On February 18, 1879, U.S. Patent No. D11,023 issued to Auguste Bartholdi on a Statute (the Statute of Liberty):

February 17 Patent of the Day

February 16 Patent of the Day

February 15 Patent of the Day

February 14 Patent of the Day

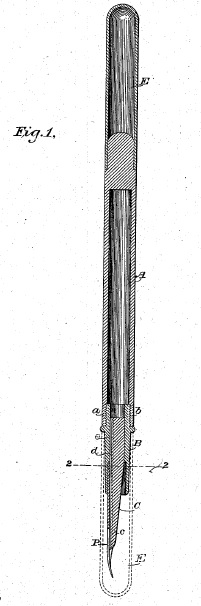

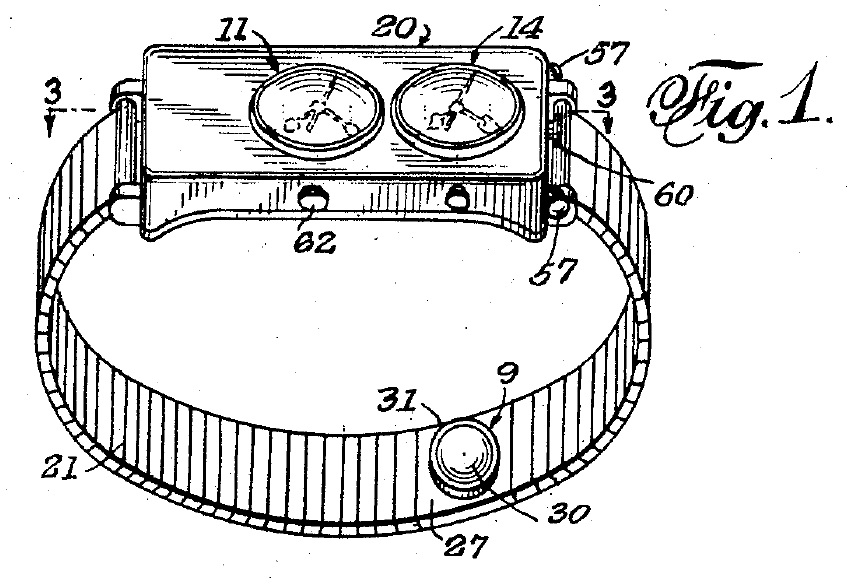

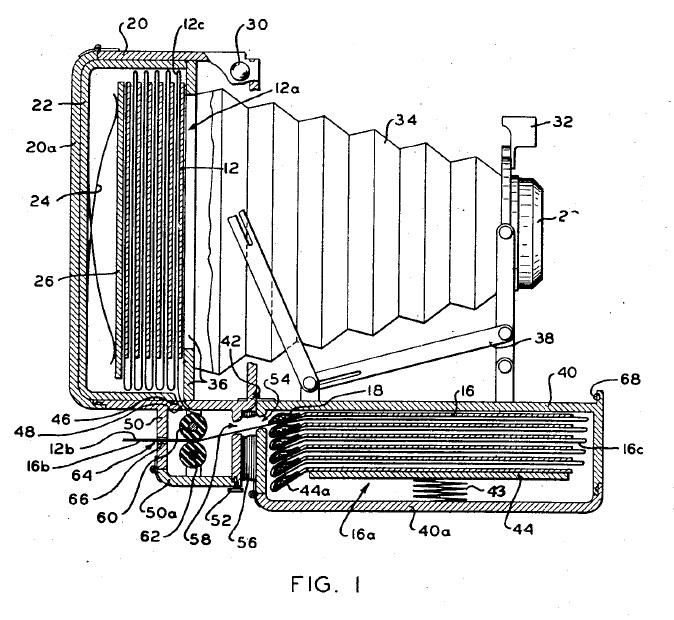

On February 14, 1871, U.S. Patent No. 111,798 issued to Thomas Adams on an Improvement in Chewing-Gum.

Adams conceived the idea while working as a secretary to former Mexican leader Santa Anna, who chewed a natural gum called chicle. After failing to turn it to a rubber suitable for tires, he made the chicle into a chewing gum called Chiclets.

February 13 Patent of the Day

February 12 Patent of the Day

February 11 Patent of the Day

February 10 Patent of the Day

Actual Knowledge of a Published Application Can Trigger Pre-Issuance Damage (Quick Put Your Head in the Sand)

In Rosebud LMS Inc. v. Adobe systems Inc., [2015-1428] (February 9, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed the grant of summary judgment that Adobe Systems Inc. was not liable for pre-issuance damages under 35 U.S.C. §154(d) because it had no actual notice of the published patent application that led to asserted U.S. Patent No. 8,578,280.

35 USC 154(d) provides that:

a patent shall include the right to obtain a reasonable royalty from any person who, during the period beginning on the date of publication of the application for such patent under section 122(b) . . .and ending on the date the patent is issued (A)(i) makes, uses, offers for sale, or sells in the United States the invention as claimed in the published patent application or imports such an invention into the United States; . . . and (B) had actual notice of the published patent application

The Rosebud argued that Adobe had actual notice of its patents because it had previously sued Adobe on the grandparent of the patent in suit, that Adobe followed Rosebud and its product and sought to emulate some of its product’s features; and that it would have been standard practice in the industry for Adobe’s counsel to search for related patents. Adobe, without conceding knowledge, argued that some affirmative action on the part of Rosebud was required to put Adobe on “actual notice” of the patent.

In a case of first impression, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument that some action on the part of patent owner is required for actual notice, but agreed that constructive notice is not sufficient to give “actual notice.” Adobe presented a compelling argument based upon the legislative history of 154(d), but the Fedearl Circuit noted that the language enacted by Congress was not consistent with Adobe’s interpretation. The Federal Circuit also distinguished the interpretation of 287(a) requiring an affirmative act to put an infringer on notice to be entitled to damages, noting the difference in the language of the two sections and noting that Congress could have used similar language in 154(d), but did not.

Noting several good reasons why some affirmative action on the part of the patent owner might make good policy sense, the Federal Circuit invited Congress to amend the statute if it wants a different result.

Even under this lesser standard for actual notice, the Federal Circuit agreed that Rosebud failed to show that Adobe had actual notice of the patent. The Federal Circuit did not find that the earlier litigation on the grandparent of the current patent necessarily put Adobe on notice of the published application, it rejected the argument Adobe “followed” Rosebud and its products, is insufficient, and lastly rejected the argument that Adobe’s outside counsel would have discovered the publication preparing for the earlier litigation, noting that it never reached the claim construction stage because Rosebud missed all of its court-ordered deadlines.

Companies should rethink their competition monitoring programs. Acquiring actual knowledge of a published application increases the company’s exposure to pre-issuance damages. If the company actually uses its knowledge of the published application to reduce its liability — for example by designing around the claims or finding invalidating prior art — then this increased exposure is probably worth it. However, if the knowledge of the published application is not going to be put to good use, the increased exposure comes with no benefit.

,