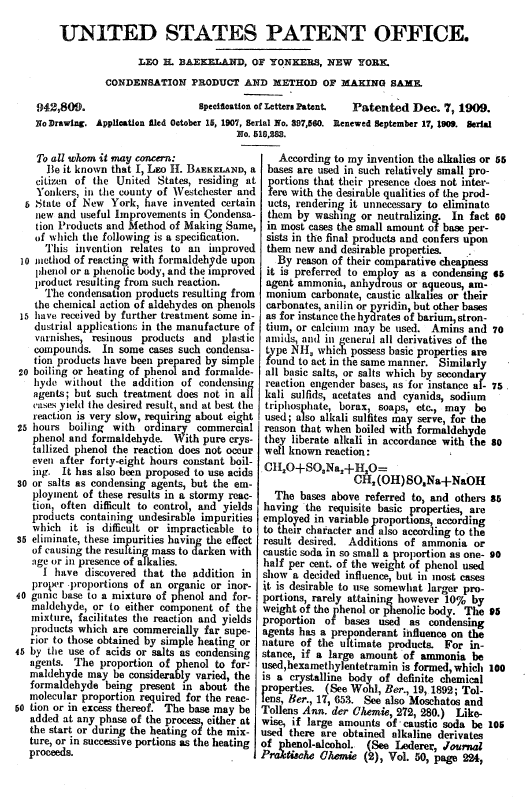

On December 7, 1909, U.S. Patent No. 942,809 issued to Leo Bakeland on a Condensation Product and Method of Making Same:

Bakeland called the product Bakelite, and unlike the plastics before it, Bakelite became instant success, it was cheap to produce, non-flammable, versatile, and could retain its form even when its heated, Bakelite quickly found thousands of applications in products of all kind.

Bakelite was not the first plastic. That honor goes to Parkesine, a celluloid based on nitrocellulose treated with a variety of solvents, created by Alexander Parkes in 1856. Daniel Spill, who worked with Parkes, too over Parkes’ patents, improving the Parkesine, and naming the resulting plastic Xylonite. Businessman John Wesley Hyatt discovered a method to simplify the production of celluloid, making industrial production possible, and founded the Celluloid Manufacturing Company in the US.