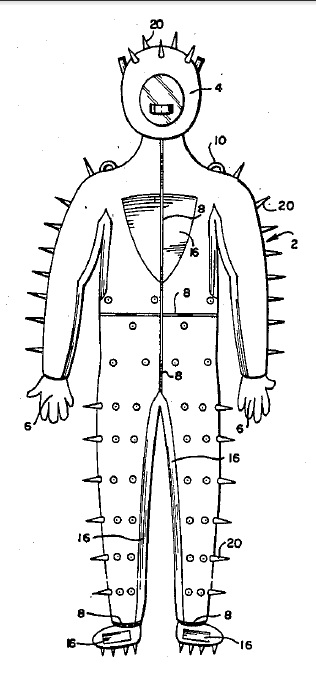

On May 30, 1978, U.S. Patent No. 4,833,729 issued to Nelson C. Fox. Rosetta H.V.G. Fox on Shark Protector Suit.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Jurisdiction Cannot Be Cured Retroactively If Plaintiff Lacked Substantial Rights to Patent When Suit Was Filed

In Diamond Coating Tech. v. Hyundai Motor, [2015-1844, 2015-1861] (May 17, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed the dismissal of a patent infringement action for lack of standing.

The Federal Circuit agreed that Diamond did not possess sufficient rights to make, use, on sell the patented invention, because its assignor Sanyo retained a right and license to make, use, and sell products covered by the patents-in-suit. The assignment and transfer agreement did not even grant Diamond a right to practice the patents, limiting Diamond’s rights to the prosecution, maintenance, licensing, litigation, enforcement, and exploitation of the patents.

The Federal Circuit said that unless Diamond received all substantial rights in the patents-in-suit at the time it filed suit in the District Court, it was not a “patentee,” and it could not bring suit by itself. The Federal Circuit said that Sanyo retained significant control over Diamond’s enforcement and litigation activities, and thus Diamond did not receive all substantial rights.

While Diamond and Sanyo executed nunc pro tunc agreements to purportedly clarify the parties’ original intent, the Federal Circuit held that its precedent (Alps South, LLC v. Ohio Willow Wood Co.) prevented nunc pro tunc assignments from conferring confer retroactive patentee status.

Reflecting on Design Patents

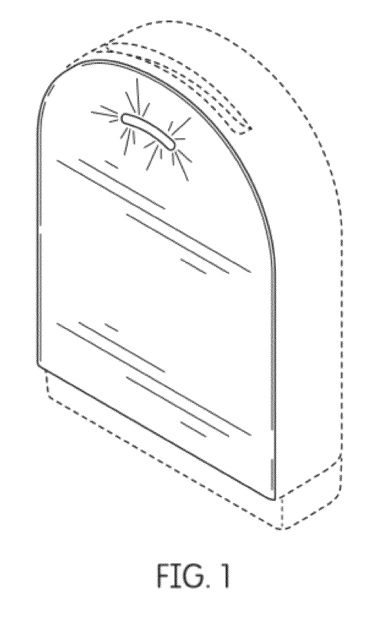

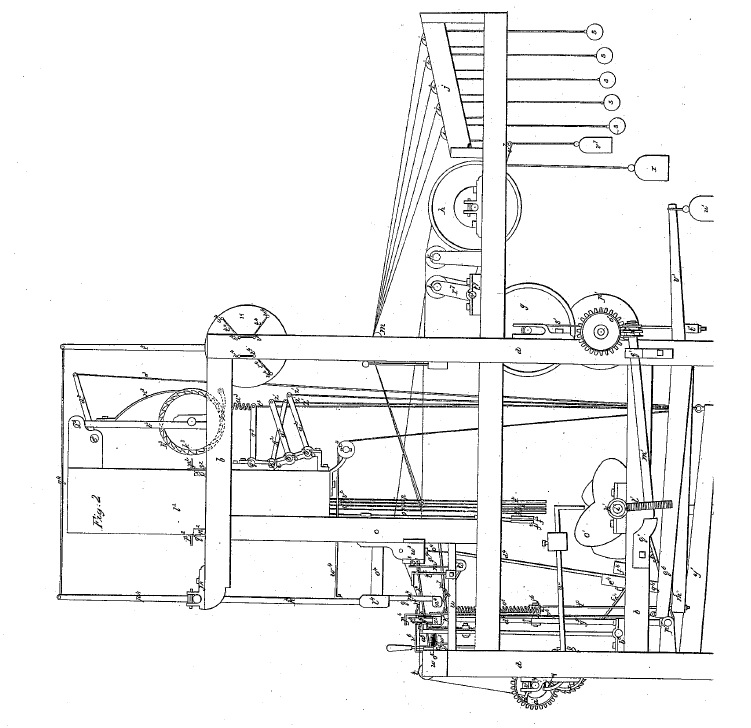

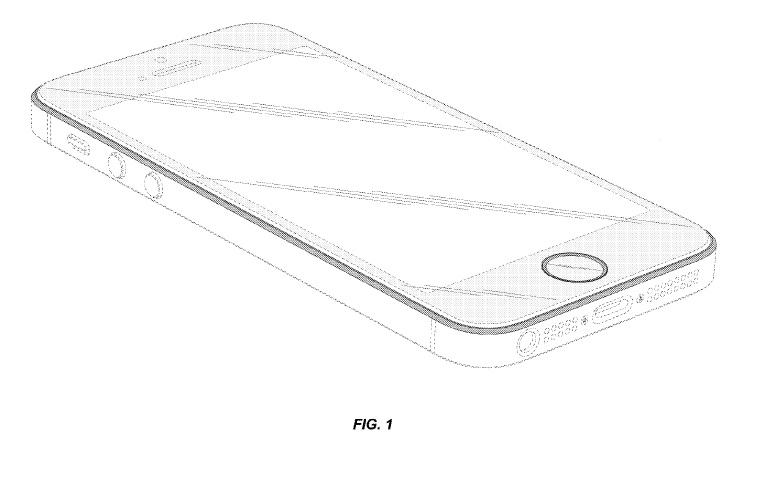

Often the appearance of an article is attributable to the nature of the surface as much as its shape. Reflective surfaces are often depicted in design patent drawings as parallel lines, as in U.S.Patent No. D754125:

The test completes the disclosure: “The oblique shade lines in the Figures show a transparent, reflective, or shiny surface, and not surface ornamentation” (emphasis added). Sometimes the surface is not reflective as much as the material is reflective. This is commonly handled withing shading, and again an explanation in the text, as in U.S. Patent No. D733,397:

The test completes the disclosure: “The oblique shade lines in the Figures show a transparent, reflective, or shiny surface, and not surface ornamentation” (emphasis added). Sometimes the surface is not reflective as much as the material is reflective. This is commonly handled withing shading, and again an explanation in the text, as in U.S. Patent No. D733,397: :”United States Patent: D733397 The stipple shading represents claimed reflective piping” (emphasis added).

:”United States Patent: D733397 The stipple shading represents claimed reflective piping” (emphasis added).

April 29 Patent of the Day

An Illuminating Discussion About Design Patents

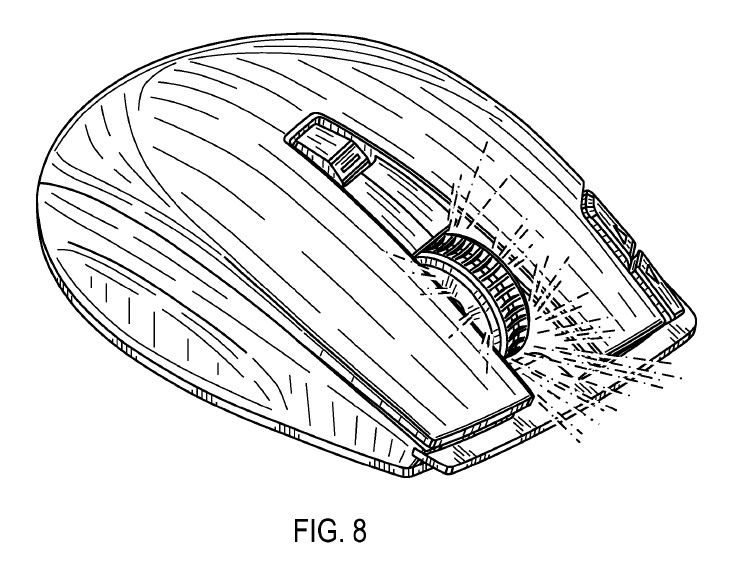

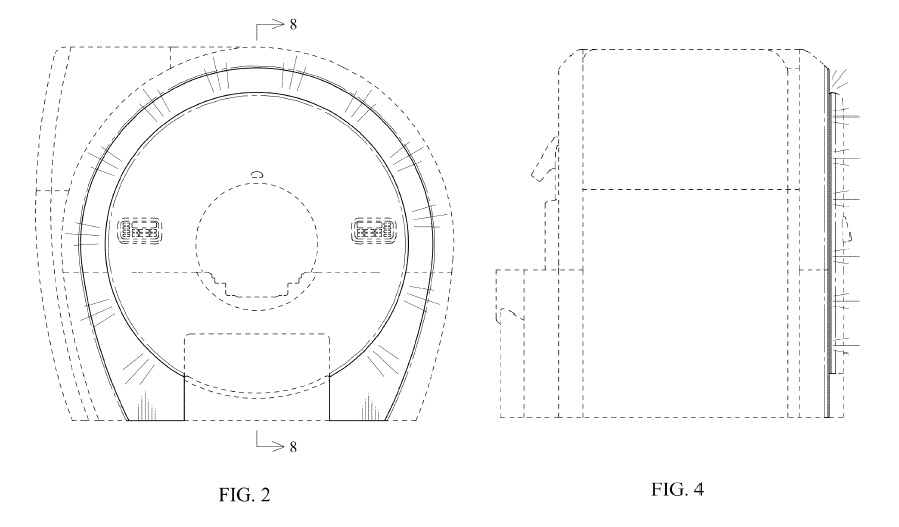

Design patents protect the aesthetic appearance of a product or portion of the product. The aesthetic appearance is affected by a number of things, including whether the product is illuminated. However, how does one capture in the USPTO’s preferred black and white line drawings that fact that some or all of the design is illuminated? Pretty much the way you would think. Take, for example, U.S. Patent No. D688245 on a Contoured Mouse, which illustrates illumination with a burst of radiating dashed lines:

the patent explains that the “dash-dot-dash lines shown in Fig 8 represent the illumination at the finger wheel and these lines form no part of the claimed design.” This same technique was used in U.S. Patent No. D688,664, also on a contoured mouse.

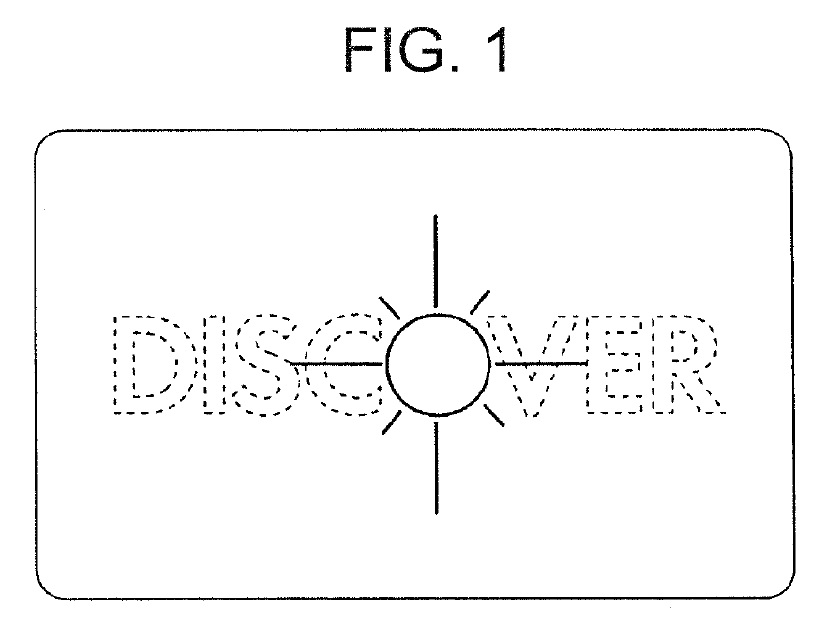

Discover Financial Service used a similar technique to illustrate an illuminated portion on their Discover Card in U.S. Patent No. D685419:

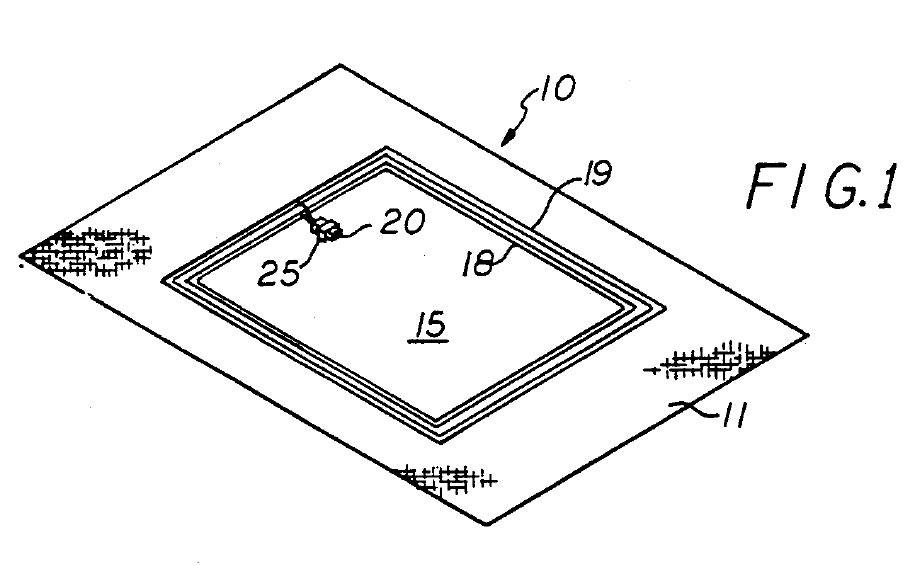

The patent explaining that “The circle is the boundary of the illuminated portion. The radiating lines illustrate the glow of the illumination.” Radiating lines were also used to indicate illumination on an MR scanner in U.S. Patent No. D682,026:

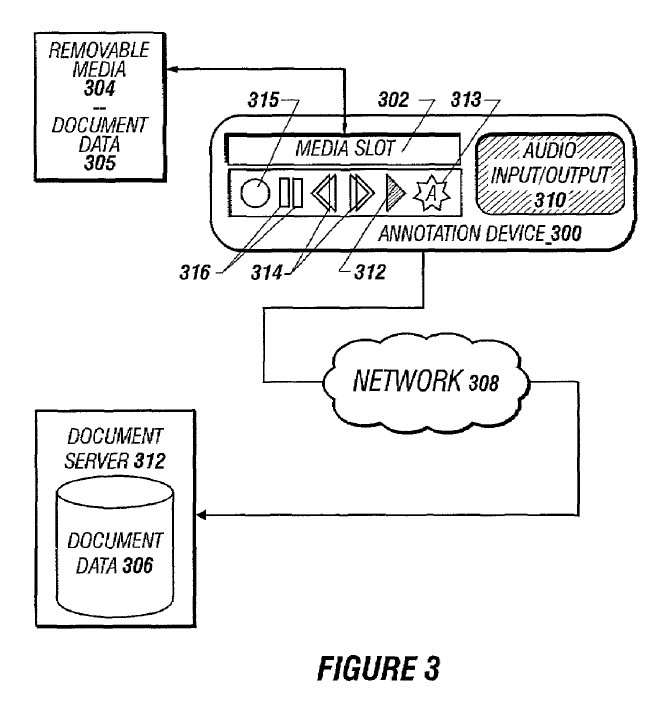

Still other examples include: an electronic data module with illuminated region in U.S. Patent No. D670696:

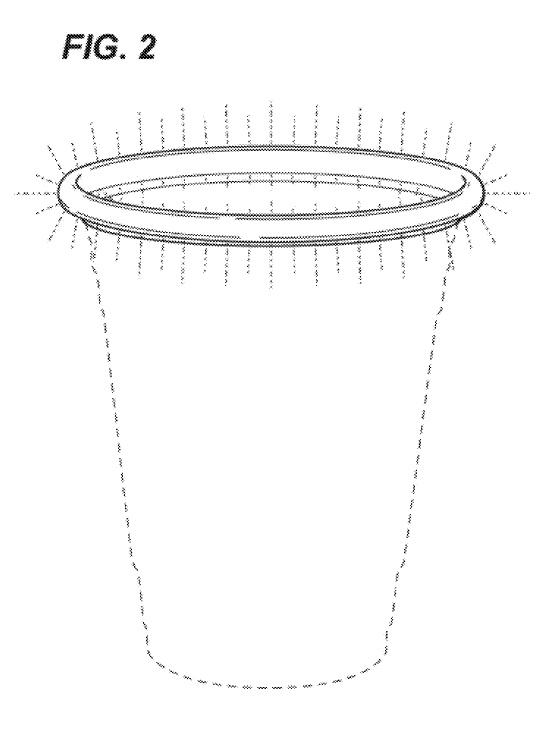

An illuminated cup rim in U.S. Patent No. D670419:

Illumination can be claimed in a design patent, it is simply a matter of illustrating the illumination in the drawings, and describing the drawings properly.

April 28 Patent of the Day

Principles of Equity: Denying Inventors their Constitutionally Promised Exclusivity

Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution, empowers the United States Congress:

To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

However, the patent laws enacted by Congress don’t always provide what the Constitution intended. In Texas Advanced Optoelectrionic Solutions, Inc, v. Intersil Corp., [4:08-CV-451] the district court recently denied the plaintiff patent owner’s motion for a permanent injunction,finding a lack of irreparable harm. The Court relied upon the fact that the patent owner “viewed a reasonable royalty as sufficient compensation for the Defendant’s past infringement,” The Court then ordered the parties:

to negotiate a royalty rate to address any future harm to the Plaintiff for the remaining life of the ‘981 patent. Such supplemental damages shall be for sales in the Unite States of products found to infringe the Plaintiff’s patent from March 2014 until the expiration of the patent. The parties shall have 30 days from the entry of this order to negotiate a royalty rate. If the parties require additional time, they may so move the court. If the parties are unable to successfully negotiate a royalty rate, the Plaintiff may move the court to impose an ongoing royalty rate.

The case arose when, after entering a confidentiality agreement to explore a possible business relationship, Intersil misappropriated TAOS’ trade secrets, and wilffully infringed TAOS’ patent. Despite Intersil’s bad conduct, and the fact the parties were actually competing in the marketplace, the Constitution’s promise of exclusivity is denied on principles of equity.

April 20 Patent of the Day

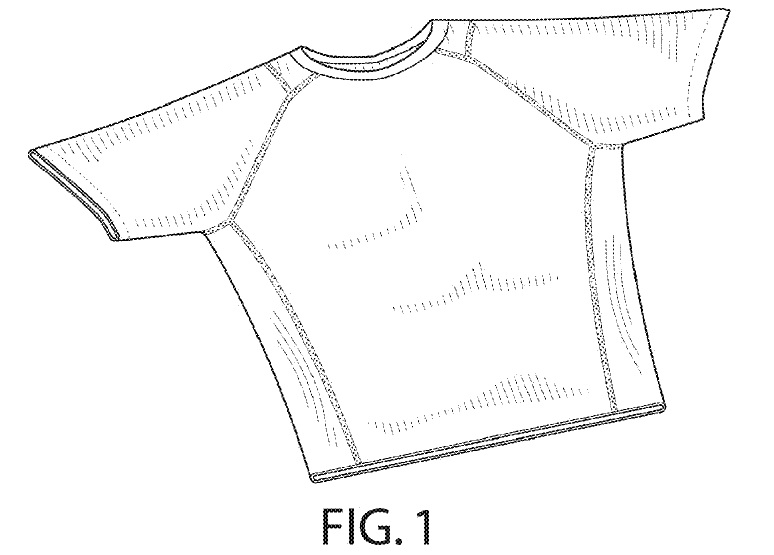

It is Error to Ignore Functional Structures Entirely in a Design Patent Construction

In Sport Dimension, Inc. v. The Coleman Company, [2015-1553] (April 19. 2016) the Federal Circuit vacated the stipulated judgment of non-infringement of U.S. Patent No. D623,714 on a personal flotation device, and remanded for further proceedings consistent with the correct claim construction.

The district court adopted Sport Dimension’s proposed claim construction:

The ornamental design for a personal flotation device, as shown and described in Figures 1–8, except the left and right armband, and the side torso tapering, which are functional and not ornamental.

This construction eliminates several features of Coleman’s claimed design, specifically the armbands and the side torso tapering. The Federal Circuit observed that “[w]ords cannot easily describe ornamental designs.” The Federal Circuit said that a design patent’s claim is thus often better represented by illustrations than a written claim construction, and that a detailed verbal claim constructions increases “the risk of placing undue emphasis on particular features of the design and the risk that a finder of fact will focus on each individual described feature in the verbal description rather than on the design as a whole.

However the Federal Circuit has often “blessed “claim constructions that helped the fact finder distinguish between those features of the claimed design that are ornamental and those that are purely functional, because where a design contains both functional and nonfunctional elements, the scope of the claim must be construed in order to identify the non-functional aspects of the design as shown in the patent.

In OddzOn, Richardson, and Ethicon, the Federal Circuit construed design patent claims so as to assist a finder of fact in distinguishing between functional and ornamental features, but in no case did it entirely eliminate a structural element from the claimed ornamental design, even though that element also served a functional purpose. Even though the Federal Circuit agreed that certain elements of the design serve a useful purpose, it rejected the district court’s ultimate claim construction because it eliminated the functions structures from the claim entirely.

The Federal Circuit said that because of the design’s many functional elements and its minimal ornamentation, the overall claim scope of the claim is accordingly narrow. However the Federal Circuit offered no further guidance on the proper construction.

Equitable Estoppel Stops NPE From Asserting Patents that its Assignor Failed to Assert

In High Point SARL v. Sprint Nextel Corporation, [2015-1298] (April 5, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment that equitable estoppel and laches preclude prosecution of High Point’s claims for infringement of United States Patent Nos. 5,195,090, 5,195,091, 5,305,308, and 5,184,347. High Point is an NPE that acquired the patents from successors of AT&T and Lucent.

The Federal Circuit held that the district court did not abuse its discretion

in determining that equitable estoppel precludes High Point from bringing this case against Defendants. The Court said that three elements must be established for equitable estoppel to bar a patentee’s suit:

- the patentee, through misleading conduct (or

silence), leads the alleged infringer to reasonably

infer that the patentee does not intend to enforce

its patent against the alleged infringer; - the alleged infringer relies on that conduct; and

- the alleged infringer will be materially prejudiced if

the patentee is allowed to proceed with its claim.

The Federal Circuit concluded that High Point’s predecessors’ misleading course of conduct caused Sprint to reasonably infer that they would not assert the patents-in-suit while Sprint purchased unlicensed infrastructure to build its network. The Court said that misleading conduct occurs when the alleged infringer is aware of the patentee or its patents, and knows or can reasonably infer that the patentee has own of the allegedly infringing activities for some time. The Federal Circuit said that the evidence showed both silence and active conduct.

The Federal Circuit also agreed with the district court that Sprint detrimentally relied upon the inaction of High Point’s predecessors.

Finally, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that Sprint were prejudiced by the delay, both economically because of continued investment in the accused technology, and through loss of evidence over time.

The effect of equitable estoppel is “a license to use the invention that extends throughout the life of the patent.”