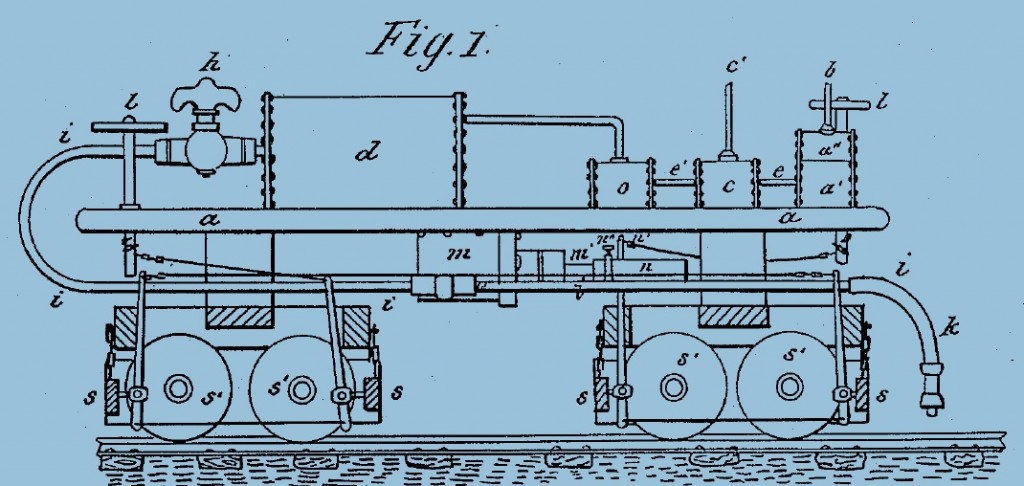

On April 16, 1935, U.S. Patent No. 1,997,901 issued to Orton H. Englehart on a Water Sprinkler — the familiar rotary impact sprinkler.

Monthly Archives: April 2016

April 15 Patent of the Day

April 14 Patent of the Day

On April 14, 1896, U.S. Patent No. 558,393 issued to John Harvey Kellogg on Flaked Cereals and Process of Preparing Same.

April 13 Patent of the Day

April 12 Patent of the Day

April 11 Patent of the Day

April 10 Patent of the Day

April 9 Patent of the Day

Discoveries Are Not Patentable.

In Genetic Technologies Limited v. Merial LLC. [2015-1202, -1203] (April 8, 2016) the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court dismissal for failure to state a claim and entry of final judgment that claims 1–25 and 33–36 of U.S. Patent No. 5,612,179 are ineligible for patenting under 35 U.S.C. §101. The method of the ‘179 patent involved looking in the introns or non-coding regions (aka the junk DNA) for alleles in the exons or coding regions. No one had previously appreciated that alleles in the exons could be identified by looking in the introns.

The Federal Circuit began by noting that it has repeatedly recognized that in many cases it is possible and proper to determine patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 on a Rule 12(b)(6) motion. The Federal Circuit added that In many cases evaluation of a patent claim’s subject matter eligibility under §101 can proceed even before a formal claim construction, quoting: “[C]laim construction is not an inviolable prerequisite to a

validity determination under §101.” The Federal Circuit concluded Here, there is no claim construction dispute relevant to the eligibility issue.

Beginning with Step 1 of the Mayo/Alice test, the Federal Circuit found that the claims were directed to to the relationship between non-coding and coding sequences in linkage disequilibrium and the tendency of such non-coding DNA sequences to be representative of the linked coding sequences which it characterized as a law of nature. The Court explained the claimed invention: a method of detecting a coding region of a person’s genome by amplifying and analyzing a linked non-coding region of that person’s genome. The Court observed that the claim was broad, covering any comparison, for any purpose, of any non-coding region sequence known to be linked with a coding region allele at a multi-allelic locus, concludign the claims broadly cover “essentially all applications, via standard experimental techniques, of the law of linkage disequilibrium to the problem of detecting coding sequences of DNA.”

The Federal Circuit found this “quite similar” to the claims invalidated in Mayo itself. The Federal Circuit also found the claims “remarkably similar” to the claims in Ariosa, which were found in step 1 to be directed to unpatentable subject matter. The Court said “[t]he similarity of claim 1 to the claims evaluated in Mayo and Ariosa requires the conclusion that claim 1 is directed to a law of nature.

At step two of Mayo/Alice the Federal Circuit examined the elements of the claim to determine whether it contains an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed

abstract idea or law of nature into a patent-eligible application. The Federal Circuit concluded that the additional elements of claim 1 are insufficient to provide the inventive concept necessary to render the claim patent-eligible. The Federal Circuit found the added physical steps of DNA amplification and analysis of the amplified DNA to provide a user with the sequence of the non-coding region do not, individually or in combination, provide sufficient inventive concept to render claim 1 patent eligible. A result the Court found directly comparable to Ariosa. The Federal Circuit was not impressed that the analysis was performed on amplified, i.e. manmade DNA, because it was the genetic sequence that was important, and it was identical, Finally the Federal Circuit was not impressed that no one had befor analyzed man-made non-coding DNA in order to detal a coding region allele, finding that “to detect the allele” was a mental process step of the type discounted in Mayo.

The Mayo/Alice two step completely discounts new, and even surprising discoveries of natural phenomenon, in considering whether there is patentable subject matter. This makes unpatentable many important diagnostic advances as in Ariosa and now in Genetic Technologies. The more appropriate question is, once the naturally occurring phenomenon is known, is particular application of that phenomenon obvious. Maybe the results would be similar, but important, valuable advances would not simply be discounted as they are under the current Mayo/Alice test.

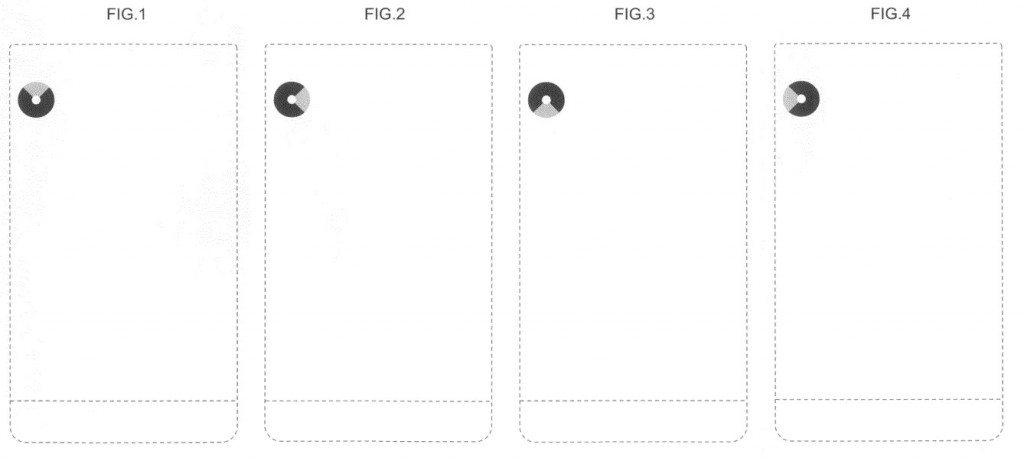

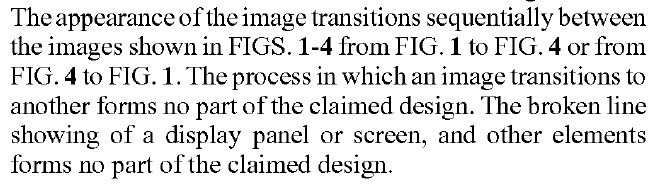

An Animated Review of Design Patents

Design patents protect the appearance of articles of manufacture, and this includes articles of manufacture whose appearance changes over time. In particular, animated displays on computers and other electronic devices can be protected with a design patent. The drawings of are a series of still images of the animated design, showing the progression, somewhat like a “flip book.” Thus, U.S. Patent No. D698,363 protects a spinning design by showing for sequential images:

The patent explains:

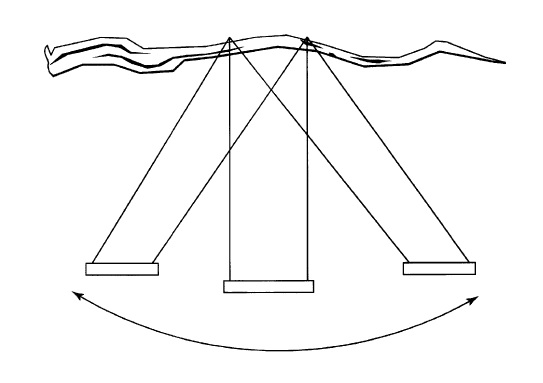

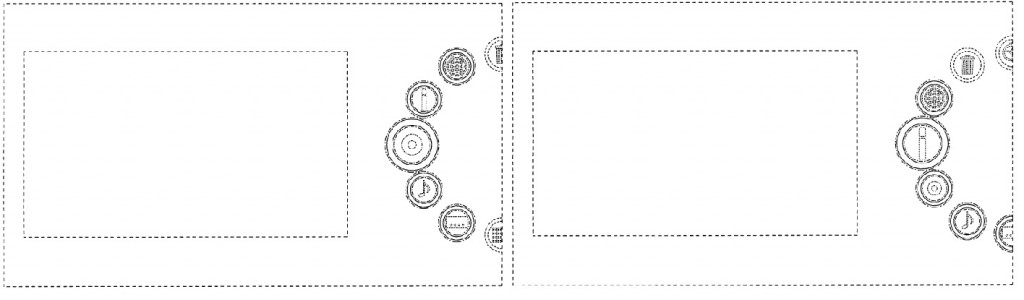

U.S. Patent No. D706,806 shows another on-screen animation in two figures:

The patent explains:

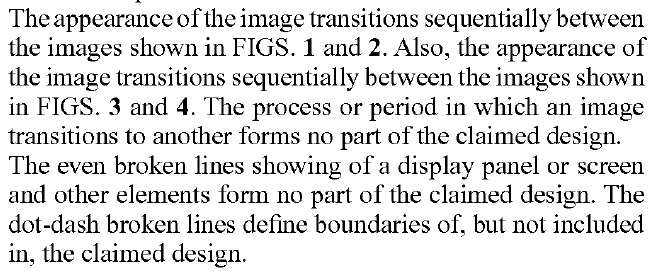

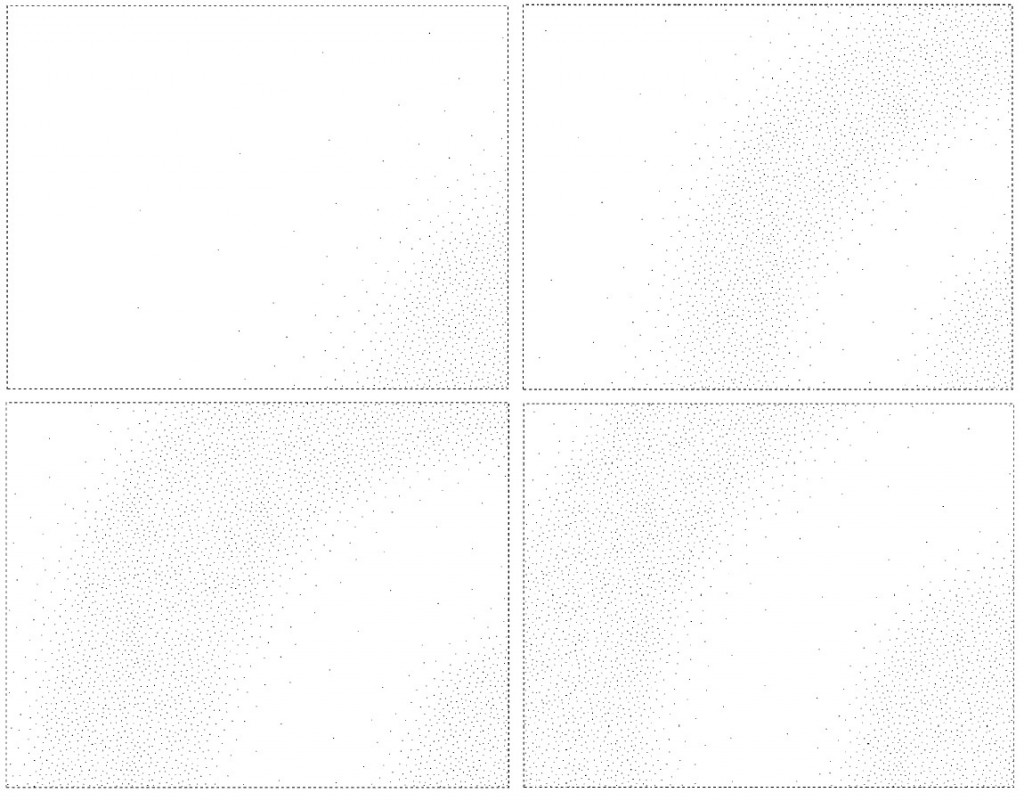

U.S. Patent No. D612,861 shows an animated screen transition over seven images, four of which are shown below:

The patent describes the figures: