Patents to celebrate the day:

Patents to celebrate the day:

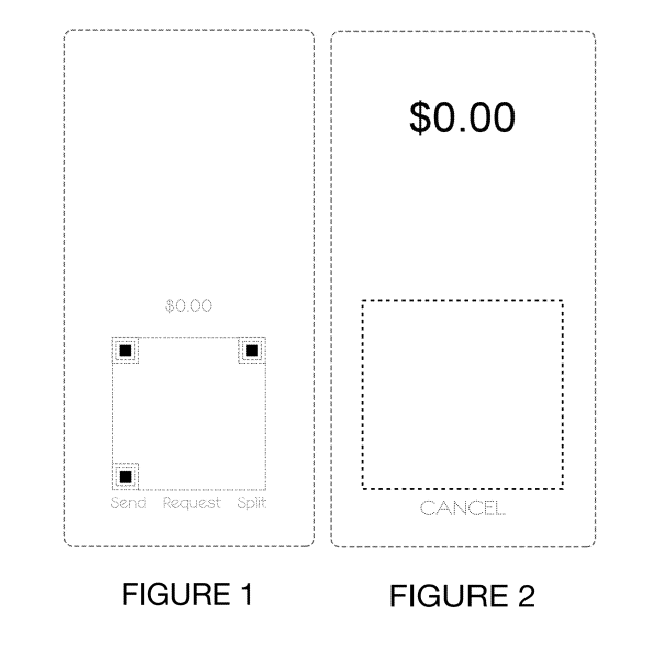

On September 14, 2021, U.S. Patent No. D930702, on a Display Screen Portion with Animated Graphical User Interface, issued to Wepay Global Payments LLC. The design patent covers two embodiments: The first embodiment consists of Figs. 1 and 2:

The second embodiment consists of Figs. 3 – 5:

Within weeks of the patent issuance Wepay sued PNC Bank NA. A month later Wepay sued PayPal Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co. Last month Wepay sued JPMorgan Chase Bank NA and Bank of America NA. Then last week, Wepay sued Apple (6:22-cv-00223 in W.D.Texas), Amazon (1:22-cv-01061 in N.D. Ill), Tesla (W.D. Texas), Walmart Stores Inc (1:22-cv-01062 in N.D. Ill.))., and McDonald’s Corp. (1:22-cv-01064 in N.D. Ill.)

With the patent’s liberal use of dashed lines, it appears that Figs. 1 and 3 cover any screen with the a QR code finder pattern – the three black squares in three corners of the QR code. Figs. 2 and 5 cover any screen with the figure “$0.00.” Fig. 4, oddly enough, covers any screen, with or without content.. Since QR codes have been around since 1994, and dollar signs even longer — since the late 18th century, it seems unlikely that this pattern did not appear on an apps display before the September 3, 2020, filing date of the ‘702 patent.

Wepay is asserting the ‘702 to its broadest extent. Looking, for example at the complaint against Apple,

It is hard to fathom what is ornamental about the three squares of a QR code, or the dollar sign or zeros. It is also hard to imagine that if the defendants are infringing now, that they were not infringing before the patent was filed, thus invalidating the patent.

Give the tremendous resources of the defendants, it is difficult to imagine that this patent will be found valid and infringe, we can only hope they don’t destroy the design patent system in the process.

The purpose of the patent system is to promote the progress of science and the useful arts. It does so in two ways: First, it incentives invention by providing inventors exclusive rights to new inventions for a limited time. Second, it encourages disclosure and provides a database of information in the form of millions of technical disclosures about all sorts of topics. It is amazing what you can learn from patents, and one such fun fact appropriate for today is that the last name of Punxsutawney Phil, the hero of the day, is Sowerby! This fun fact appears in U.S. Patent No. 10296823, which in Col. 34, lines 21-30, explains the difference between connection and dependency with a Groundhog Day Example:

February is Black History Month, honoring the triumphs and struggles of African Americans throughout U.S. history. Among these triumphs are the inventions black inventors have contributed, many of which were not recognized with a patent because the Patent Acts of 1793 and 1836 barred slaves from obtaining patents because they were not considered citizens. It was not until the Patent Act of 1870 that “any person or persons” having discovered or invented any new and useful art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter could apply for and obtain a patent. The breadth and importance of inventions contributed by black inventors is one of the best examples of the value of diversity:

Dry Cleaning

Most historians agree that the first U.S. patent that issued to a black inventor was U.S. Patent No. X3306, issued to Thomas L. Jennings over two hundred years ago on March 3, 1821, on dry scouring — a method of dry cleaning.

Planter

The second patent that issued to a black inventor was U.S. Patent No. 8447X, issued to Henry Blair (inventor) – Wikipedia on a (Corn) Seed Planter. He also received U.S. Patent No. 15 on a Corn Planter.

Locomotive Lubricators

Elijah McCoy, was a prolific inventor. Among his 57 U.S. patents was U.S. Patent No. 129843 for Improvements in Lubricators for Steam-Engines, on July 28, 1872. It is reputed that his invention was so often duplicated, that people began asking for the “real McCoy.”

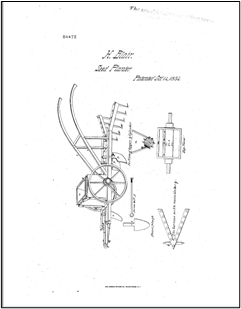

Uses for Peanuts

George Washington Carver was a famous scientist and prolific inventors, although he only patented two of his inventions, U.S. Patent 1,522,176, on Cosmetic and Process of Producing the Same, and U.S. Patent 1,632,365, on Process of Producing Paints and Stains.

amd

In Nature Simulation Systems Inc. v. Autodesk, Inc., [2020-2257](January 27, 2022), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s judgement that U.S. Patent Nos. 10,120,961 and 10,109,105, both entitled

“Method for Immediate Boolean Operations Using Geometric Facets” were not invalid for indefiniteness.

The patents are for data structures and algorithms for the claimed method, which is described as a modification of a the Watson method a Boolean operation published in 1981 for analyzing and representing three-dimensional geometric shapes. There were two claim elements that the district court determined made the claims indefinite: “searching neighboring triangles of the last triangle pair that holds the last intersection point”; and “modified Watson method.” The district court held the claims indefinite based on the “unanswered questions” that were suggested by Autodesk’s expert.

In finding the claims indefinite, the district court declined to consider information in the specification that was not included in the claims. The Federal Circuit found that the district court misperceived the function of patent claims. The Federal Circuit also found that the applicant, in consultation with the examiner, amended the claim to add the disputed language. The Federal Circuit noted that the district court gave no weight to the prosecution history showing the resolution of indefiniteness by adding the designated technologic limitations to the claims. The court did not discuss the Examiner’s Amendment, and held

that since Dr. Aliaga’s questions were not answered, the claims are invalid.

The Federal Circuit said that “[a]ctions by PTO examiners are entitled to appropriate deference as official agency actions, for the examiners are deemed to be experienced in the relevant technology as well as the statutory requirements for patentability.” The Federal Circuit added “[t]he subject matter herein is an improvement on the known Watson and Delaunay methods, and partakes of known usages for established technologies. Precedent teaches that when ‘the general approach was sufficiently

well established in the art and referenced in the patent’ this ‘render[ed] the claims not indefinite.’”

The Federal Circuit concluded that ‘[I]ndefiniteness under 35 U.S.C. § 112 was not established as a matter of law,” and reversed the district court.

In Evolusion Concepts, Inc. v. HOC Events, Inc., [2021-1963] (January 14, 2022) the Federal Circuit reversed the grant of summary judgment of non-infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,756,845 on a “Method and Device for Converting Firearm with Detachable Magazine to a Firearm with Fixed Magazine,” , reversed the denial of summary judgment of direct infringement as to the independent claims 1 and 8, and remanded for further proceedings.

The district court held that the term “magazine catch bar” in the asserted claims of the ’845 patent excludes a factory installed magazine catch bar. Claim 15 requires removing “the factory installed magazine catch bar” and then installing “a magazine catch bar.” From this, the district the court concluded that the magazine catch bar that is installed must be “separate and distinct from the factory-installed magazine catch bar”; otherwise, “factory-installed” would be superfluous. Because a term that appears in multiple claims should be given the same meaning in all those claims, the court held that the term “magazine catch bar” in claims 1 and 8 similarly must exclude a factory-installed magazine catch bar. This claim construction precluded literal infringement because Juggernaut’s products use the factory-installed magazine catch bar. The court also determined that Juggernaut does not infringe under the doctrine of equivalents.

The Federal Circuit noted that the principle that the same phrase in different claims of the same patent should have the same meaning is a strong one, overcome only if it is clear that the same phrase has different meanings in different claims. The Federal Circuit noted that while claim 15 was directed to a method, claims 1 and 8 claimed a firearm and a device, respectively. The Federal Circuit said that nothing in the language of claims 1 and 8 limits the scope of the generic term “magazine catch bar” to exclude one that was factory installed—specifically, as Juggernaut asserts, factory installed as part of an original

firearm with a detachable magazine.

The Federal Circuit said that Juggernaut was correct that the meaning of the term in claims 1 and 8 could well be informed by a meaning of the term made sufficiently clear in claim 15, but Juggernaut was incorrect that the use of “magazine catch bar” in claim 15 narrows the meaning of the term to support the

urged exclusion of factory-installed magazine catch bars. The Federal Circuit agreed that claim 15 required removing a factory installed magazine catch but it did not require discarding that catch bar, or installing a different catch bar. The Federal Circuit concluded that the specification supports the ordinary-meaning interpretation of “magazine catch bar.” The Federal Circuit said the specification nowhere limits the scope of a “magazine catch bar” to exclude factory-installed ones from the assembly that achieves the fixed-magazine goal.

Juggernaut argued that the disclosed embodiments do not illustrate OEM magazine catch bars, but the Federal Circuit said that cannot make a difference in this case. The Federal Circuit has repeatedly held that “it is not enough that the only embodiments, or all of the embodiments, contain a particular limitation to limit claims beyond their plain meaning.” The Federal Circuit thus construe the term “magazine catch bar” according to its ordinary meaning, which includes a factory installed magazine catch bar.

In Novaritis Pharmaceuticals Corp. v. Accord Healthcare, Inc., [2021-1070](January 3, 2021) the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s determination that U.S. Patent No. 9,187,405 on a treatment for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (“RRMS”), is not invalid and that HEC’s Abbreviated New Drug Application infringes.

The’405 patent claimed a daily dosage of fingolimod “absent an immediately preceding loading dose,” which HEC challenged as lacking written description. The district court found sufficient written description in the EAE model and the Prophetic Trial, neither of which recited a loading dose.

On appeal, HEC attacked the expert testimony underlying the district court’s determination that the EAE experiment describes a 0.5 mg daily human dose as “undisclosed mathematical sleights of hand.” The Federal Circuit disagreed, noting a disclosure need not recite the claimed invention in haec verba. The disclosure need only clearly allow persons of ordinary skill in the art to recognize that the inventor invented what is claimed. The Federal Circuit said that to accept HEC’s argument would require it to ignore the perspective of the person of ordinary skill in the art and require literal description of every limitation, in violation of our precedent. The Federal Circuit found no clear error in the

district court’s reliance on expert testimony in finding description of the 0.5 mg daily human dose in the EAE experiment results.

The Federal Circuit also rejected HEC’s challenge to the negative limitation “absent an immediately preceding loading dose.” The Federal Circuit began by noting that it was well established that there is no “new and heightened standard for negative claim limitations.” Inphi Corp. v. Netlist, Inc., 805 F.3d 1350, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The Court said that negative claim limitations are adequately supported when the specification describes a reason to exclude the relevant limitation. Adding that a specification that describes a reason to exclude the relevant negative limitation is but one way in which the written description requirement may be met. The Federal Circuit said that the written description requirement

is satisfied where the essence of the original disclosure conveys the necessary information—regardless

of how it conveys such information, and regardless of whether the disclosure’s words are open to different interpretations.

The Federal Circuit pointed to expert testimony that one of ordinary skill in the art would understand the examples to exclude a loading does, so the specification’s apparent silence provided adequate written description of the negative limitation. The Court concluded that written description in this case, as in all cases, is a factual issue. In deciding that the district court did not clearly err in finding written description for the negative limitation in the ’405 patent, the court said that it was not establishing a new legal

standard that silence is disclosure. The Federal Circuit said that it was merely holding that on the record before it, the district court did not clearly err in finding that a skilled artisan would read the ’405 patent’s disclosure to describe the “absent an immediately preceding loading dose” negative limitation.

In Intel Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., [2020-1664] (December 28, 2021), the Federal Circuit affirmed the final written decision of the originally challenged claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,229,043, but vacated and remanded as to the substitute claims.

The Federal Circuit addressed first considered the phrase “radio frequency input signal” in ’043 patent claims 17, 19, and 21. Intel argued that the term should be given its ordinary meaning, while Qualcomm argued for a more specific construction. The Federal Circuit noted that ‘[e]ven without considering the surrounding claim language or the rest of the patent document, . . .it is not always appropriate to break down a phrase and give it an interpretation that is merely the sum of its parts.” The Federal Circuit said that the surrounding language points in favor of Qualcomm’s construction, adopted by the Board. The Federal Circuit said the linguistic clues suggested that “radio frequency input signal,” to the relevant audience, refers to the signal entering the device as a whole, not (as Intel proposes) to any radio frequency signal entering any component. The Federal Circuit said that the specification provides further support for the Board’s reading.

The Federal Circuit concluded that in sum, while Intel’s interpretation may have superficial appeal, Qualcomm’s better reflects the usage of “radio frequency input signal” in the intrinsic record, and affirmed it.

On the question of obviousness, the Federal Circuit concluded that substantial evidence does not

support the Board’s determination that a skilled artisan would have lacked reason to combine the prior art to achieve substitute claims 27, 28, and 31. The Federal Circuit rejected the Board’s rationale for determining that it would not have been obvious to combine the references. The Federal Circuit noted that a rationale is not inherently suspect merely because it’s generic in the sense of having broad applicability or appeal.

Merry Christmas, and warm wishes that you can celebrate safely and happily with your friends and family, Celebrating Christmas is a long standing tradition, and the U.S. patent collection documents a steady stream of inventive effort to make Christmas happier and safer. Once of the earliest references to Chistmas in the patent collection is this patent from 1867 on a candllestick for a Christmas tree:

A few years later, an improved Candle Holder was patented with a more patriotic bent:

The fascination with open flames continued, and later that same year, a patent issued on a candle-powered Rotating Christmas Tree:

By 1872, someone finally came up with the idea of at least enclosing the flame in a Wax-Lantern, no doubt saving many trees (and Christmases):

However, candles remained in use and efforts continued to improve them in the 1870’s and 1880’s:

It wasn’t until 1891, when its was proposed to apply electric lighting to Christmas trees:

Best wishes to all for a happy holiday season, and an innovative 2022.

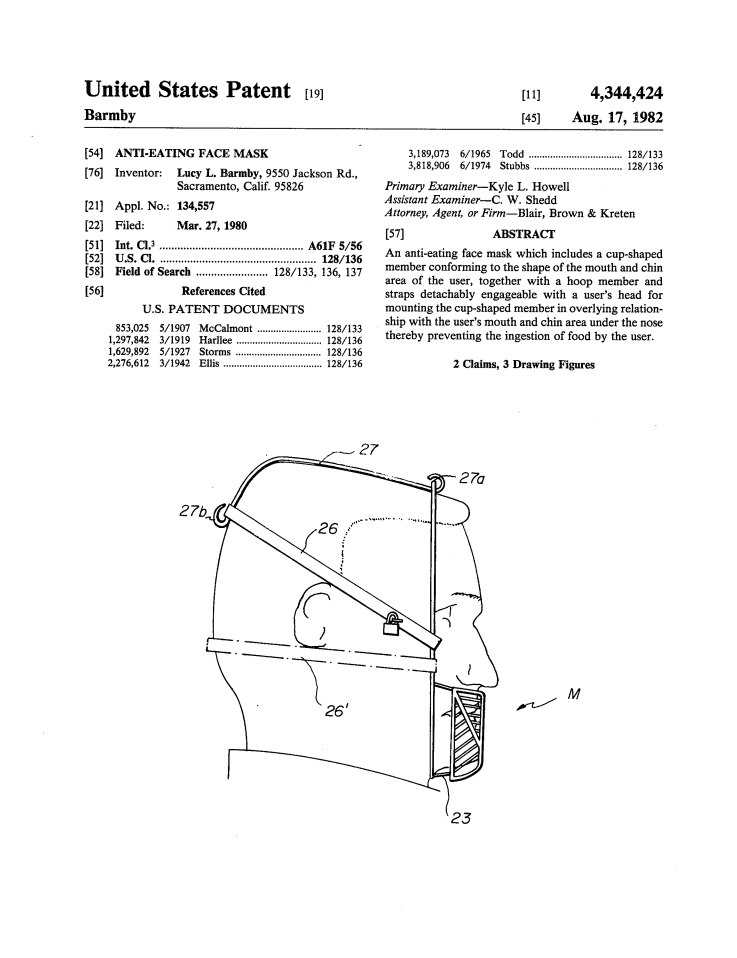

The patent collection is an underused resource for solutions, and yes, it contains a solution to the biggest problem of the day. Back in 1980, Lucy Barmby invented a solution to overeating on Thanksgiving (and every other day):

Lucy may have solved the problem of turkey and pecan pie, but it looks as if gravy is still a threat. Beware, and have a happy holiday with family and friends.