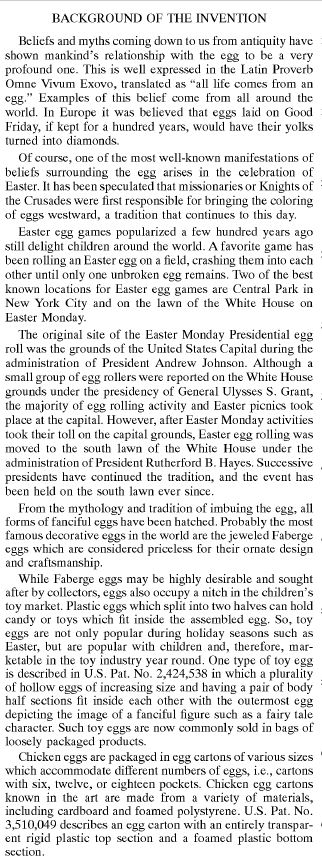

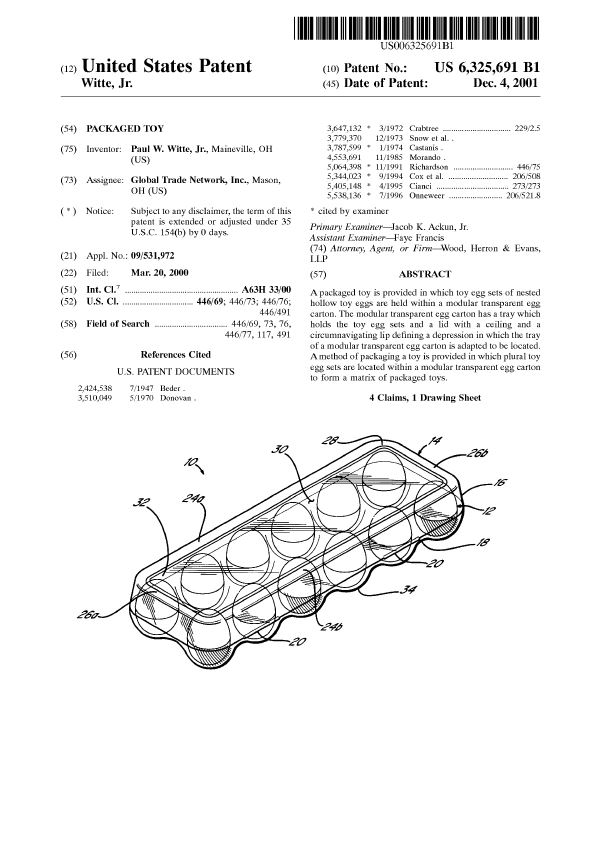

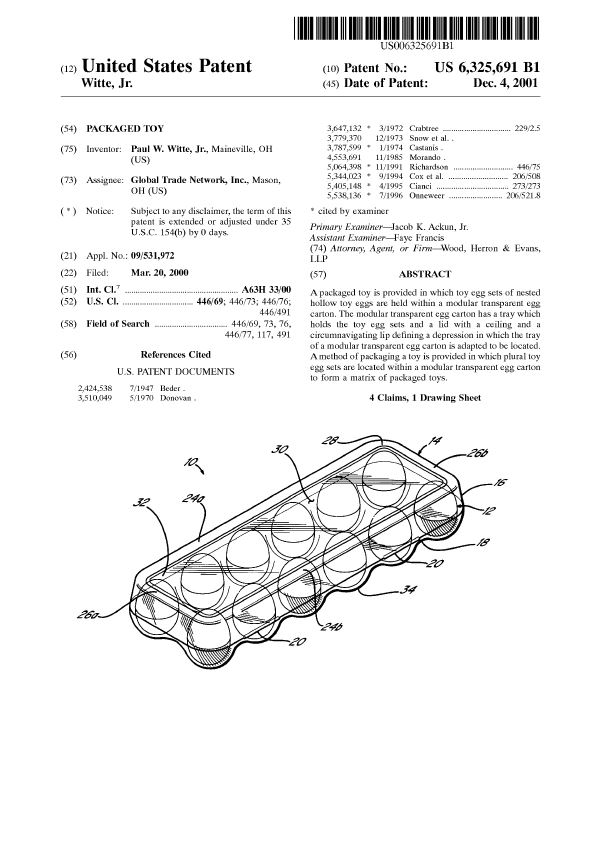

There is all sorts of valuable information in the U.S. Patent collection, and from U.S. Patent No. 6,325,691, we learn all about the Easter Egg tradition, including the incredible investment potential of Good Friday eggs:

There is all sorts of valuable information in the U.S. Patent collection, and from U.S. Patent No. 6,325,691, we learn all about the Easter Egg tradition, including the incredible investment potential of Good Friday eggs:

In Nevro Corp. v. Boston Scientific Corporation, [2018-2220, 2018-2340] (April 9, 2020) the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the District Court determination on summary judgment that claims 7, 12, 35, 37 and 58 of U.S. Patent No. 8,712,533, claims 18, 34 and 55 of U.S. Patent No. 9,327,125, claims 5 and 34 of U.S. Patent No. 9,333,357, and claims 1 and 22 of U.S. Patent No. 9,480,842 were indefinite. The claimed invention purportedly improves conventional spinal cord stimulation therapy by using waveforms with high frequency elements or components, which are intended to reduce or eliminate side effects.

The district court determined that “paresthesia-free” has a “clear meaning,” namely that the therapy or therapy signal “does not produce a sensation usually described as tingling, pins and needles, or numbness.” The district court therefore held that the term “paresthesia-free” does not render the asserted method claims indefinite. does not render the asserted method claims indefinite. Id. The district court held indefinite, however, the asserted “paresthesia-free” system and device claims. It held that infringement of these claims depended upon the effect of the system on a patient, and not a parameter of the system or device itself and therefore, “a skilled artisan cannot identify the bounds of these claims with reasonable certainty.”

Claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, must “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” This standard “mandates clarity, while recognizing that absolute precision is unattainable.” The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court correctly determined that the “paresthesia-free” method claims are not indefinite, but that it erred in holding indefinite the “paresthesia-free” system and device claims. The test for indefiniteness is not whether infringement of the claim must be determined on a case-by-case basis. Instead, it is simply whether a claim “inform[s] those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.”

The Federal Circuit said that “paresthesia-free” is a functional term, defined by what it does rather than what it is, but that that does not inherently render it indefinite. In fact, the Federal Circuit said that functional language can promote definiteness because it helps bound the scope of the claims by specifying the operations that the claimed invention must undertake. When a claim limitation is defined in purely functional terms, a determination of whether the limitation is sufficiently definite is highly dependent on context (e.g., the disclosure in the specification and the knowledge of a person of ordinary skill in the relevant art area). The ambiguity inherent in functional terms may be resolved where the patent provides a general guideline and examples sufficient to enable a person of ordinary skill in the art to determine the scope of the claims.

The Federal Circuit found that the specification teaches how to generate and deliver the claimed signals using the recited parameters. Accordingly, a person of ordinary skill would know whether a spinal cord stimulation system, device or method is within the claim scope. Thus, the patents provide reasonable certainty about the claimed inventions’ scope by giving detailed guidance and examples of systems and devices that generate and deliver paresthesia-free signals with high frequency, low amplitude, and other parameters.

The Federal Circuit rejected Boston Scientific’s argument that the “paresthesia-free” claims are indefinite because infringement can only be determined after using the device or performing the method. The Federal Circuit said that “Definiteness does not require that a potential infringer be able to determine ex ante if a particular act infringes the claims.”

Several of the claims recited a signal generator “configured to” generate a therapy signal with certain parameters and functions. The district court concluded that “configured to” could be “reasonably construed to mean one of two things: (1) the signal generator, as a matter of hardware and firmware, has the capacity to generate the described electrical signals (either without further programing or after further programming by the clinical programming software); or (2) the signal generator has been programmed by the clinical programmer to generate the described electrical signals. Because the term was susceptible to two different constructions, the district court concluded that “configured to” made the claims indefinite.

The Federal Circuit said that this was the incorrect legal standard. The test for indefiniteness is whether the claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty. The Federal Circuit said that the test is not merely whether a claim is susceptible to differing interpretations, as such a test would render nearly every claim term indefinite so long as a party could manufacture a plausible construction. The Federal Circuit held that “configured to” does not render the claims indefinite.

Several of the claims included the limitation “means for generating” a paresthesia-free or non-paresthesia-producing therapy signal. The district court determined that there was not an adequate disclosure of a corresponding structure in the patent specification and sua sponte held the claims indefinite.

The Federal Circuit noted that the specification clearly recites a signal or pulse generator, not a general-purpose computer or processor, as the structure for the claimed “generating” function. The Federal Circuit furtner noted that the specification teaches further how to configure the signal generators to generate and deliver the claimed signals using the recited parameters, clearly linking the structure to the recited function. The Federal Circuit reversed the finding of indefiniteness.

Finally, all but four of the claims used the term “therapy signal,” which the district court construed as an “electrical impulse” or “electrical signal,” but which the patent owner argued meant “a spinal cord stimulation or modulation signal to treat pain.”

The Federal Circuit disagreed that the specification met the exacting standard of define “therapy signal” as the Federal Circuit found. The Federal Circuit also rejected the argument that the language was indefinite, holding that the fact that a signal does not provide pain relief in all circumstances does not render the claims indefinite. The Federal Circuit held that the district court incorrectly construed the claim, but correctly determined that the claim was not indefinite.

In Nike, Inc.v. Adidas AG, [2019-1262] (April 9, 2020) The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s the Board’s finding that Nike failed to establish a long-felt need for substitute claims 47–50, but vacated the Board’s decision of obviousness as to substitute claim 49 because no notice was provided to Nike for the Board’s theory of unpatentability.

The case involved U.S. Patent No. 7,347,011, which discloses articles of footwear having a textile “upper,” which is made from a knitted textile using any number of warp knitting or weft knitting processes. The case in an appeal after remand from a previously appeal where the Federal Circuit affirmed-in-part and vacated-in-part the Board’s decision denying Nike’s motion to amend. Nike is again appealing the denial of its motion motion to enter substitute claims 47–50.

Substitute claim 49 recites a knit textile upper containing “apertures” that can be used to receive laces and that are “formed by omitting stitches” in the knit textile. Adidas opposed substitute claim 49, arguing that it was obvious form the combination of three prior art references: U.S. Patent No. 5,345,638 (Nishida); U.S. Patent No. 2,178,941 (Schuessler I); and U.S. Patent No. 2,150,730 (Schuessler II), and in particular that Nishida disclosed substitute claim 49’s limitation that the apertures are “formed by omitting stitches.” The Board found that Nishida does not disclose apertures formed by omitting stitches, as recited in claim 49, but that another prior art document of record in the proceeding demonstrates that skipping stitches to form apertures was a well-known technique.

Nike, having no chance to address this finding, appealed. The Federal Circuit held that the Board may sua sponte identify a patentability issue for a proposed substitute claim based on the prior art of record. However, if the Board sua sponte identifies a patentability issue for a proposed substitute claim, however, it must provide notice of the issue and an opportunity for the parties to respond before issuing a final decision under 35 U.S.C. § 318(a).

Because the case involves a motion to amend, The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board should not be constrained to arguments and theories raised by the petitioner in its petition or opposition to the motion to amend. However the Federal Circuit reserved for another day the question of the Board may look outside of the IPR record in determining the patentability of proposed substitute claims.

Although the Board was permitted to raise a patentability theory based on Spencer, the notice provisions of the APA and Federal Circuit case law require that the Board provide notice of its intent to rely on Spencer and an opportunity for the parties to respond before issuing a final decision relying on Spencer. Under the APA, “[p]ersons entitled to notice of an agency hearing shall be timely informed of of fact and law asserted,” 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3), and the agency “shall give all interested parties opportunity for . . . the submission and consideration of facts [and] arguments,” id. § 554(c)(1).

In Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. v. Mylan Phamaceuticals Inc., [2018-2097] (April 8, 2020) the Federal Circuit reversed and remanded that district court’s grant of summary judgment that claim 8 of U.S. 8,552,025 is not invalid.

The ‘025 claims stable methylnaltrexone pharmaceutical preparations. Claim 8 recites “[t]he pharmaceutical preparation of claim 1, wherein the preparation is stable to storage for 24 months at about room temperature.”

Mylan argued that the district court erred in at least two respects: (1) by failing to hold that Mylan established a prima facie case that claim 8 would have been obvious because the pH range in the claim overlaps with pH ranges in the prior art for similar compounds and (2) by resolving disputed fact issues at summary judgment.

The Federal Circuit agreed with Mylan that the record supports a prima facie case of obviousness. Here, the pH range recited in claim 8 clearly overlaps with the pH range in the record art, but none of the references disclose the same drug as the one claimed. The qestion was whether prior art ranges for solutions of structurally and functionally similar compounds that overlap with a claimed range can establish a prima facie case of obviousness. The Federal Circuit conclude that they can and, in this case, do. The Federal Circuit noted that its case law reflects an understanding that skilled artisans can expect structurally similar compounds to have similar properties, and that that an obviousness analysis can rely on prior art compounds with similar pharmacological utility in addition to structural similarity.

Because these three molecules bear significant struc-tural and functionality similarity, and because the prior art of record teaches pH ranges that overlap with the pH range recited in claim 8, Mylan has at least raised a prima facie case of obviousness sufficient to survive summary judgment.

In BASF Corp. v. SNF Holding Co., [2019-1243] (April 8, 2020), the Federal Circuit reversed summary judgment of invalidity of claims U.S. Patent 5,633,329, finding that the asserted prior art did not create an on-sale bar, an public use bar, or prior knowledge or use.

The Federal Circuit held that the asserted prior art Sanwet® Process does not create an on-sale bar to the ’329 patent under § 102(b), and further that the district court misinterpreted § 102(a) and the public-use bar of § 102(b), and that under the proper legal standard, genuine issues of material fact preclude the entry of summary judgment on those issues.

§102(a) Prior Knowledge or Use

BASF first argued that the district court misinterpreted the phrase “known or used” in § 102(a) and erroneously disregarded the confidentiality of Celanese’s knowledge and use. In BASF’s view, knowledge or use that is not publicly accessible does not qualify as prior art under § 102(a). The Federal Circuit agreed, noting that it has This court has uniformly interpreted the “known or used” prong of § 102(a) to mean “knowledge or use which is accessible to the public.” The Federal Circuit concluded that the record reveals genuine issues of material fact as to whether the asserted Sanwet® Process was “known or used” within the meaning of § 102(a), as set forth above.5 We therefore reverse the district court’s summary judgment of invalidity and remand for a determination of SNF’s § 102(a) defense at trial.

§ 102(b) Public Use

BASF also argued that the district court’s summary judgment on public use was in error, conntending that the district court misinterpreted the public-use bar of § 102(b) to apply to a third party’s secret commercial use. The Federal Circuit again agreed with BASF, noting that in Shimadzu, the Supreme Court explained that the public-use bar applies to uses of the invention “not purposely hidden” and held that the use of a process in the ordinary course of business—where the process was “well known to the employees” and no “efforts were made to conceal” it from anyone else—is a public use. The Federal Circuit noted that it has applied Shimadzu in its public-use cases. The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court erred in finding, on summary judgment, that the claimed process was publicly accessible. Neither party disputes that members of the public were given access to the Portsmouth plant on numerous occasions, where they could view the shape of the conical taper, and that no evidence suggests that any of these guests was a skilled artisan. The parties dispute whether the remaining elements of the Sanwet® Process were known, and to the extent they were not, whether they were concealed from the public on these tours, in newspaper articles, and in the commemoration video.

The Federal Circuit rejected as “simply wrong” SNF’s second contention—that a third party’s commercial exploitation of a secret process creates a per se public-use bar to another inventor.

§102(b) On Sale

BASF argued that the agreement between Sanyo and Celanese to license the Sanwet® Process was not a sale under In re Kollar. The Federal Circuit agreed that the district court’s judgment must be reversed. Neither the Sanyo-Celanese license agreement nor the 1987 Hoechst acquisition of Celanese is a sale of the invention within the meaning of § 102(b). The Federal Circuit said the invention itself must be sold or offered for sale, and the mere existence of a “commercial benefit . . . is not enough to trigger the on-sale bar” on its own. To determine whether such a commercial sale or offer for sale has occurred, we look to how those terms are defined in the Uni-form Commercial Code. The Federal Circuit recognized that a process, however, is a different kind of invention; it consists of acts, rather than a tangible item, as is contemplated by the U.C.C.’s definition of sale. Yet, in cer-tain circumstances, a process may be sold in a manner which triggers the on-sale bar. For example, performing the process itself for consideration is sufficient. So is a patentee’s sale of a product made by his later-patented process.

Because the district court misinterpreted § 102(a) prior knowledge and use, as well as the public-use bar of § 102(b), the Federal Circuit reversed its summary judgment and remand for trial on those defenses.

In Keith Manufacturing Co. v. Butterfield, [2019-1136] (April 7, 2020), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision not to award attorneys fees Butterfield after dismissal of the action brought by Keith.

Keith Manufacturing Co. brought this lawsuit against Larry D. Butterfield in the United States District Court for the District of Oregon. Eighteen months after the litigation began, the parties filed a stipulation to dismiss all claims with prejudice under Rule 41(a)(1)(A)(ii) of the Fed-eral Rules of Civil Procedure. Shortly after, Butterfield filed a motion for attorney’s fees under Rule 54 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The district court reasoned that a voluntary dismissal with prejudice is not a “judgment” as required by Rule 54(d).

Rule 54 requires that a claim for attorney’s fees “must be made by motion unless the substantive law requires those fees to be proved at trial as an element of damages.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(d)(2)(A). Rule 54 motions must: “(i) be filed no later than 14 days after the entry of judgment; and specify the judgment and the statute, rule, or other grounds entitling the movant to the award.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(d)(2)(B)(i)–(ii). “‘Judgment’ as used in these rules includes a decree and any order from which an appeal lies.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(a).

The issue before the district court and on appeal was whether the stipulated dismissal with prejudice constitutes a judgment for the purposes of Rule 54. The Federal Circuit said that although Rule 54(d) “posits a relationship between a judgment and its appealability, this relationship exists for the prudential purpose of minimizing piecemeal appellate litigation, not because a shared technical construction mandates the relationship.

The Federal Circuit reasoned that treating a voluntary stipulation with prejudice as a judgment for purposes of attorney’s fees under Rule 54 will not invite parties to engage in piecemeal appellate litigation. The joint stipulation means that, except under rare circumstances, there will not be an appeal on the merits; only the attorney’s fees issue remains. Second, where the case is not a class action, it will not undermine class action procedure. And because both parties can move for attorney’s fees, permitting a Rule 54(d) motion for attorney’s fees after a stipulated dismissal will not affect the overall balance of litigation.

The Federal Circuit vacated the district court’s denial of attorneys fees, and remanded for further proceedings.

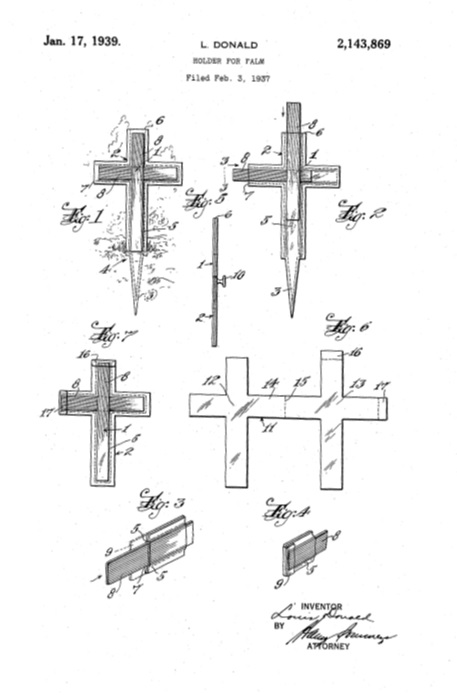

It’s Palm Sunday, and U.S. Patent No. 2,143,869 provides a holder for your palms:

In Intellisoft. Ltd. v. Acer America Corp., [2019-1522] (April 3, 2020), the Federal Circuit reverses the district court’s decision refusing to remand the case to state court, vacate the district court’s judgment, and remanded to the district court with instructions to remand the action to California state court.

Intellisoft Ltd. allegedly shared with Acer trade secrets concerning computer power management technology under a non-disclosure agreement (“NDA”). The NDA allowed Acer to use of their “Confidential Information” only to “directly further” the evaluation of Intellisoft’s product for licensing. Intellisoft alleges that they discovered that Acer had applied for a patent that incorporated their trade secrets and became the owner of U.S. Patent No. 5,410,713 (and related patents 5,870,613; 5,884,087; and 5,903,765). Intellisoft sued Acer in California state court. concluded that Acer had misappropriated their trade secrets and violated the NDA.

Acer cross-claimed that Intellisoft’s inventor, Bierman was not an inventor of the the ‘713 patent family, and removed the case from state court. Intellisoft sought remand to state court because no patent issues had to be resolved to determine its trade secret claim. The district court denied Intellisoft’s motion, and granted summary judgment in favor of Acer with respect to Intellisoft’s state law claims, reasoning that Intellisoft failed to prove under federal patent law that Bierman was the inventor of the ’713 patent family claims.

Under Gunn v. .Minton, when a plaintiff brings only a state law claim, as here, the district court will have original jurisdiction over the state law claim if a federal issue is: (1) necessarily raised, (2) actually disputed, (3) substantial, and (4) capable of resolution in federal court without disrupting the federal-state balance approved by Congress.

The Federal Circuit found that Acer did not establish that Intellisoft’s trade secret claim necessarily raised patent law issues. The Federal Circuit said that ownership of a trade secret under state law did not require proof of patent inventorship. The Federal Circuit further found that Intellisoft did not need to prove infringement to prove trade secret misappropriation. The ’713 patent family was only being used as evidence to support Intellisoft’s state law claims. This analysis required no construction of the claims or proof of infringement. The Federal Circuit further found that Intellisoft’s damages claim was based on using trade secrets, independent of the ‘713 patent family. Mere reliance on a patent as evidence to support its state law claims does not necessarily require resolution of a substantial patent question.

The Federal Circuit found that because Intellisoft’s trade secret claim did not necessarily depend on resolution of a substantial question of federal patent law, so it did not need to address other prongs of the Gunn test. The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court did not have jurisdiction under section 1338(a), and the state law claims could not be removed under section 1441.

The Federal Circuit further found that removal under section 1454 was improper because Acer’s counterclaim was not operative.

In Myco Industries, Inc. v. Blephex. LLC, [2019-2374] (April 3, 2020), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s preliminary injunction enjoining BlephEx from making allegations of patent infringement and also from threatening litigation against Myco’s potential customers over U.S. Patent No. 9,039,718, entitled “Method and Device for Treating an Ocular Disorder,”

The Federal Circuit said that when a preliminary injunction prevents a patentee from communicating its patent rights, a court applies federal patent law and precedent relating to the giving of notice of patent rights. In such cases, the grant of a preliminary injunction is reviewed in the context of whether, under applicable federal law, the notice of patent rights was properly given. The Federal Circuit further said that federal law requires a showing of bad faith before a patentee can be enjoined from communicating his patent rights. A showing of “bad faith” must be supported by a finding that the claims asserted were objectively baseless, and an asserted claim is objectively baseless if no reasonable litigant could realistically expect success on the merits.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court abused its discretion when it granted a preliminary injunction enjoining patentee speech with-out a finding of bad faith. The Federal Circuit said that although a district court’s discretion to enter a preliminary injunction is entitled to substantial deference, the patent laws permit a patentee to inform a potential infringer of the existence of its patent. The Federal Circuit found that the district court neither made a finding of bad faith nor even adverted to the requirement. The Federal Circuit added that to the extent the district court made any factual findings relevant to bad faith, the court expressly declined to find that any of BlephEx’s statements were either false or misleading.

The Federal Circuit rejected Myco’s argument that it would be bad faith to accuse physicians with infringement in view of 35 U.S.C. § 287(c)(1), but the Federal Circuit said the statute did not make physicians “immune from infringement,” it merely prevents the patent owner from seeking a remedy. Further, the District Court found no evidence that any threats were made.

Finally the Federal Circuit vacated the finding that Myco was likely to succeed on the merits, finding several lapses in the district court’s efforts at claim construction.

The Federal Circuit concluded:

Speech is not to be enjoined lightly. Here, there is not even a finding, let alone a finding supported by evidence and a correct view of the law, that the speech restrained was either false or misleading. The district court abused its discretion when it granted a preliminary injunction en-joining BlephEx from making allegations of patent infringement without a finding of bad faith and with no adequate basis to conclude that allegations of patent infringement would be false or misleading.

The Vernal Equinox, and the start of Spring, occurred March 19, 2020, at 10:59 PM CDT.