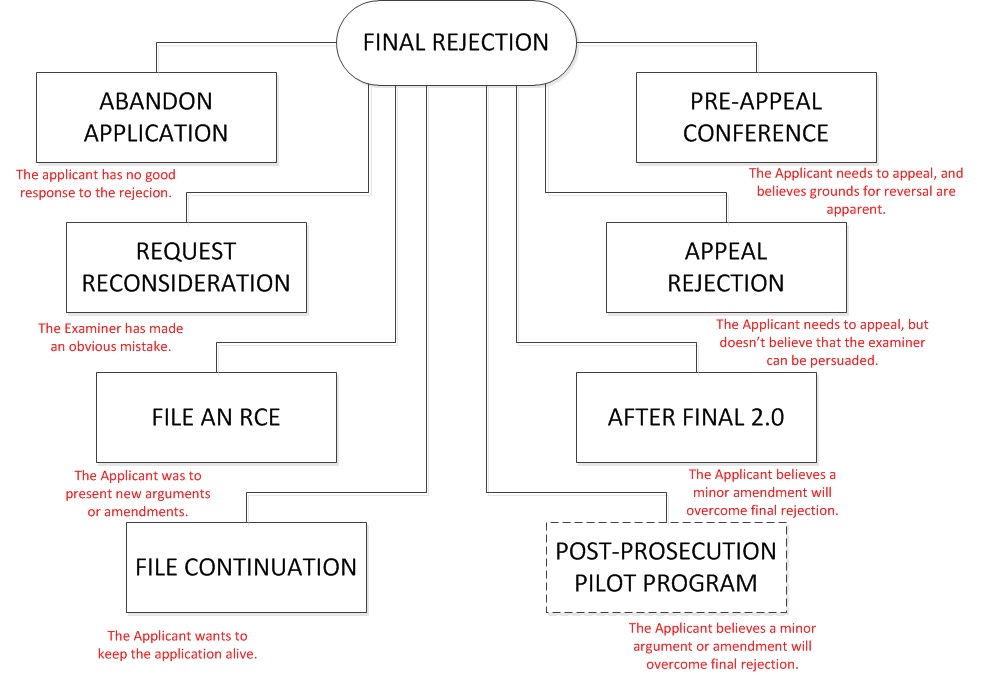

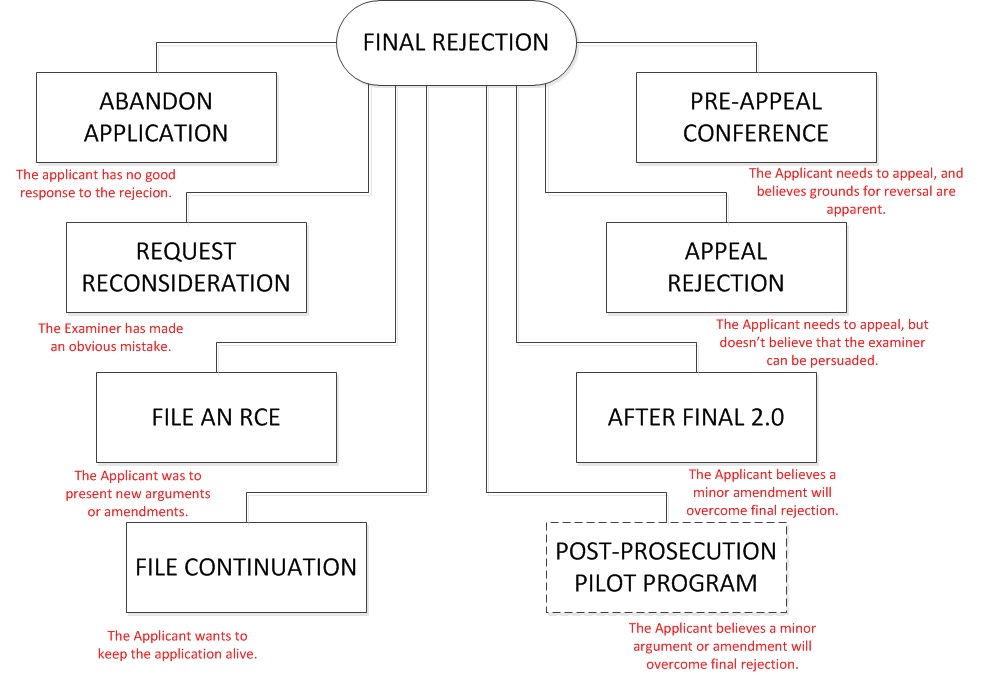

It seems that the majority of patent applications, including those that eventually issue as patents, face a “final” rejection at some point. However, “final” does not not always mean final, and there are at least eight possible responses to a final rejection.

ABANDON APPLICATION

As much as patent prosecutors hate to admit it, every once in a while the Patent Examiner is right, and the only reasonable response to the Final Office Action is to abandon the application.

REQUEST RECONSIDERATION/AMENDMENT AFTER FINAL

Sometimes a Final Office Action will be premised on an a clear mistake of law or fact, which if pointed out the the Examiner, will result in the withdrawal of the finality of the action, and perhaps even an allowance. 37 CFR §§1.113 and 1.116 address responses after a Final Office Action. 37 CFR §1.116 limits amendment to three situations:

- An amendment may be made canceling claims or complying with any requirement of form expressly set forth in a previous Office action

- An amendment presenting rejected claims in better form for consideration on appeal may be admitted; or

- An amendment touching the merits of the application or patent under reexamination may be admitted upon a showing of good and sufficient reasons why the amendment is necessary and was not earlier presented.

Generally, an Examiner will not permit an amendment unless it complies with 37 CFR §1.116. Examiners have no incentive to give any substantial attention to a response after final, and they are rarely effective unless they fully comply with the requirements set forth in the Final Rejection.

FILE A REQUEST FOR CONTINUED EXAMINATION (RCE)

If an applicant wants to continue to prosecute the application, presenting additional arguments and evidence, or amending the claims, then the applicant can request continued examination under 37 CFR §1.114. If an applicant timely files a submission and fee set forth in §1.17(e), the Office will withdraw the finality of any Office Action and the submission will be entered and considered.

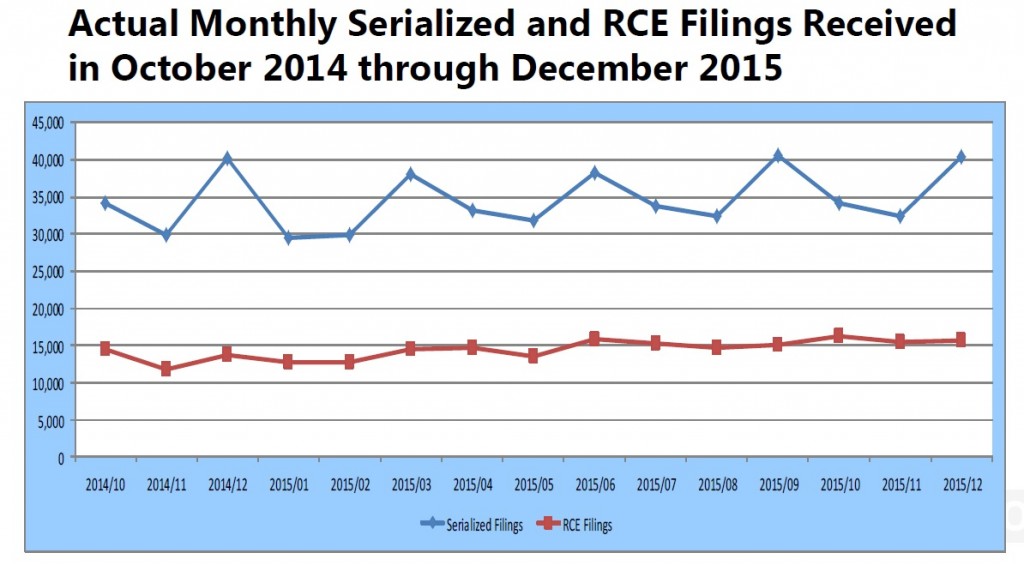

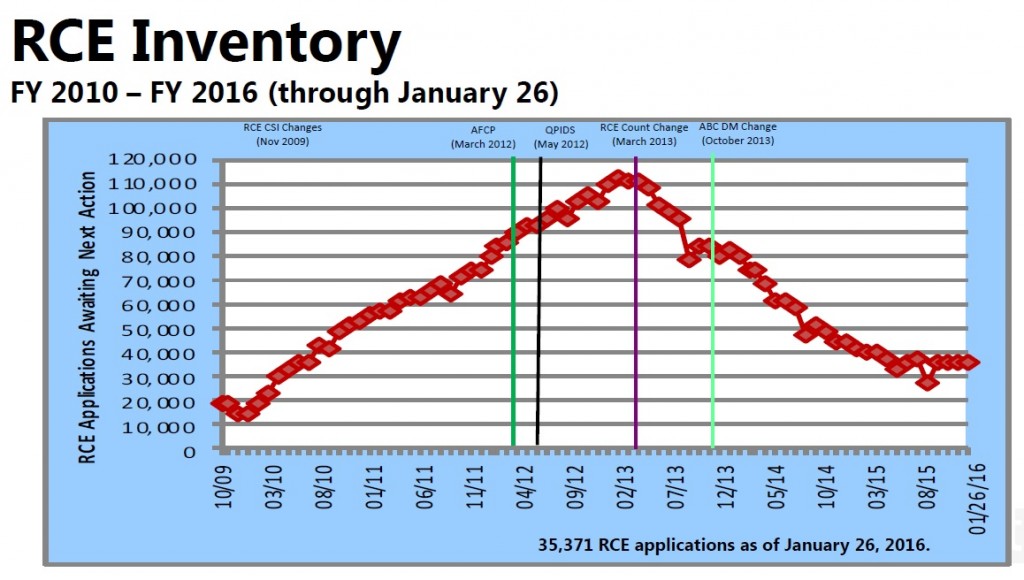

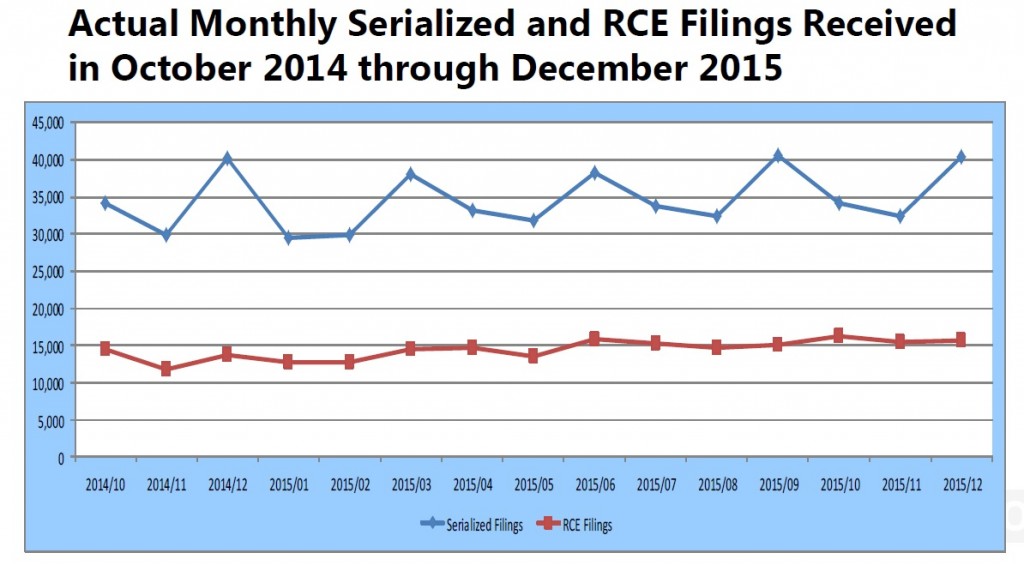

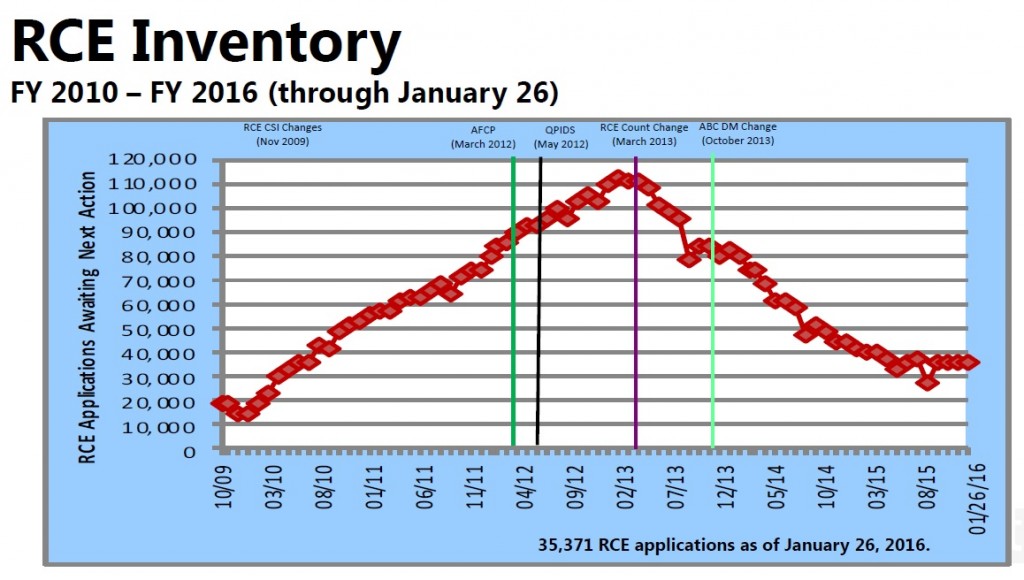

RCE’s are a significant part of patent prosecution. USPTO Statistics show taht approximately 30% of the applications waiting examination are applications in which an RCE has been filed:

The USPTO treatment of RCE’s has changed over time — in 2009 the USPTO changed the Examiner’s incentives to handle RCE, which resulted in a large backlog, but various changes in USPTO policies have resulted in a steady decline in pendency.

FILE A CONTINUATION APPLICATION

An application is always free to restart the application process by filing a continuation application. Unlike an RCE which keeps its original serial number and filing date, a continuation application is a new application, which is assigned a new serial number and filing date (although it claims priority to the parent application). Continuation applications are put at the bottom of the examination pile, and are a good choice for an applicant who wants to keep the application alive, but is not in a position to provide a complete response to the final rejection, which would be required to file an RCE.

AFTER FINAL 2.0

Although a response after final generally won’t be considered, several years ago the USPTO created an After Final Consideration Pilot 2.0 that gives Examiner a limited additional amount of time (and thus an incentive) to consider compliant submissions under the pilot program. The current version of the program, which expires September 30, 2016, requires that the applicant file:

- A request for consideration under AFCP 2.0 (Form PTO/SB/434); and

- A response under 37 CFR 1.116, including an amendment to at least one independent claim that does not broaden the scope of the independent claim in any aspect.

In response to the AFCP submission, the applicant will receive an AFCP 2.0 response form (PTO-2323) that communicates the status of the submission. If the applicant requested an interview, the the form will also be accompanied by an interview summary.

One can request an examiner interview after final in the ordinary course, but it is up to the discretion of the examiner as to whether to grant that interview request. Here, under the AFCP 2.0 program, the examiner is given additional time to search and/or consider the response, but also it gives applicants an additional opportunity to discuss the application with the examiner, if the response does not place the application in a condition for allowance. To date, the USPTO has not published statistics on the AFCP 2.0 program.

POST-PROSECUTION PILOT PROGRAM (P3)

A new alternative for patent applications beginning July 11, 2016, and extending to January 12, 2017, is the Post-Prosecution Pilot Program or P3 Program. The P3 Program provides for (i) an after final response to be considered by a panel of examiners (like the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference), (ii) an after final response to include an optional proposed amendment (like the AFCP 2.0), and (iii) an opportunity for the applicant to make an oral presentation to the panel of examiners (new).

The request for the P3 Program should include:

- A transmittal form, such as form PTO/SB/ 444, that identifies the submission as a P3 submission and requests consideration under the P3 Program

- A response under 37 CFR 1.116 comprising no more than five pages of argument; and

- A statement that the applicant is willing and available to participate in the conference with the panel of examiners.

- (Optionally) A proposed non-broadening amendment to a claim(s).

There is no fee required to request consideration under the P3 Program. All papers

associated with a P3 Program request must be filed via the USPTO’s Electronic Filing

System-Web (EFS-Web), and the applicant must not have previously filed a proper request to participate in the Pre-Appeal program or a proper request under AFCP 2.0 in response to the same outstanding final rejection. The program ends when a total of 1,600 P3 Program requests have been accpted (200 per art unit), or January 12, 2017 whichever occurs first.

PRE-APPEAL BRIEF CONFERENCE

For applicants who have made all the amendments they are willing to make, and presented all of the arguments it has, the is one last stop before an full-blown appeal to the Patent Trials and Appeals Board: the pre-appeal brief conference.

The request must be filed with the Notice of Appeal, and can include up to five pages of reasons why the final rejection is incorrect. The point of the pre-appeal conference is that the Examiner must discuss (hence “conference) the final rejection with at least two other Examiners. The hope of applicants, of course, is that the two other Examiner’s will provide a voice of reason so that the final rejection will be withdrawn and the case allowed. However that is only one of the possible outcomes.

In 2015, IP Watchdog posted the results of a FOIA request for data on the effectiveness of the Pre-Appeal Brief Conferences, the data showed that of the non-defective requests, only 6% resulted in an allowance. 61% of the time, the conference panel decided that there was an issue for appeal. 33% of the time, the conference resulted in a reopening of prosecution, which is at least a partial victory for the applicant.

Drilling down a little further, of the 61% of applications where the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference found an appealable issue, 58% of these applications eventually issued as patents. Of the 33% of applications where the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference reopened prosecution, nearly 80% of these applications eventually issued as patents. This data represented the ten years’ experience between when the program began in 2005 through 2015, although the trend since 2009 has been an ever-increasing percentage of Pre-Appeal Brief Conferences finding an appealable issue.

APPEAL

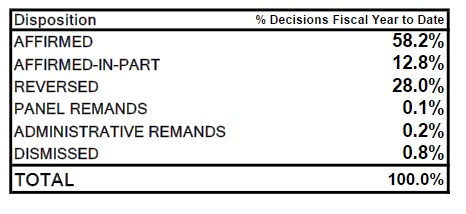

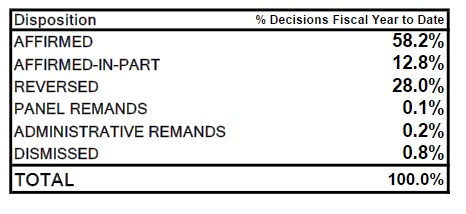

After all the amendments have been made and arguments presented, an applicant is left with no choice but to appeal, The cost of an appeal is not insignificant, with a Notice of Appeal Fee, the cost of preparing the Brief on Appeal, and the Appeal consideration fee, an applicant can easily spent $8,000 to $12,000, before oral argument. The time involved is also considerable — typically three to four years. The current (2016) success rate is about 40%, with Examiner being affirmed about 58.2% of the time, being reversed about 28.0% of the time, and partially reversed another 12.8% of the time.

i