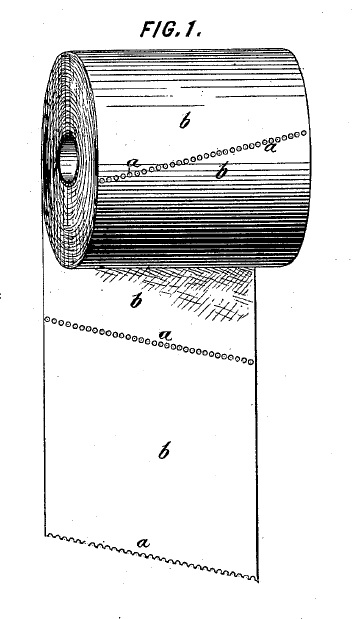

In Bamberg v. Dalvey, [2015-1548] (March 9, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision in an appeal from a consolidated interference proceeding refusing to allow the claims of four patent applications because the specification failed to meet the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112. The involved claims disclose a method for the transfer of printed images onto dark colored textiles by ironing over a specialty transfer paper. The transfer paper generally contains: (1) a removable substrate coated with silicon, (2) a hot-melt adhesive, (3) a white layer, and (4) an ink-receptive layer. During the interference proceeding, Dalvey alleged that Bamberg’s claims were unpatentable for lack of written description, because the claims recite a white layer that melts at a wide range of temperatures, while Bamberg’s specification discloses a white layer that does not melt at ironing temperatures (i.e., below 220°C).

The Federal Circuit agreed that the contested claims are properly construed to encompass a white layer that melts above and below 220°C, and thus Bamberg’s specification must also support a white layer that melts above and below 220°C to satisfy the written description requirement. The Federal Circuit concluded that substantial evidence supports the Board’s determination that Bamberg’s specification fails to meet the written description requirement. Bamberg’s specification stated that the white layer “comprises or is composed of permanently elastic plastics which are non-fusible at ironing temperatures (i.e. up to about 220°C) and which are filled with white pigments—also non-fusible (up to about 220°C),” and that the “elastic plastics must not melt at ironing temperatures in order not to provide with the adhesive layer . . . an undesired mixture with impaired (adhesive and covering) properties.” The Federal Circuit found that Bamberg did not possess a white layer that melts below 220°C because it specifically distinguished white layers that melt below 220°C as producing an “undesired” result. This criticism effectively limited the scope of the disclosure.

In patents, as in life, Mom was right: If you can’t say something nice about the prior art, don’t say anything at all. Otherwise, your criticism may be treated as a disclaimer of claim scope.