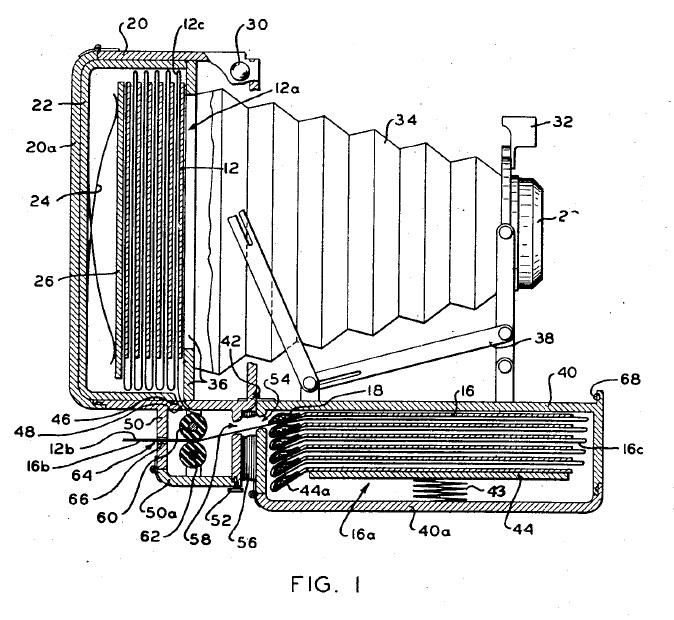

On February 10, 1948, Edwin H. Land was issued U.S. Patent No. 2,435,720 on the Polaroid “Land” Camera.

Once the standard for instant photography, it has been supplanted by digital cameras, and more recently cell phone cameras.

In Rosebud LMS Inc. v. Adobe systems Inc., [2015-1428] (February 9, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed the grant of summary judgment that Adobe Systems Inc. was not liable for pre-issuance damages under 35 U.S.C. §154(d) because it had no actual notice of the published patent application that led to asserted U.S. Patent No. 8,578,280.

35 USC 154(d) provides that:

a patent shall include the right to obtain a reasonable royalty from any person who, during the period beginning on the date of publication of the application for such patent under section 122(b) . . .and ending on the date the patent is issued (A)(i) makes, uses, offers for sale, or sells in the United States the invention as claimed in the published patent application or imports such an invention into the United States; . . . and (B) had actual notice of the published patent application

The Rosebud argued that Adobe had actual notice of its patents because it had previously sued Adobe on the grandparent of the patent in suit, that Adobe followed Rosebud and its product and sought to emulate some of its product’s features; and that it would have been standard practice in the industry for Adobe’s counsel to search for related patents. Adobe, without conceding knowledge, argued that some affirmative action on the part of Rosebud was required to put Adobe on “actual notice” of the patent.

In a case of first impression, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument that some action on the part of patent owner is required for actual notice, but agreed that constructive notice is not sufficient to give “actual notice.” Adobe presented a compelling argument based upon the legislative history of 154(d), but the Fedearl Circuit noted that the language enacted by Congress was not consistent with Adobe’s interpretation. The Federal Circuit also distinguished the interpretation of 287(a) requiring an affirmative act to put an infringer on notice to be entitled to damages, noting the difference in the language of the two sections and noting that Congress could have used similar language in 154(d), but did not.

Noting several good reasons why some affirmative action on the part of the patent owner might make good policy sense, the Federal Circuit invited Congress to amend the statute if it wants a different result.

Even under this lesser standard for actual notice, the Federal Circuit agreed that Rosebud failed to show that Adobe had actual notice of the patent. The Federal Circuit did not find that the earlier litigation on the grandparent of the current patent necessarily put Adobe on notice of the published application, it rejected the argument Adobe “followed” Rosebud and its products, is insufficient, and lastly rejected the argument that Adobe’s outside counsel would have discovered the publication preparing for the earlier litigation, noting that it never reached the claim construction stage because Rosebud missed all of its court-ordered deadlines.

Companies should rethink their competition monitoring programs. Acquiring actual knowledge of a published application increases the company’s exposure to pre-issuance damages. If the company actually uses its knowledge of the published application to reduce its liability — for example by designing around the claims or finding invalidating prior art — then this increased exposure is probably worth it. However, if the knowledge of the published application is not going to be put to good use, the increased exposure comes with no benefit.

,

In Trivascular, Inc., v. Samuels, [2015-1631) (February 5, 2015), the Federal Circuit affirmed a rare PTAB determination in an IPR that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,007,575 were not shown to be invalid. The claims were directed to stents with an inflatable cuff for securing the stent in a blood vessel.

TriVascular argued that the Board erred in construing “circumferential ridges” to mean a “raised strip disposed circumferentially about the outer surface of the inflatable cuff,” contending that it should have been construed to mean “an elevated part of the outer surface disposed about the inflatable cuff that can be either continuous or discontinuous.” The Federal Circuit found that TriVascular’s proposed interpretation was unreasonably broad, and that find the Board’s reliance on the dictionary definition of ridge when considered in the context of the written description and plain language of the claims was proper.

TriVascular further argued that the Board should have applied prosecution history disclaimer, and found that Samuels had disclaimed the narrower construction that the ridges must be continuous. The Federal Circuit said that the same general tenets that apply to prosecution history estoppel apply to prosecution history disclaimer. Both doctrines require that the claims of a patent be interpreted in light of the proceedings in the PTO during the application process. As applied to a disclaimer analysis, “the prosecution history can often inform the meaning of the claim language by demonstrating how the inventor understood the invention.” Disclaimer “ensures that claims are interpreted by reference to those that have been cancelled or rejected, but the party seeking to invoke prosecution history disclaimer bears the burden of proving the existence of a “clear and unmistakable” disclaimer that would have been evident to one skilled in the art.

TriVascular argued that the disclaimer arose when Samuels amended the claims to recite “continuously circumferential ridges,” but the claims that were later allowed did not have this requirement, but instead had other limitations defining over the prior art. However the Federal Circuit did not find this sufficient to work a clear and unmistakable disclaimer.

Regarding obviousness, the Federal Circuit noted that Although the KSR test is flexible, the Board must still be careful not to allow hindsight reconstruction of references without any explanation as to how or why the references would be combined to produce the claimed invention. The Federal Circuit found that the Board’s findings that a skilled artisan would neither have had the motivation to combine nor a reasonable likelihood of success in combining the references were supported by substantial evidence, and supported the Board’s conclusion on nonobviousness.

Finally the Federal Circuit rejected Trivascular’s complaint that the final written decision was inconsistent with the Board’s institution decision. The Federal Circuit commented that this misguided theme pervaded TriVascular’s briefs, and said that contrary to TriVascular’s assertions:

the Board is not bound by any findings made in its Institution Decision. At that point, the Board is considering the matter preliminarily without the benefit of a full record. The Board is free to change its view of the merits after further development of the record, and should do so if convinced its initial inclinations were wrong. To conclude otherwise would collapse these two very different analyses into one, which we decline to do.

The Federal Circuit added that TriVascular’s argument also fails to appreciate that there is a significant difference between a petitioner’s burden to establish a “reasonable likelihood of success” at institution, and actually proving invalidity by a preponderance of the evidence at trial.

A Beauregard claim is a claim to a computer program written as a claim to an article of manufacture: a computer-readable medium on which instructions are encoded for carrying out a process. Beauregard appealed the rejection of his claims directed to software on a tangible storage medium. The Court never approved this method of claiming software, because the Commissioner of Patents conceded that “that computer programs embodied in a tangible medium, such as floppy diskettes, are patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and must be examined under 35 U.S.C. § 102 and 103,” and dismissed the appeal In re Beauregard, 53 F.3d 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

This worked well until In re Nuijten, 500 F.3d 1346 (Fed. Cir. 2007), where the Federal Circuit held that signals were not patent eligible, because their ephemeral nature kept them from falling within the statutory categories of 35 U.S.C. § 101. This undermined Beauregard claims to computer programs electronically distributed. In 2010, the USPTO advised applicants that, to avoid running afoul of In re Nuijten, software claims should be directed to non-transitory computer-readable media.

However, the USPTO’s wording may be problematic, because rewritable storage media such as flash drives, are regarded by at least some as “transitory.” To resolve this potential issue with the USPTO’s non-transitory computer-readable media, it may behoove the applicant to provide an explanation or definition of “non-transitory” that does not exclude legitimate tangible temporary storage media. For example, this language from recently issued U.S. Patent No. 9113131:

Generally speaking, a computer-accessible medium may include any tangible or non-transitory storage media or memory media such as electronic, magnetic, or optical media—e.g., disk or CD/DVD-ROM coupled to computer system 400 via bus 430. The terms “tangible” and “non-transitory,” as used herein, are intended to describe a computer-readable storage medium (or “memory”) excluding propagating electromagnetic signals, but are not intended to otherwise limit the type of physical computer-readable storage device that is encompassed by the phrase computer-readable medium or memory. For instance, the terms “non-transitory computer-readable medium” or “tangible memory” are intended to encompass types of storage devices that do not necessarily store information permanently, including for example, random access memory (RAM). Program instructions and data stored on a tangible computer-accessible storage medium in non-transitory form may further be transmitted by transmission media or signals such as electrical, electromagnetic, or digital signals, which may be conveyed via a communication medium such as a network and/or a wireless link.

U.S. Patent No. 9110963 explains:

The terms “tangible” and “non-transitory,” as used herein, are intended to describe a computer-readable storage medium (or “memory”) excluding propagating electromagnetic signals, but are not intended to otherwise limit the type of physical computer-readable storage device that is encompassed by the phrase computer-readable medium or memory. For instance, the terms “non-transitory computer readable medium” or “tangible memory” are intended to encompass types of storage devices that do not necessarily store information permanently, including for example, random access memory (RAM). Program instructions and data stored on a tangible computer-accessible storage medium in non-transitory form may further be transmitted by transmission media or signals such as electrical, electromagnetic, or digital signals, which may be conveyed via a communication medium such as a network and/or a wireless link.

A simpler explanation is provided in U.S. Patent No. 9148676:

The term “non-transitory”, as used herein, is a limitation of the medium itself (i.e., tangible, not a signal ) as opposed to a limitation on data storage persistency (e.g., RAM vs. ROM).

When claiming software stored on a computer readable medium, explaining the claim terms may be important.