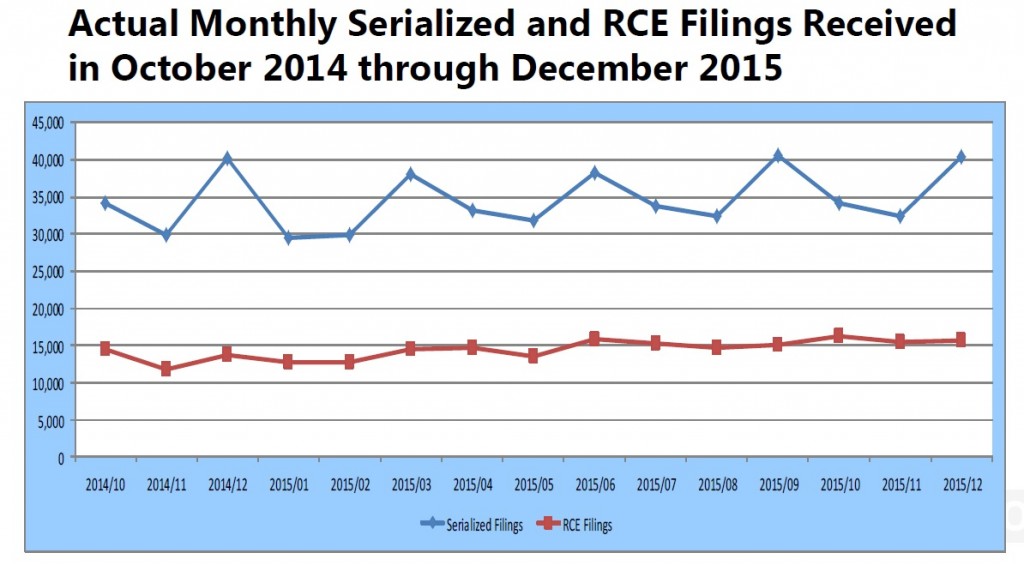

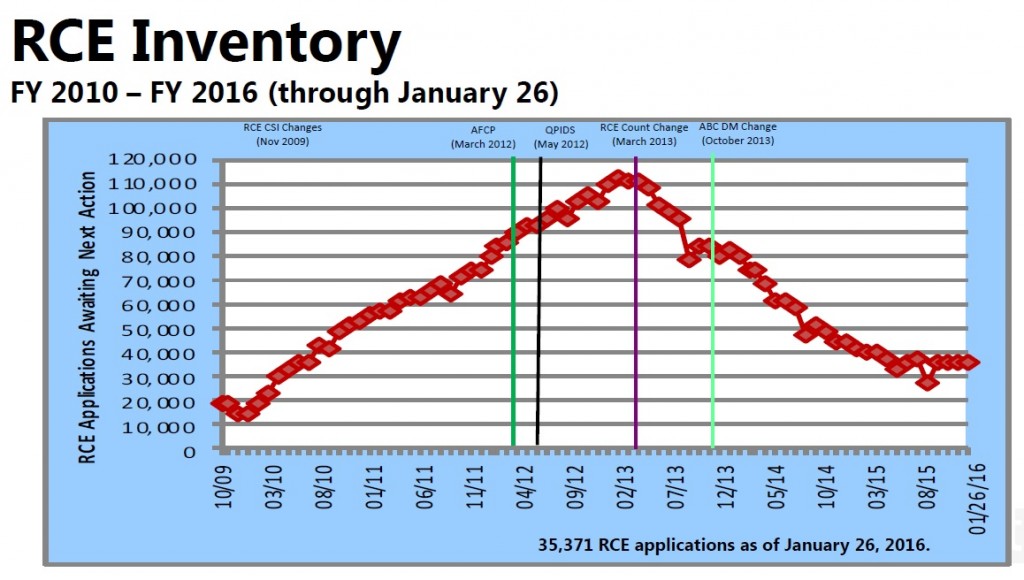

RCE’s are a significant part of patent prosecution. USPTO Statistics show taht approximately 30% of the applications waiting examination are applications in which an RCE has been filed:

The USPTO treatment of RCE’s has changed over time — in 2009 the USPTO changed the Examiner’s incentives to handle RCE, which resulted in a large backlog, but various changes in USPTO policies have resulted in a steady decline in pendency.

FILE A CONTINUATION APPLICATION

An application is always free to restart the application process by filing a continuation application. Unlike an RCE which keeps its original serial number and filing date, a continuation application is a new application, which is assigned a new serial number and filing date (although it claims priority to the parent application). Continuation applications are put at the bottom of the examination pile, and are a good choice for an applicant who wants to keep the application alive, but is not in a position to provide a complete response to the final rejection, which would be required to file an RCE.

AFTER FINAL 2.0

Although a response after final generally won’t be considered, several years ago the USPTO created an After Final Consideration Pilot 2.0 that gives Examiner a limited additional amount of time (and thus an incentive) to consider compliant submissions under the pilot program. The current version of the program, which expires September 30, 2016, requires that the applicant file:

- A request for consideration under AFCP 2.0 (Form PTO/SB/434); and

- A response under 37 CFR 1.116, including an amendment to at least one independent claim that does not broaden the scope of the independent claim in any aspect.

In response to the AFCP submission, the applicant will receive an AFCP 2.0 response form (PTO-2323) that communicates the status of the submission. If the applicant requested an interview, the the form will also be accompanied by an interview summary.

One can request an examiner interview after final in the ordinary course, but it is up to the discretion of the examiner as to whether to grant that interview request. Here, under the AFCP 2.0 program, the examiner is given additional time to search and/or consider the response, but also it gives applicants an additional opportunity to discuss the application with the examiner, if the response does not place the application in a condition for allowance. To date, the USPTO has not published statistics on the AFCP 2.0 program.

POST-PROSECUTION PILOT PROGRAM (P3)

A new alternative for patent applications beginning July 11, 2016, and extending to January 12, 2017, is the Post-Prosecution Pilot Program or P3 Program. The P3 Program provides for (i) an after final response to be considered by a panel of examiners (like the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference), (ii) an after final response to include an optional proposed amendment (like the AFCP 2.0), and (iii) an opportunity for the applicant to make an oral presentation to the panel of examiners (new).

The request for the P3 Program should include:

- A transmittal form, such as form PTO/SB/ 444, that identifies the submission as a P3 submission and requests consideration under the P3 Program

- A response under 37 CFR 1.116 comprising no more than five pages of argument; and

- A statement that the applicant is willing and available to participate in the conference with the panel of examiners.

- (Optionally) A proposed non-broadening amendment to a claim(s).

PRE-APPEAL BRIEF CONFERENCE

For applicants who have made all the amendments they are willing to make, and presented all of the arguments it has, the is one last stop before an full-blown appeal to the Patent Trials and Appeals Board: the pre-appeal brief conference.

The request must be filed with the Notice of Appeal, and can include up to five pages of reasons why the final rejection is incorrect. The point of the pre-appeal conference is that the Examiner must discuss (hence “conference) the final rejection with at least two other Examiners. The hope of applicants, of course, is that the two other Examiner’s will provide a voice of reason so that the final rejection will be withdrawn and the case allowed. However that is only one of the possible outcomes.

In 2015, IP Watchdog posted the results of a FOIA request for data on the effectiveness of the Pre-Appeal Brief Conferences, the data showed that of the non-defective requests, only 6% resulted in an allowance. 61% of the time, the conference panel decided that there was an issue for appeal. 33% of the time, the conference resulted in a reopening of prosecution, which is at least a partial victory for the applicant.

Drilling down a little further, of the 61% of applications where the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference found an appealable issue, 58% of these applications eventually issued as patents. Of the 33% of applications where the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference reopened prosecution, nearly 80% of these applications eventually issued as patents. This data represented the ten years’ experience between when the program began in 2005 through 2015, although the trend since 2009 has been an ever-increasing percentage of Pre-Appeal Brief Conferences finding an appealable issue.

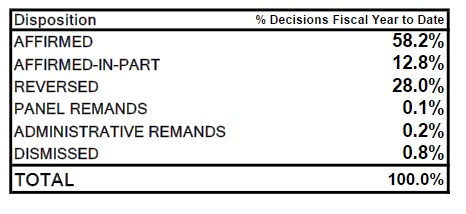

APPEAL

After all the amendments have been made and arguments presented, an applicant is left with no choice but to appeal, The cost of an appeal is not insignificant, with a Notice of Appeal Fee, the cost of preparing the Brief on Appeal, and the Appeal consideration fee, an applicant can easily spent $8,000 to $12,000, before oral argument. The time involved is also considerable — typically three to four years. The current (2016) success rate is about 40%, with Examiner being affirmed about 58.2% of the time, being reversed about 28.0% of the time, and partially reversed another 12.8% of the time.

i

And in the Alternative . . .

The older among us have “unlearned” the prohibition of the word “or” in patent claims, and have reasoned that if “or” is acceptable, its cousin “and/or” is acceptable in patent claims as well. A few years ago, the USPTO confirmed this in Ex Parte Gross, App. 11/565/441, (PTAB 2014). Mr. Gross claimed:

forming a website collective whose members include a plurality of different websites characterized by a common parameter including at least one of a common content topic, and/or a common contractual arrangement.

The Examiner took exception to “and/or” rejecting the claim as indefinite. The Board of Appeals reversed the Examiner, agreeing with Mr. Gross that “‘and/or’ covers embodiments having element A alone, element B alone, or elements A and B taken together.” The Board did add that the preferred verbiage” would be “at least one of A and B” and not “at least one of A an/or B.”

Thus “and/or” in a claim is not necessarily indefinite, but it is not the preferred way to write a claim.

The Commercial Marketing Provisions of the Biologics Act are Mandatory

In Amgen Inc. v. Apotex Inc., [2016-1308] (July 5, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed a preliminary injunction against Apotex from entering the market until 180 days after giving Amgen Notice after receiving its FDA license.

The Federal Circuit held that the commercial marketing provision of the Biologics Act was mandatory.

Not All Processes That Employ Only Independently Known Steps are Unpatentable

In Rapid Litigation Management Ltd. v. Cellzdirect, Inc., [2015-1570] (July 5, 2016), the Federal Circuit vacated summary judgment that U.S. Patent No. 7,604,929 on hepatocytes capable of surviving multiple freeze-thaw cycles was invalid under §101 as directed to a patent ineligible law of nature.

The Federal Circuit analyzed the claims, directed to a method of produce a desired preparation of multi-cryopreserved hepatocytes” finding that the claims are “simply not directed to the ability of hepatocytes to survive multiple freeze-thaw cycles” as the district court erroneously found. instead, the Federal Circuit said, the claims are directed to a new and useful laboratory technique for preserving hepatocytes. The Court said:

This type of constructive process, carried out by an artisan to achieve “a new and useful end.” is precisely the type of claim that is eligible for patenting.

The Federal Circuit observed that the inventors discovered the cells’ ability to survive multiple freeze-thaw cycles, but that is not where they stopped nor was that what they patented. As the first party with the knowledge of the cells ability, they were in an excellent position to claim applications of that knowledge.

Although the Federal Circuit found the subject matter patentable at Step 1 of the Alice/Mayo two part test, the Federal Circuit said that it would have passed Step 2 of the test even though each of the individual steps was well known. The Federal Circuit said that not all processes that employ only independently known steps are unpatentable. To the contrary, the claims must be viewed as a whole, considering their elements both individually, and as an ordered combination.

In the present case the steps of freezing and thawing were well known, but a process of preserving cells by repeating those steps was itself far routine and conventional. Repeating a step that the art taught should be performed only once “can hardly be considered routine or conventional.” To require something more at step two ” would be to discount the human ingenuity that comes from applying a natural discovery in a way that achieves a new and useful end.

Plausibility vs. Enablement

U.S. Patent No. 8,330,305 covers protecting devices from impact damage. The patent claims detecting that the portable device will impact a surface, and, if the risk of damage to the portable device from the impact exceeds a damage threshold; altering the orientation of the portable device so that the air bag will impact the surface first, and deploying the airbag before the device impacts the surface.

The embodiment shown appears to be a cell phone, and it is hard to imagine that a reasonably sized cell phone could contain both an airbag and a system that could reorient the cell phone in a ~42 inch drop from the hands of a user. In 7200 words and a dozen figures, the disclosure seems to barely meet the plausibility threshold, let alone enablement required under 35 USC 112(a).

Inventive Concept Can be Found in Non-conventional and Non-generic Arrangement of Known, Conventional Pieces

In Bascom Global Internet Services, Inc., v. AT&T Mobility LLC, [2015-1763] (June 27, 2016), the Federal Circuit reversed the dismissal of of the Complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted on the grounds that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

AT&T argued that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “filtering Internet content,” which is a well-known “method of organizing human activity” like the intermediated settlement concept that was held to be an abstract idea in Alice. BASCOM responded by arguing that the claims are not directed to an abstract idea because they address a problem arising in the realm of computer networks, and provide a solution entirely rooted in computer technology, similar to the claims at issue in DDR

Holdings.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that filtering content is an abstract idea because it is a longstanding, well-known method of organizing human behavior, similar to concepts previously found to be abstract. The Federal Circuit said that the claims and their specific limitations do not readily lend themselves to a finding that they

are directed to a nonabstract idea, so it defered consideration of the specific claim limitations’ narrowing effect for step two of the Alice analysis.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the limitations of the claims, taken individually, recite generic computer, but disagreed with the district court’s analysis

of the ordered combination of limitations. The Federal Circuit said that The inventive concept inquiry requires more than recognizing that each claim element, by itself, was

known in the art. The Federal Circuit said that an inventive concept can be found in the non-conventional and non-generic arrangement of known, conventional pieces.

The Federal Circuit said that on this limited record before it, the specific method of filtering Internet content cannot be said, as a matter of law, to have been conventional or generic. The Federal Circuit found that the claims do not merely recite the abstract idea of filtering content along with the requirement to perform it on the Internet, or to perform it on a set of generic computer components.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of filtering content, but that BASCOM had adequately alleged that the claims pass step two of Alice’s two-part framework.

A Combination of References Can be Obvious Even it Requires a Bit of Work

In Allied Erecting v. Genesis Attachments, LLC, [2015-1533](June 15, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision in IPR2014-001006 that claims 1–21 of U.S. Patent No. 7,121,489, were obvious.

Allied first challenged the motivation to combine the references, arguing that the proposed combination would would entail design and structural changes. However, the Federal Circuit said that it is not necessary that the reference be physically combinable to render the claimed invention obvious. The criterion is not whether the

references could be physically combined but whether the claimed inventions are rendered obvious by the teachings of the prior art as a whole. The Federal Circuit added that the fact that a modification has simultaneous advantages and disadvantages does not necessarily obviate motivation to combine.

Allied also argued that the references teach away from the combination. The Federal Circuit disagreed that the reference taught away from the combination, saying that teaching away is when a person of ordinary skill would be discouraged from following the path set out in the reference, or would be led in a direction divergent from the path that was taken by the patentee. The Federal Circuit noted that the reference did not teach away from the combination because the reference did not address the structure of the second reference.