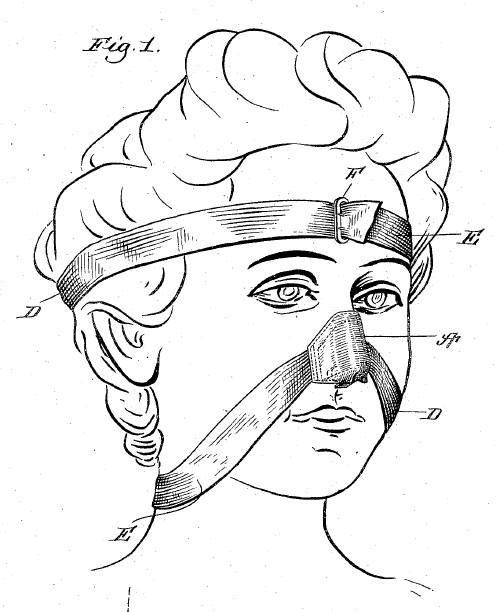

On April 23, 1907, U.S. Patent No. 850978 issued to Ignatius Soares on a Nose Shaper. Fortunately for plastic surgeons everywhere, Ignatius’ invention never caught on, because the user sure looks delighted.

Monthly Archives: April 2016

An Infringement, Divided, May Stand After All

In Mankes v. Vivid Seats Ltd., [2015-1500, 2015-1501, 2015-1909] (April 22, 2016), the Federal Circuit vacated judgment on the pleadings against Mankes, and remanded for further proceedings in light of Akamai IV.

The case involved U.S. Patent No. 6,477,503 on methods for managing a reservation system that divides inventory between a local server and a remote Internet server. It was stipulated that no none person performed all of the steps of any single claim of the patent. However, the defendants; arguments of non-infringement, and the district court’s determination were before the most rececent version of Akamai (Akamai IV). The Federal Circuit said that:

“We need not say how much broadening occurred in Akamai IV. In the present cases, the district court’s rulings and the arguments of Fandango and Vivid Seats to the district court were squarely based on the earlier, narrower standard.”

The Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the case, and rejected defendants’ appeal of the denial of attorneys fees for good measure.

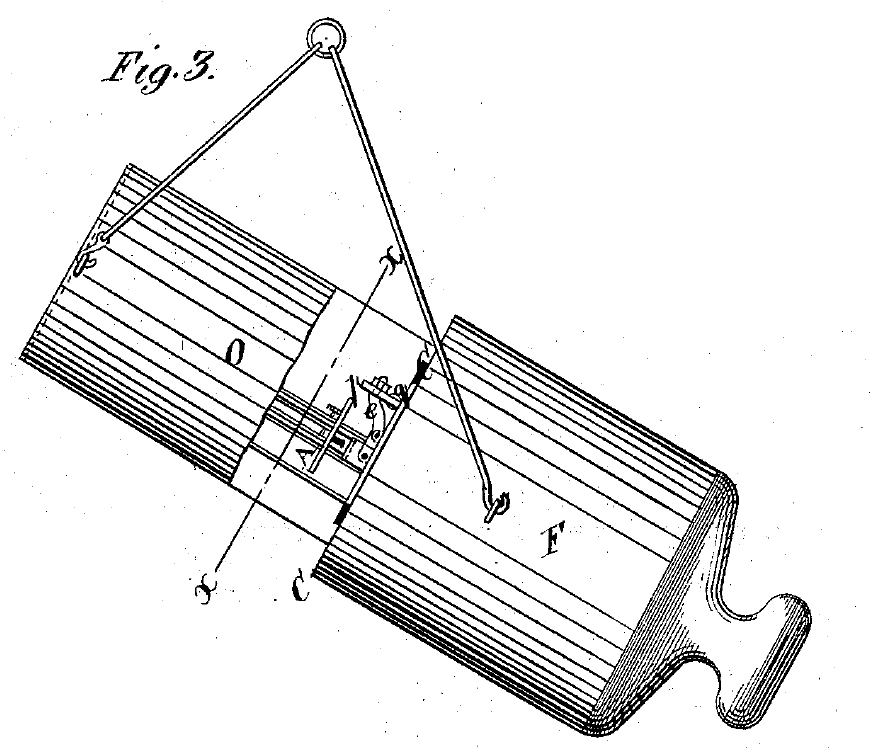

April 22 Patent of the Day

April 21 Patent of the Day

April 20 Patent of the Day

It is Error to Ignore Functional Structures Entirely in a Design Patent Construction

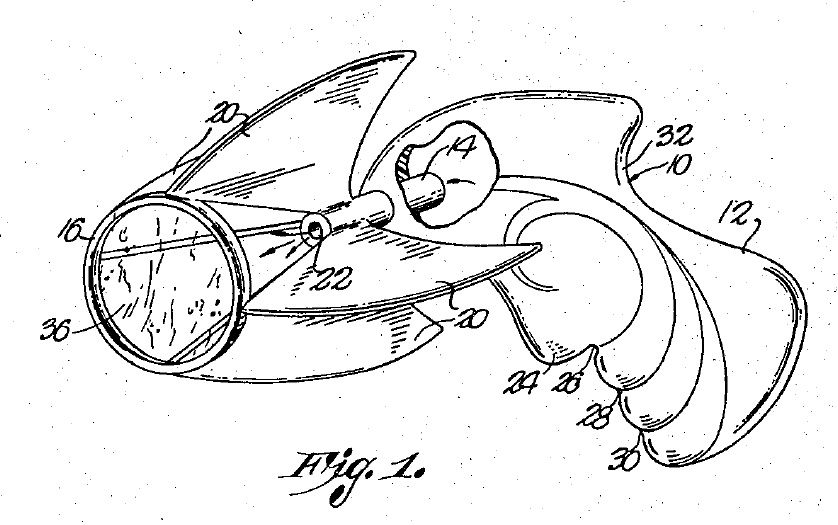

In Sport Dimension, Inc. v. The Coleman Company, [2015-1553] (April 19. 2016) the Federal Circuit vacated the stipulated judgment of non-infringement of U.S. Patent No. D623,714 on a personal flotation device, and remanded for further proceedings consistent with the correct claim construction.

The district court adopted Sport Dimension’s proposed claim construction:

The ornamental design for a personal flotation device, as shown and described in Figures 1–8, except the left and right armband, and the side torso tapering, which are functional and not ornamental.

This construction eliminates several features of Coleman’s claimed design, specifically the armbands and the side torso tapering. The Federal Circuit observed that “[w]ords cannot easily describe ornamental designs.” The Federal Circuit said that a design patent’s claim is thus often better represented by illustrations than a written claim construction, and that a detailed verbal claim constructions increases “the risk of placing undue emphasis on particular features of the design and the risk that a finder of fact will focus on each individual described feature in the verbal description rather than on the design as a whole.

However the Federal Circuit has often “blessed “claim constructions that helped the fact finder distinguish between those features of the claimed design that are ornamental and those that are purely functional, because where a design contains both functional and nonfunctional elements, the scope of the claim must be construed in order to identify the non-functional aspects of the design as shown in the patent.

In OddzOn, Richardson, and Ethicon, the Federal Circuit construed design patent claims so as to assist a finder of fact in distinguishing between functional and ornamental features, but in no case did it entirely eliminate a structural element from the claimed ornamental design, even though that element also served a functional purpose. Even though the Federal Circuit agreed that certain elements of the design serve a useful purpose, it rejected the district court’s ultimate claim construction because it eliminated the functions structures from the claim entirely.

The Federal Circuit said that because of the design’s many functional elements and its minimal ornamentation, the overall claim scope of the claim is accordingly narrow. However the Federal Circuit offered no further guidance on the proper construction.

April 19 Patent of the Day

It’s Not the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation, but the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation in Light of the Specification

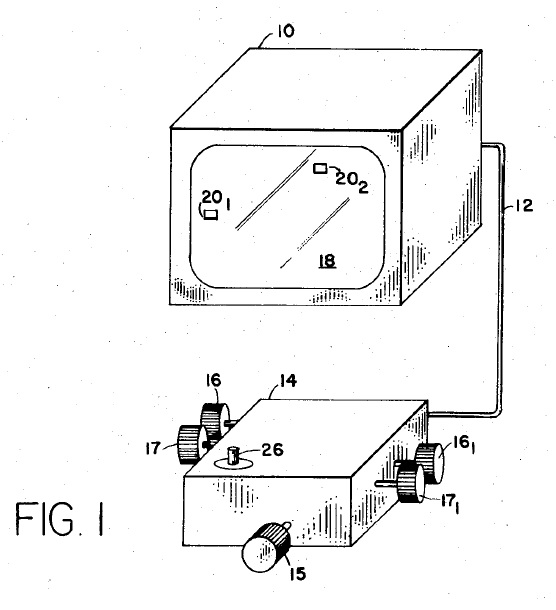

In In re Man Machine Interface Tech. LLC, [2015-1562] (April 19, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed-in-part, reversed-in-part, vacated-in-part, and remanded the PTAB’s affirmance of the rejection of claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,069,614 in ex parte reexamination.

The patent is directed to a remote control device for making selections on television or computer screens. The examiner construed the claim term “adapted to be held by the human hand” in the patent broadly to include various “forms of grasp or grasping by a user’s hand,” such as the grasping of the mouse on a desk top. The examiner similarly interpreted the claim term “thumb switch” as “merely requir[ing] that a switch . . . be capable of being enabled/activated by a thumb but . . . not preclud[ing] another digit, i.e. index finger.” Based upon these broad constructions, the reexamination examiner found the claims anticipated. The PTAB affirmed emphasizing that appellant had not cited to a definition of ‘a body adapted to be held by the human hand’ or ‘thumb switch’ in the Specification that would preclude the Examiner’s broader reading.

The Federal circuit found that the intrinsic record fully determines the proper construction, so its review was de novo. Noting that in reexamination the Board must give the terms their broadest reasonable construction, this construction cannot be divorced from the specification and the record evidence.

The Federal Circuit said that the phrase “adapted to” generally means “made to,” “designed to,” or “configured to,” though it can also be used more broadly to mean “capable of” or “suitable for.” The Federal Circuit found that “adapted to,” as used in the ’614 claims and specification, has the narrower meaning — that the claimed remote control device is made or designed to be held in the human hand and the thumb switch is made or designed for activation by a human thumb.

The Federal Circuit found support for this in the written description, including an express distinction between the claimed device and the deskbound devices in the applied prior art. The Federal Circuit said: “The broadest reasonable interpretation of a claim term cannot be so broad as to include a configuration expressly disclaimed in the specification.” Based upon the language of the specification, the Federal Circuit rejected the Board’s unreasonably broad construction and construe “adapted to be held by the human hand” to mean “designed or made to be held by the human hand,” which it said excluded the desk-bound mouse of the prior art.

Similarly the Federal Circuit rejected the Board’s overly broad construction of “thumb switch being adapted for activation by the human thumb,” noting that the construction ignores the term “thumb” in “thumb switch., or in light of the specification. The Federal Circuit reminded that the proper BRI construction is not just the broadest construction, but rather the broadest reasonable construction in light of the specification. A construction that is unreasonably broad and which does not reasonably reflect the plain language and disclosure will not pass muster.

The Federal Circuit said that the Board’s broad construction of “thumb switch being adapted for activation by a human thumb” as being merely capable of activation by a human thumb is unreasonable in view of the specification’s clear teaching that the patentee intended a narrower meaning.

Because the Board’s anticipation rejection was based on erroneous claim constructions and the rejection is not supported under the proper constructions, the finding of anticipate was reversed.

April 18 Patent of the Day

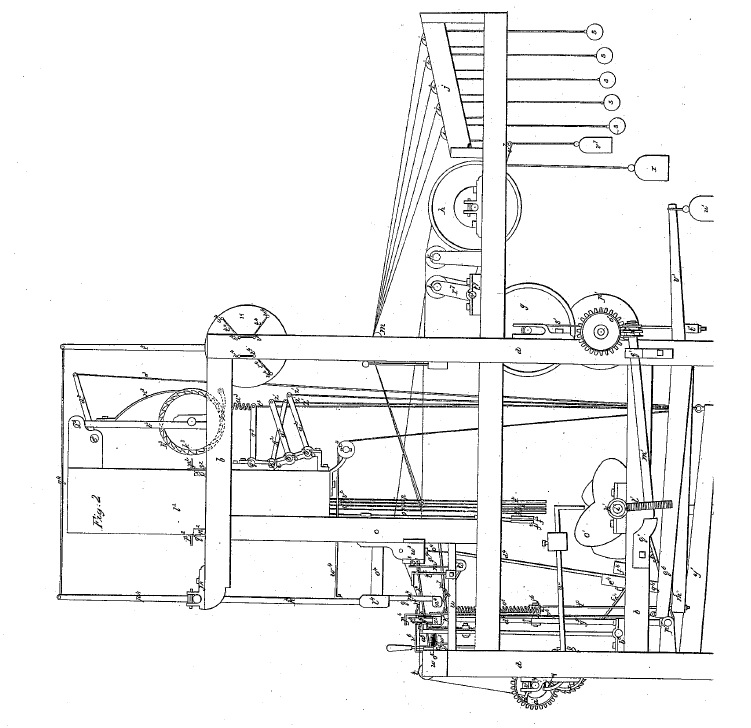

On April 18, 1911, U.S. Patent No. 990,191 issued to Carl Bosch, Ph.D. on a Process of Producing Ammonia.