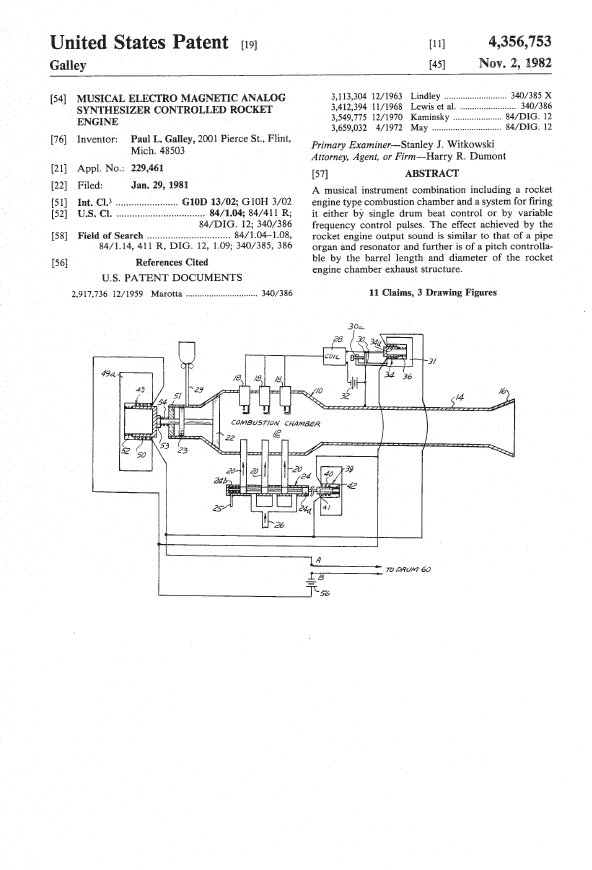

On November 2, 1982, Laul Galley received U.S. Patent No. 4,356,753 on a Musical Electro Magnetic Analog Synthesizer Controlled Rocket Engine. Mr. Galley explained that the effect achieved by the rocket engine output “is similar to that of a pipe organ” and that the pitch can be similarly controlled by “the barrel length and diameter of the rocket engine chamber exhaust structure.”

Category Archives: Patent of the Day

November 1, 2024

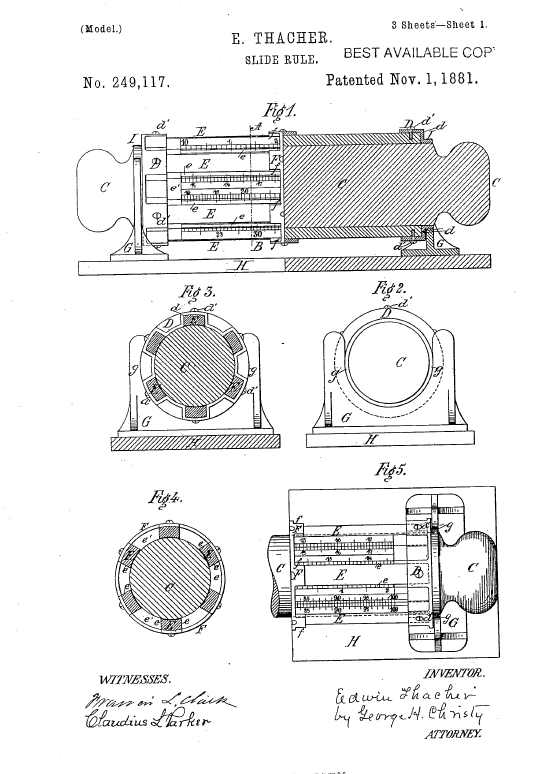

On November 1, 1881, Edwin Thatcher a computing engineer for the Keystone Bridge Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, received U.S. Patent No. 249,117 on an improved slide rule. Thacher was a graduate of Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute and spent much of his career designing railway bridges, inventing his slide rule to assist with his calculations.

The slide rule was invented sometime between 1620 and 1630, shortly after John Napier’s publication of the concept of the logarithm. In 1620 Edmund Gunter of Oxford developed a calculating device with a single logarithmic scale. Two years later in 1622 William Oughtred of Cambridge combined two handheld Gunter rules to make a device that is recognizably the modern slide rule.

Edwin Thatcher’s slide rule is notable for its cylindrical form, although his was not the first slide rule of a cylindrical form factor. Thacher’s rule, though it fit on a desk, was equivalent to a conventional slide rule over 59 feet long. It had scales for multiplication and division and another scale, with divisions twice as large, for use in finding squares and square roots.

October 30, 2024

On October 30, 1888, John J. Loud a patent attorney and occasional inventor received U.S. Patent No. 392,046 on one of the first ball point pens.

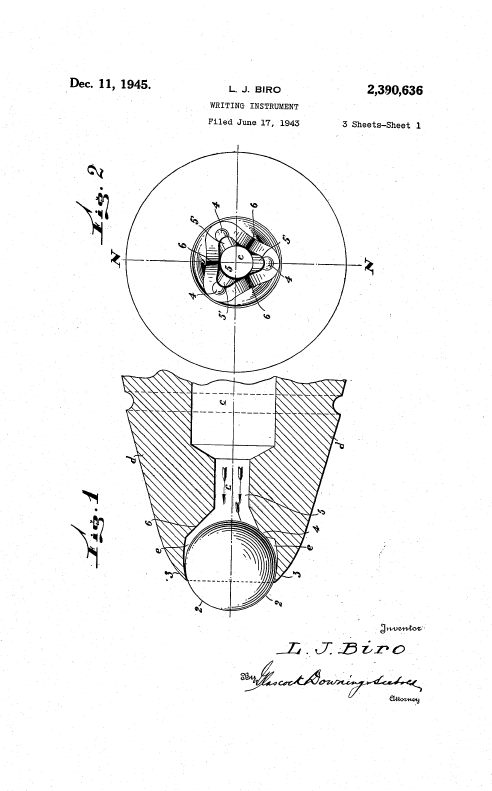

This pen was not a commercial success, but others soon followed. None were very successful until Laszlo Biro’s ball point pen design, which received U.S. Patent No. 2,390,636 in 1945:

Ss influential was Biro’s design, that 79 years later ball point pens are called “Biros” in many parts of the world. In 1945 Milton Reynolds, an American businessman from Chicago, visited Argentina where Biros were being manufactured and bought some of Bíró’s pens. Reynolds returned to the U.S., and changing the design slightly to avoid Biro’s patent, and the “Reynold’s Rocket” went on sale at Gimbels on October 29, 1945. Initial sales were brisque, but ink leaks soon quelled the popularity of the pen.

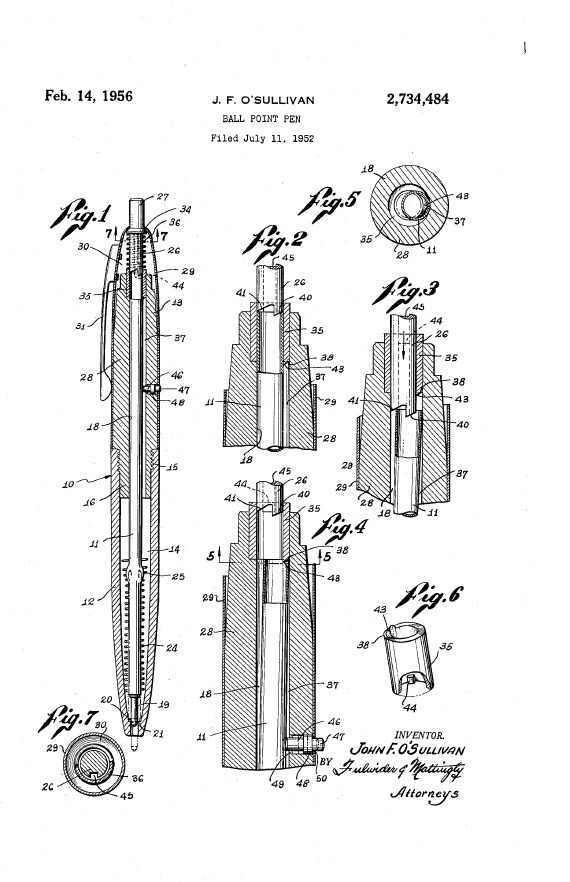

The next big entrant on the ball point pen market was the Frawley Corporation, whose pen received U.S. Patent No. 2,734,484 on February 14, 1956:

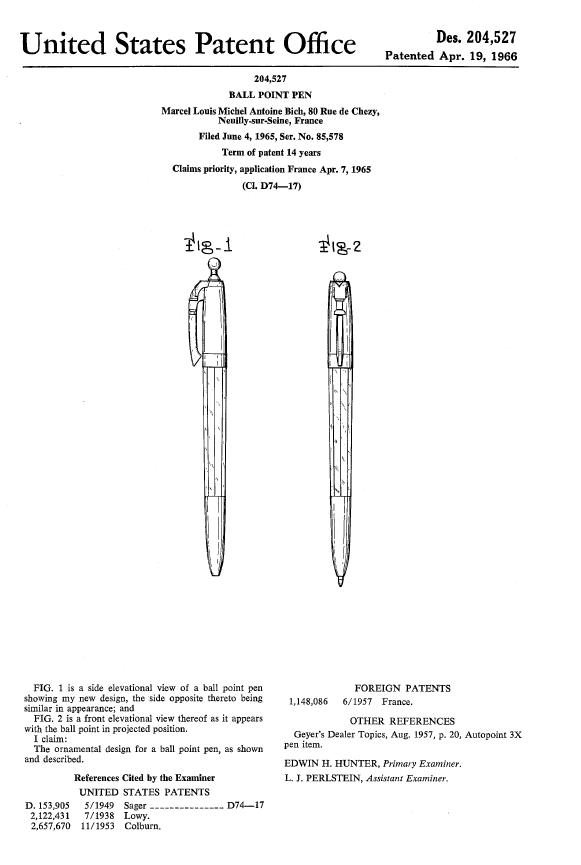

The king of ball point pens, at least in the U.S., was Marcel Louis Michel Antoine Bich, who Bic pens were synonymous with ball point pens in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Bich received two design patents on ball point pen designs U.S. Patent Nos. D2024527 and D218492:

Bich also saw Biro’s pens in Argentina during World War II, and in 1944, licensed Biro’s design. Between 1949 and 1950, Bich’s design team at Société PPA designed the familiar Bic Crystal, which he launched in Europe in in December 1950,and in 1959 brought the pen to the American Market.

IIn September 2006, the Bic Cristal was named the best selling pen in the world after the 100 billionth was sold.

October 29, 2024

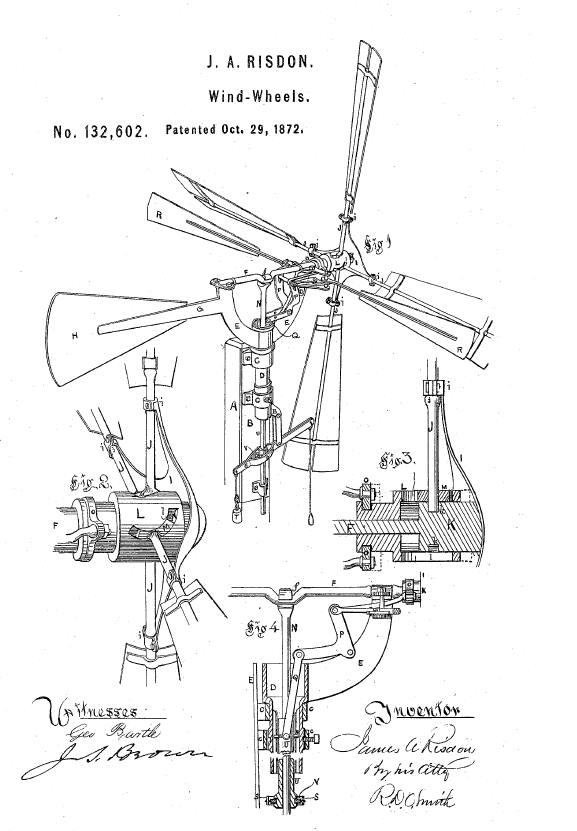

On October 29, 1872, James A. Risdon received U.S. Patent 132,602 on an improved windmill entitled Wind-wheel:

Until the 1870’s windmills were made of wood, the only metal being bolts and other small parts. Risdon’s “Iron Turbine” was the first all metal windwill, and appeared on the market in 1876. A few years later,

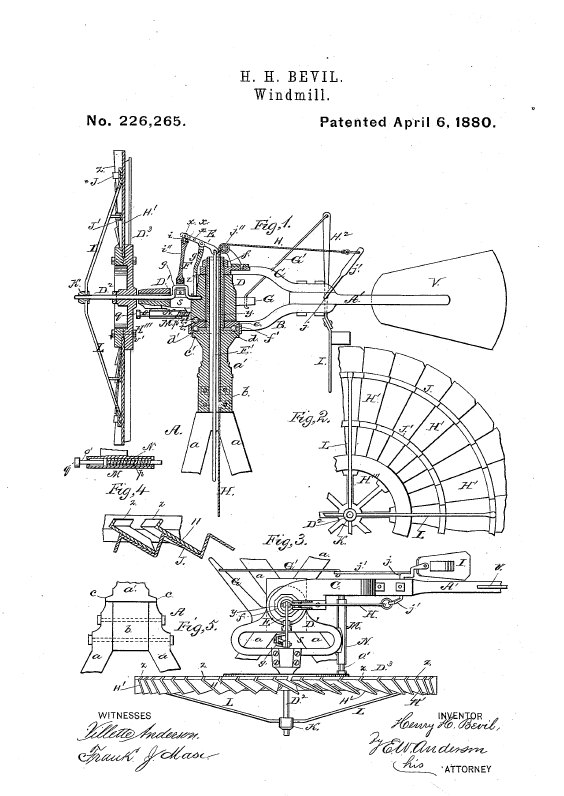

Henry H. Beville, patented (U.S. Patent No. 226265) another all-metal design in 1880:

Beville was a traveling salesman for a farm implement company in Indiana. He licensed the “Iron Duke” for manufacture and sale, making a substantial profit on his invention.

October 28, 2024

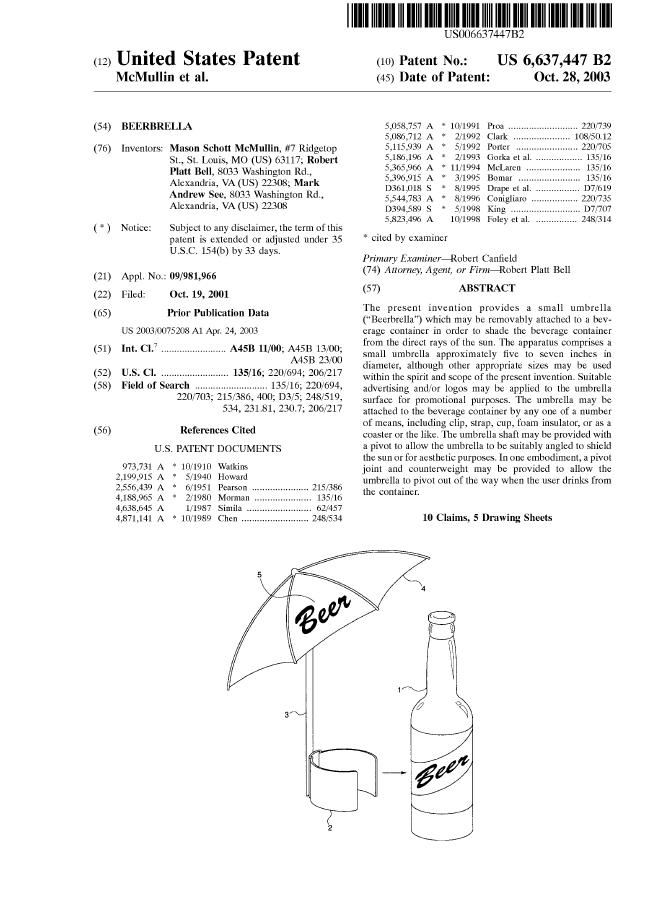

On October 28, 2003, Mason McMullin, Robert Bell, and Mark See obtained U,S, Patent No. 6,637,447 on the BEERBRELLA:

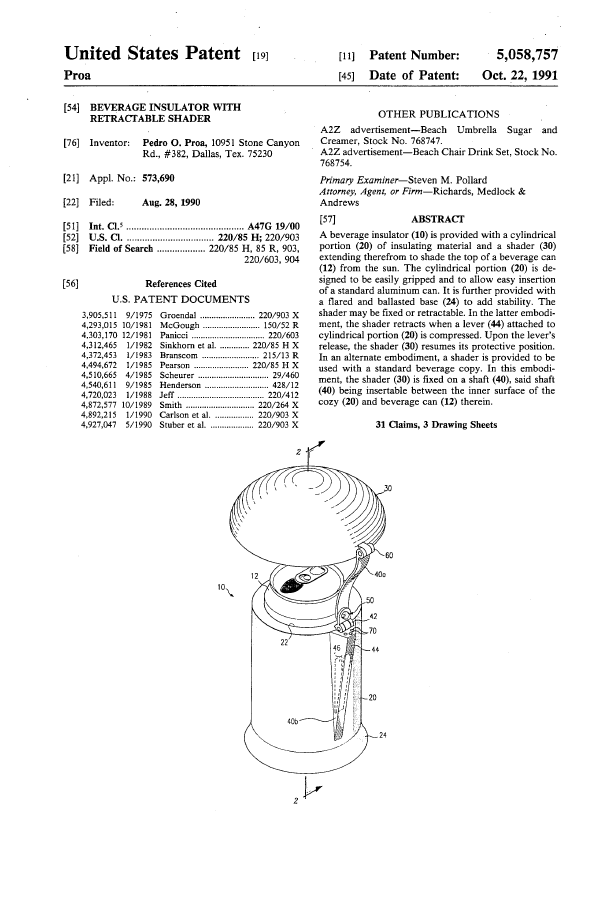

This was not the first attempt to shade a beverage. U.S. Patent No. 5,058,757 is on a Beverage Insulator with Retractable Shader:

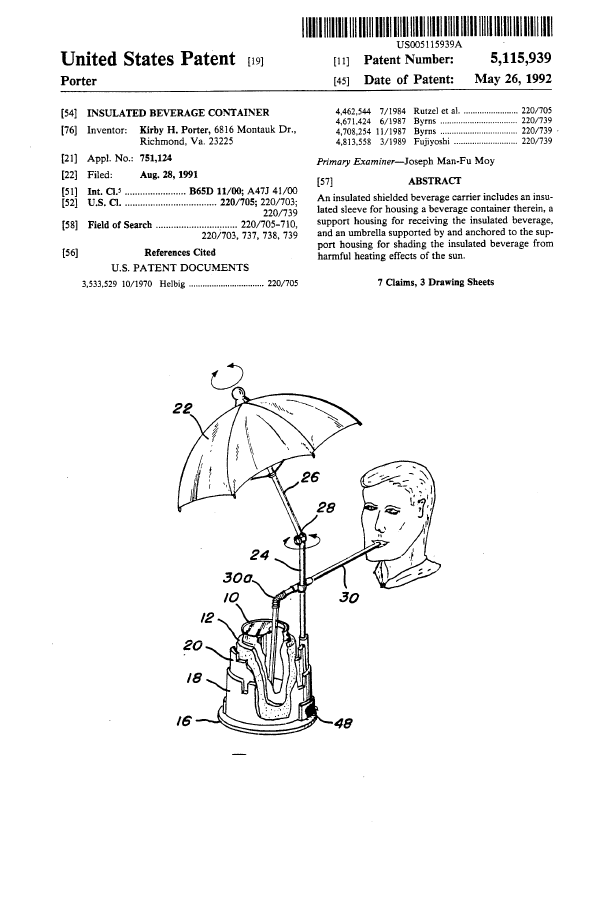

U.S. Patent No. 5,115,939 protects a Insulated Beverage Container that features an umbrella:

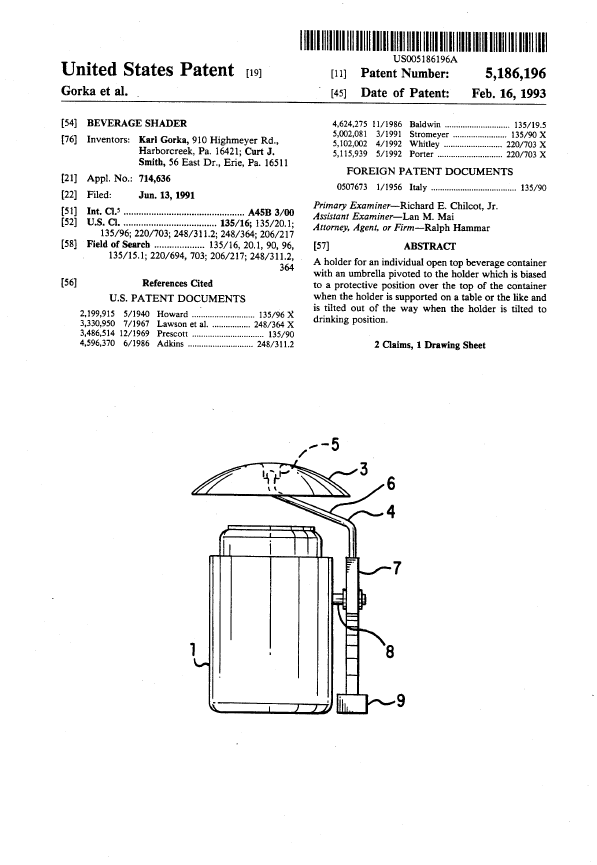

U.S. Patent No. 5,186,196 protects a Beverage Shader with a pivoting umbrella:

October 27, 2024

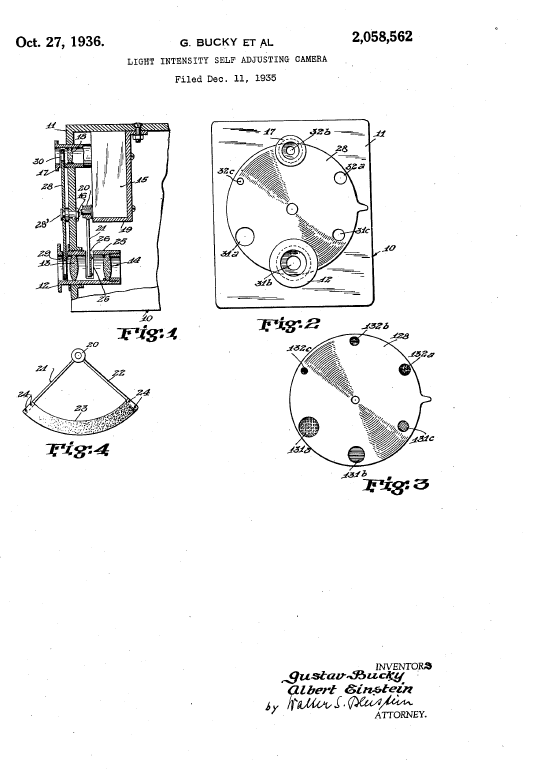

Oon October 27, 1936, Gustav Bucky and Albert Einstein (yes, THAT Albert Einstein) received U.S. Patent No. 2,058,562 on a Light Intensity Self Adjusting Camera:

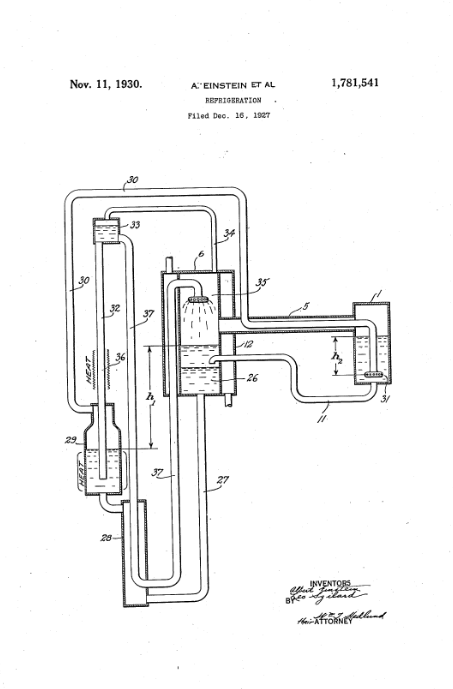

This was not Albert’s first experience with patents. In addition to being a patent examiner in the Swiss Patent Office (imagine trying to convince him that some invention was not obvious), he earlier patented a refrigeration system (U.S. Patent No. 1,781,541, with Leo Szilard:

October 26, 2024

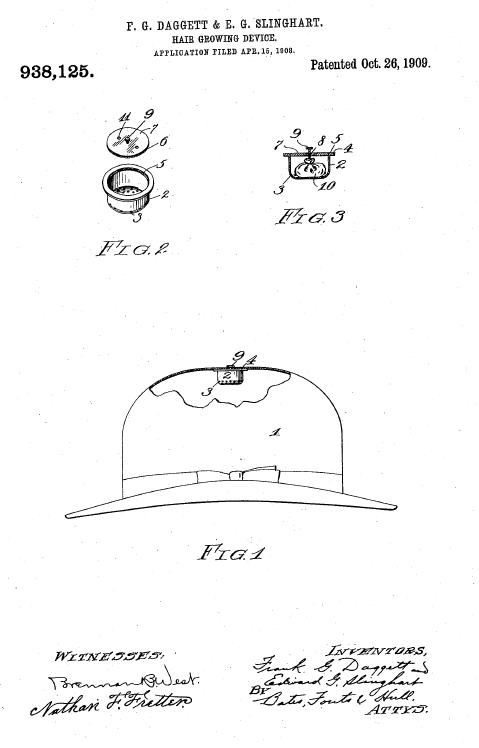

On October 26, 1909, Frank G. Daggett and Edward G. Slinghart received U.S. Patent No. 938125 on a Hair Growing Device:

The patent explains “[a]s is well known, a fruitful source of loss of hair is the lack of ventilation or circulation of air within hats. The warmth of the head soon heats

the air within the hat and the presence of this warm air in contact with the scalp

causes the hair to lose its vitality and to fall out.”

The device comprises comprises “a receptacle having perforations therein and provided with means for attaching the receptacle to the body or crown of the hat, together with a sack or container for material in a dry or powdered form capable, when heated or moistened of evolving oxygen.” “In operation, the warmth and moisture of the head heats and moistens the air confined within the hat and gradually evolves oxygen from the ingredients contained within the sack.”

October 25, 2024

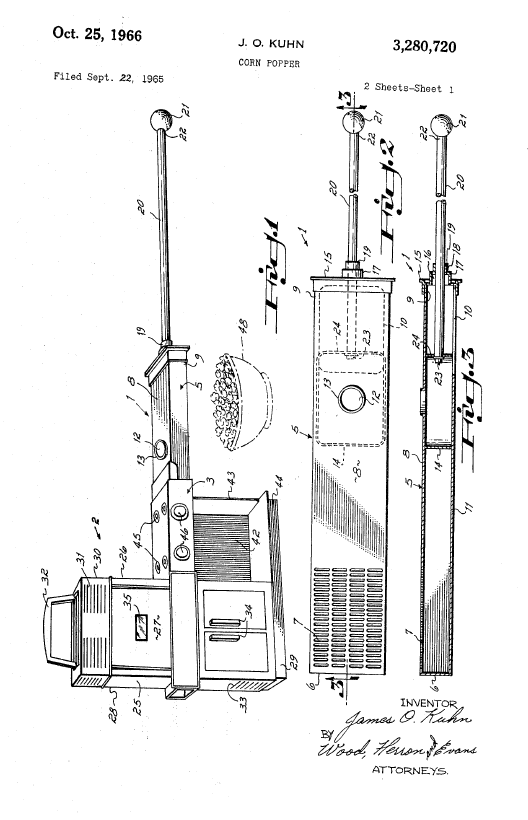

On October 25, 1966, U.S. Patent No. 3,280,710 issued to James O. Kuhn on a Corn Popper.

This corn popper was specially adapted for use with the Easy-Bake Oven that Kuhn also invented:

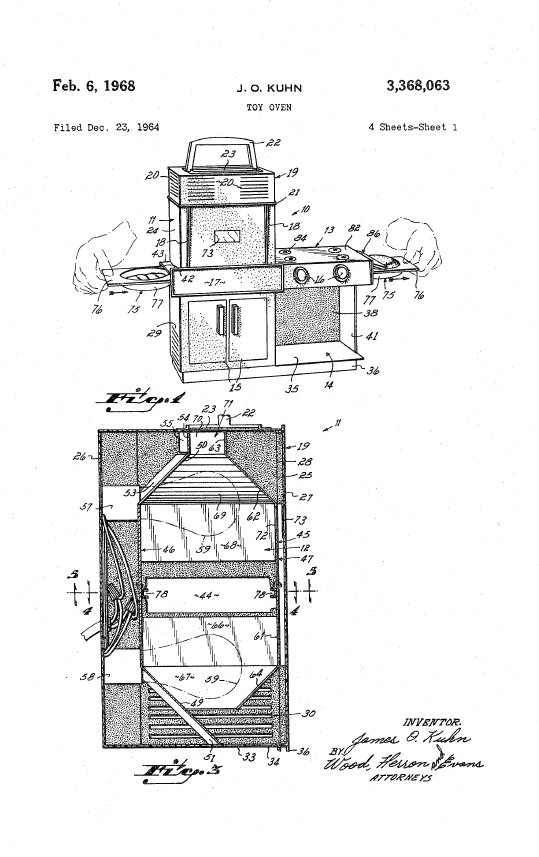

U.S. Patent No. 3,368,063 issued to Kuhn on February 6, 1968, on the Easy Bake Oven itself.

Kenner introduced the Easy Bake Oven on November 4, 1963. Originally available in yellow or turquoise, and powered by two 100 watt lightbulbs. The toy has morphed considerably over the years, with chaging designs and colors. The lightbulb heat source was eliminated in 2011, on fears that incadescent bulbs would become unavailable. The current version of the Easy Bake Oven, sold by Hasbro, resembles a microwave.

The Easy Bake Oven was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in 2006

October 24, 2024

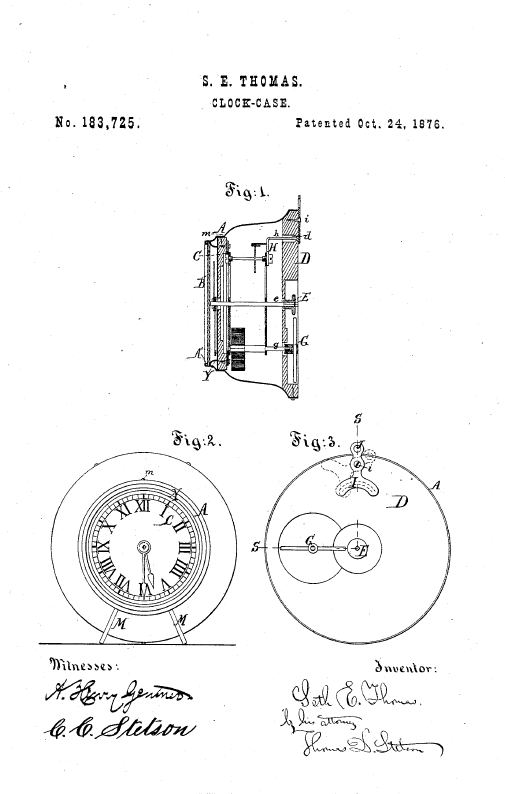

On October 24, 1876, U.S. Patent No. 183725 issued to Seth E. Thomas (son and namesake of the founder of Seth Thomas & Sons clock making enterprise) on an Improvement in Clock-Cases.

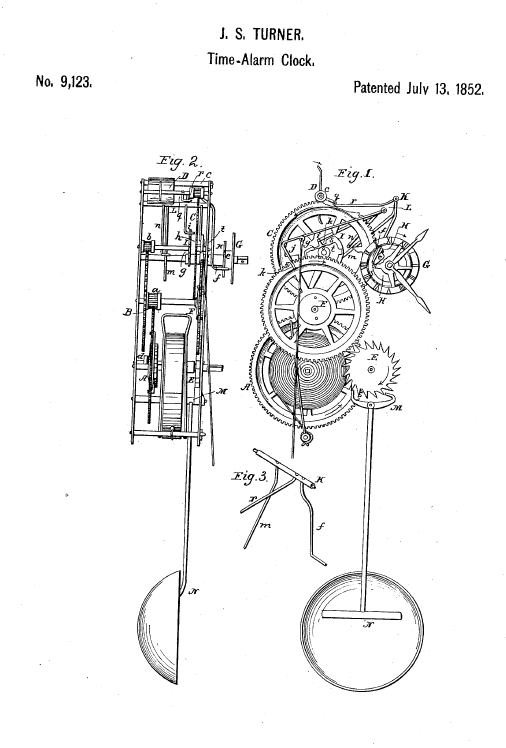

The case was particularly adapted for the now familiar back-winding alarm clock. There were alarm clocks before this (and the patent indicates that “[t]he works need involve no novelty”). Levi Hutchins is credited with one of the first U.S. alarm clocks in 1787. The alarm on this clock had a preset time that could not be changed. U.S. Patent No. X7154 from 1832 on an Alarm Bell, For Time Pieces, Alarm Clock discloses a bell for an alarm clock. U.S. Patent No. 1956 from 1841 mentions the “common alarm clock.” U.S. Patent No. 9123 from 1852 is the first U.S. on an alarm clock per se.

October 23, 2024

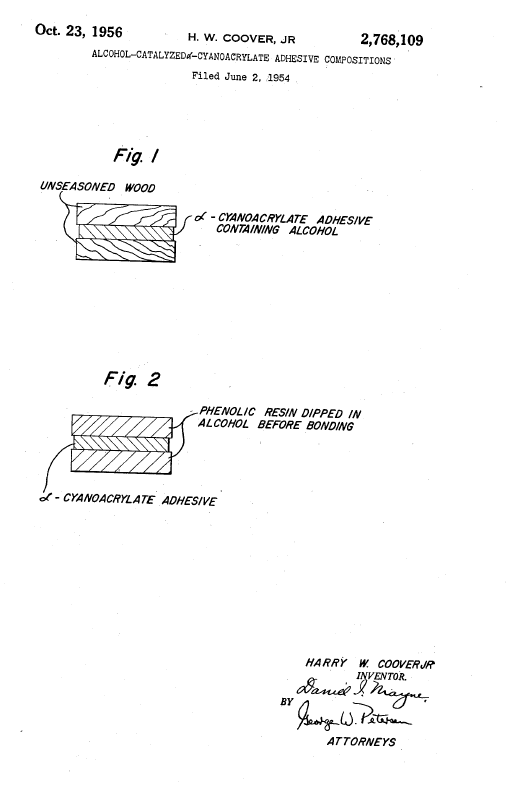

On October 23, 1956, Harry W. Coover, Jr., was awarded U.S. Patent No. 2,768,109, on Alcohol-Catalyzed alpha-Cyanoacrylate Adhesive Compositions:

This patent was assigned to Eastman Kodak Company, which began selling Coover’s adhesive under the brand SUPER GLUE in 1958.

Coover received his B.S. from Hobart College and his M.S. and Ph.D. from Cornell University. Coover, and received more than 460 patents.