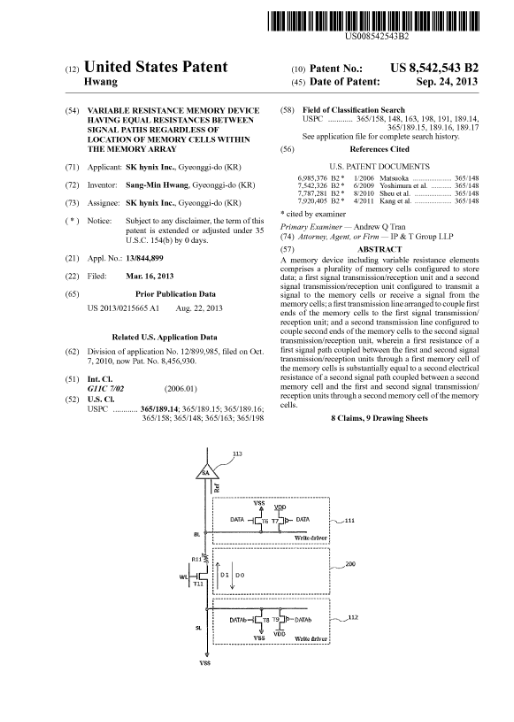

In Alexsam, Inc. v. AETNA, Inc., [2022-2036] (October 8, 2024), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded portions of the district court’s dismissal of AlexSam’s claim for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 6,000,608. The ’608 patent is entitled “Multifunction Card System” is directed to “a debit/credit card capable of performing a plurality of functions” and a “processing center which can manage such a multifunction card system.”

The district court found that AlexSam could not prevail on its claims based on the Mastercard Products because Aetna had an express license via the License Agreement to market those products. The court further concluded that AlexSam failed to state a claim of direct infringement based on the VISA Products because only third-party customers, and not Aetna itself, could have directly infringed. It appeared to the district court that AlexSam’s accusations were largely targeted at Aetna’s subsidiaries, who were not defendants, and that “AlexSam fail[ed] to allege control or direction by Aetna which would warrant disregarding the corporate form.”

On appeal, AlexSam raised two specific challenges to the district court’s conclusions: (i) that Aetna’s Mastercard Products are licensed and, therefore, cannot directly or indirectly infringe claims 32 and 33 of the ’608 patent, and (ii) that it is implausible to believe that Aetna itself “makes” or “uses” the VISA Products.

The Federal Circuit agreed with AlexSam that the district court erred by resolving the Mastercard licensing issues “on the limited information provided” in the Second Amended Complaint, its attachments, and the motion to dismiss briefing. The Federal Circuit said that not only was the scope of the license narrower than the district court seems to have un-derstood, but there were also open issues remaining that need to be resolved before the impact of the license on AlexSam’s allegations can be fully assessed.

On the infringement allegations, the Federal Circuit said the district court erred by concluding that AlexSam failed to allege a plausible claim of direct infringement by Aetna’s making and using the VISA Products. The Federal Circuit said that a plaintiff is not required to plead infringement on an element-by-element basis. Instead, it is enough that a complaint place the alleged infringer on notice of what activity is being accused of infringement.