Another holiday celebrated though the records of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Happy Easter to all who celebrate it (or just like candy).

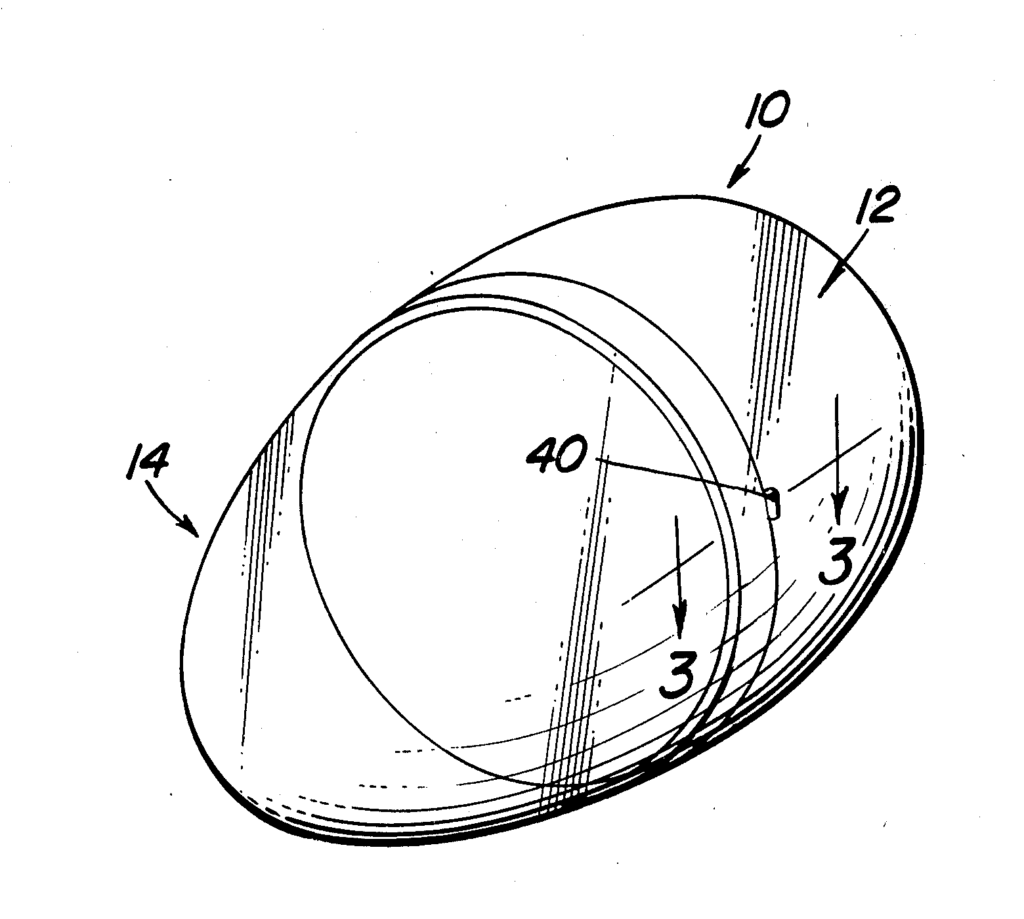

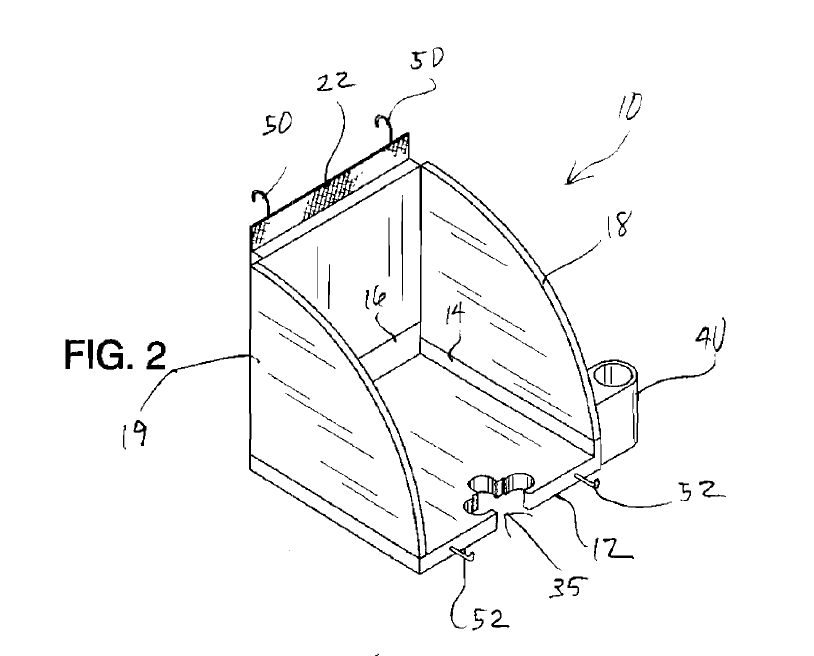

In a St. Patrick’s Day blog, the use of a common shape (in this case the shamrock) as a descriptive term in a patent was explored. In this Easter post, the use of another common shape, the egg is explored. There are multiple ways of describing as being egg-shaped, the most obvious being “egg-shaped” but three other options are: ovoid, ovate, and oviform. The most popular of these is “ovate” found in the descriptions in 19241 patents, and in the claims of 386 patents.

Obviousness may not be established using hindsight or in view of the teachings or suggestions of the inventor. Para-Ordnance Mfg., Inc. v. SGS Importers Int’l, Inc., 73 F.3d 1085, 1087, 37 U.S.P.Q.2d 1237, 1239 (Fed. Cir. 1995), citing W.L. Gore & Assocs., Inc. v. Garlock, Inc., 721 F.2d 1540, 1551, 1553, 220 USPQ 303, 311, 312-13 (Fed.Cir.1983), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 851, 105 S.Ct. 172, 83 L.Ed.2d 107 (1984).

Hindsight is inherent in the patent examination process. Examiner’s look at what the inventor claims, and with this information look for prior art to determine whether or not the claimed invention is obvious, flirting with “tempting but forbidden zone of hindsight.” See, Loctite Corp. v. Ultraseal Ltd., 781 F.2d 861, 873, 228 USPQ 90, 98 (Fed.Cir.1985). The problem of hindsight is exacerbated by modern search technology which allows Examiner to quickly and easily find each and every element of the claimed invention, and all that the is needed is to stitch the individual elements together. Patent law has developed several tools to combat hindsight. First, 35 USC 103 requires obviousness of the invention “as a whole,” so merely finding the elements individually in the prior art does not mean that the invention was obvious. Ruiz v. A.B. Chance Co., 357 F.3d 1270, 69 U.S.P.Q.2d 1686 (Fed. Cir. 2004). Second, there is the requirement that there be some reason to modify or combine the prior art. Ruiz v. A.B. Chance Co., 357 F.3d 1270, 69 U.S.P.Q.2d 1686 (Fed. Cir. 2004). Without some reason the modification/combination is not obvious, and neither is the invention. Finally, there are objective indicia of non-obvious, often called “secondary considerations,” that guard against the hindsight reconstruction of the invention. See, In re Sernaker, 702 F.2d 989, 996, 217 USPQ 1, 7 (Fed.Cir.1983).

When confronted with a hindsight reconstruction, there are a number of colorful descriptions of hindsight that can help frame the argument:

Using the Claims as a Frame, and the Prior Art as a Mosaic. In W.L. Gore & Assocs., Inc. v. Garlock, Inc., 721 F.2d 1540, 1551, 1553, 220 USPQ 303, 311, 312-13 (Fed.Cir.1983), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s finding of obviousness, noting that “[t]he result is that the claims were used as a frame, and individual, naked parts of separate prior art references were employed as a mosaic to recreate a facsimile of the claimed invention.” 721 F.2d at 1551, 220 USPQ at 311.

Using What the Inventor Taught Against its Teacher. Also in W.L. Gore & Assocs., Inc. v. Garlock, Inc., 721 F.2d 1540, 1551, 1553, 220 USPQ 303, 311, 312-13 (Fed.Cir.1983), in reversing the district court’s finding of obviousness, the Federal Circuit explained the problem of hindsight: “To imbue one of ordinary skill in the art with knowledge of the invention in suit, when no prior art reference or references of record convey or suggest that knowledge, is to fall victim to the insidious effect of a hindsight syndrome wherein that which only the inventor taught is used against its teacher.” 721 F.2d at 1553, 220 USPQ at 312-13.

Throwing Metaphorical Darts at a Metaphorical Dartboard. In re Kubin, 561 F.3d 1351, 90 U.S.P.Q.2d 1417 (Fed. Cir. 2009), in affirming a finding of obviousness, the Federal Circuit cautioned that in the situation where a challenger, “merely throws metaphorical darts at a board filled with combinatorial prior art possibilities, courts should not succumb to hindsight claims of obviousness.” See, also, Leo Pharm. Prods., Ltd. v. Rea, 726 F.3d 1346, 107 U.S.P.Q.2d 1943 (Fed. Cir. 2013); In re Cyclobenzaprine Hydrochloride Extended-Release Capsule Patent Litig.(Eurand, Inc. v. Mylan Pharm., Inc.), 676 F.3d 1063, 102 U.S.P.Q.2d 1760 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Collapsing the Obviousness Analysis into a Hindsight-Guided Combination. In Leo Pharm. Prods., Ltd. v. Rea, 726 F.3d 1346, 107 U.S.P.Q.2d 1943 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the Federal Circuit reversed the obviousness determination in a reexamination, finding that “the Board erred by collapsing the obviousness analysis into a hindsight-guided combination of elements.”

A Hindsight Combination of Components Selectively Culled from the Prior Art to fit the Parameters of the Invention. In ATD Corp. v. Lydall, Inc., 159 F.3d 534 , 546 (Fed. Cir. 1998), the Federal Circuit reversed a judgment of invalidity, stating “Determination of obviousness can not be based on the hindsight combination of components selectively culled from the prior art to fit the parameters of the patented invention. There must be a teaching or suggestion within the prior art, or within the general knowledge of a person of ordinary skill in the field of the invention, to look to particular sources of information, to select particular elements, and to combine them in the way they were combined by the inventor.”

Using the Inventor’s Disclosure as a Blueprint. In Interconnect Planning Corp. v. Feil, 774 F.2d 1132, 227 U.S.P.Q. 543 (Fed. Cir.1985), the Federal Circuit vacated the district court’s summary judgment of invalidity, noting that the court reconstructed the invention, using the blueprint of the inventor’s claims, and saying [t]he invention must be viewed not with the blueprint drawn by the inventor, but in the state of the art that existed at the time.” See, also, In re Dembiczak, 175 F.3d 994, 50 U.S.P.Q.2d 1614 (Fed. Cir. 1999); Ecolochem, Inc. v. So. Cal. Edison Co., 227 F.3d 1361, 1371-72 (Fed.Cir.2000);

A Poster Child for Impermissible Hindsight Reasoning. In Otsuka Pharm. Co. v. Sandoz, Inc., 678 F.3d 1280, 102 U.S.P.Q.2d 1729 (Fed. Cir.2012), in affirming the district court’s determination that the claims were not invalid, the Federal Circuit noted that the district court’s careful analysis exposed the Defendants’ obviousness case for what it was — “a poster child for impermissible hindsight reasoning.”

Simplicity is not inimical to patentability. In re Oetiker, 977 F.2d 1443, 24 U.S.P.Q.2d 1443, citing Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Ray-O-Vac Co., 321 U.S. 275, 279, 64 S.Ct. 593, 594, 88 L.Ed. 721 (1944) (simplicity of itself does not negate invention); Panduit Corp. v. Dennison Mfg. Co., 810 F.2d 1561, 1572, 1 USPQ2d 1593, 1600 (Fed.Cir.) (the patent system is not foreclosed to those who make simple inventions), cert. denied, 481 U.S. 1052, 107 S.Ct. 2187, 95 L.Ed.2d 843 (1987). Roberts v. Sears, Roebuck, Co., 723 F.2d 1324, 1334, 221 U.S.P.Q. 504 (7th Cir. 1983)(“[I]ntuitive analysis distorted by the invention’s simplicity and retrospective self-evidence must be avoided. Simplicity is not to be equated with obviousness.”); Chore-Time Equip., Inc. v. Cumberland Corp., 713 F.2d 774, 218 U.S.P.Q. 673 (Fed.Cir. 1983)(“That is not to say that simplicity of the invention, or its ready understandability by a judge, constitute evidence of obviousness.”)

In DatCard Sys., Inc. v. PacsGear, Inc., No. 8:10-cv-01288-MRP, 2013 BL 440221 (C.D.Cal. Mar. 12, 2013), the district court said:

To be sure, the Court’s characterization of the patents-in-suit as “simple” is hardly a clue regarding its opinion regarding their validity under, for example, Section 103 . Patent law lacks a doctrine of simplicity. To be sure, as a matter of logic, technically simple patents are perhaps more vulnerable to obviousness-based invalidity than technically complex patents. But they are not obvious because they are technically simple.

(emphasis added)

But, see, Skee-Trainer, Inc. v. Garelick Mfg. Co., 361 F.2d 895, 150 U.S.P.Q. 7 (8th Cir. 1966)(“[A]lthough the simplicity of a mechanical innovation will not automatically render it unpatentable, simplicity is itself strong evidence that ‘invention’ is lacking.”)

In KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 , 416 , 127 S. Ct. 1727 , 167 L. Ed. 2d 705 (2007), the Supreme Court cemented the role of common sense in the obviousness inquiry, noting that “[r]igid preventative rules that deny factfinders recourse to common sense, however, are neither necessary under our case law nor consistent with it.” The Supreme Court instructed that “[c]ommon sense teaches, however, that familiar items may have obvious uses beyond their primary purposes, and in many cases a person of ordinary skill will be able to fit the teachings of multiple patents together like pieces of a puzzle.” Thus the Supreme Court said that:

When there is a design need or market pressure to solve a problem and there are a finite number of identified, predictable solutions, a person of ordinary skill has good reason to pursue the known options within his or her technical grasp. If this leads to the anticipated success, it is likely the product not of innovation but of ordinary skill and common sense.

550 U.S. at 421; 127 S.Ct. at 1742; 167 L.Ed.2d at 723-4.

After KSR, the Federal Circuit has affirmed the application of common sense in a number of cases. In B/E Aerospace, Inc. v. C&D Zodiac, Inc, 962 F.3d 1373, 1379-80, 2020 U.S.P.Q.2d 10706 (Fed.Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s determination of obviousness of U.S. Patent Nos. 9,073 ,641 and 9,440,742 relating to space-saving technologies for aircraft enclosures such as lavatory enclosures, agreeing with the PTAB that it would have been a matter common sense to modify the prior art. In Perfect Web Techs., Inc. v. Infousa, Inc., 587 F.3d 1324, 92 U.S.P.Q.2d 1849, (Fed. Cir. 2009), the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment of invalidity of U.S. Patent No. 6,631,400 directed to managing bulk e-mail distribution to groups of targeted consumers, affirming the district court application of common sense and noting that common sense has long been recognized to inform the analysis of obviousness if explained with sufficient reasoning. In Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330, 2020 U.S.P.Q.2d 32509 (Fed.Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit affirmed a PTAB decision that relied on common sense to supply a missing claim element, where corroborated expert testimony established that that element was not only in the prior art, but also within the general knowledge of a skilled artisan.

Of course, what is important to prosecutors is combatting the misapplication of common sense in the obviousness inquiry. That is what happened in Arendi S.A.R.L. v. Apple Inc., 832 F.3d 1355, 119 U.S.P.Q.2d 1822 (Fed. Cir. 2016) where the Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB determination that challenged claims of U.S. Patent No. 7,917,843 were obvious, because the Board misapplied the law on the permissible use of common sense in an obviousness analysis. The Federal Circuit identified at least three caveats to note in applying “common sense” in an obviousness analysis: First, common sense is typically invoked to provide a known motivation to combine, not to supply a missing claim limitation. Second, as in Perfect Web, when common sense is invoked to supply a limitation that was admittedly missing from the prior art, the limitation in question must be unusually simple and the technology particularly straightforward. Third, references to “common sense”—whether to supply a motivation to combine or a missing limitation—cannot be used as a wholesale substitute for reasoned analysis and evidentiary support, especially when dealing with a limitation missing from the prior art references specified. The Federal Circuit said that the Board relied upon conclusory statements and unspecific expert testimony in drawing its conclusion that the invention would have been “common sense.” Because the application of “common sense” was conclusory and unsupported by substantial evidence, the missing limitation was not a “peripheral” one, and there was nothing in the record to support the Board’s conclusion that supplying the missing limitation would be obvious to one of skill in the art, the Federal Circuit reversed the Board’s finding of unpatentability.

In DSS Tech. Mgmt., Inc. v. Apple Inc., 885 F.3d 1367, 126 U.S.P.Q.2d 1084 (Fed. Cir.2018), the Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s determination that the challenged claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,218,290 were invalid for obviousness, because the Board did not provide a sufficient explanation for its conclusions, and because it could not glean any such explanation from the record.

The PTAB invoked the “ordinary creativity” which the Federal Circuit said was no different from the reference to “common sense” that it considered in Arendi. The Board relied on a gap-filler—”ordinary creativity” instead of “common sense”—to supply a missing claim limitation. The Federal Circuit said that in cases in which “common sense” is used to supply a missing limitation, as distinct from a motivation to combine, the search for a reasoned basis for resort to common sense must be searching. The Federal Circuit said that the Board’s reliance on “ordinary creativity” calls for the same “searching” inquiry. The Federal Circuit found that the Board’s decision did not satisfy the standard set forth in Arendi. The full extent of the Board’s analysis is contained in a single paragraph. In reaching its conclusion that the missing element would have been obviousness, the Board made no citation to the record, referring instead to the “ordinary creativity” of the skilled artisan. This was not enough to satisfy the Arendi standard.

In re Van Os, 844 F.3d 1359, 121 U.S.P.Q.2d 1209 (Fed. Cir. 2017), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the PTAB affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of Van Os’ claims. The Federal Circuit said that it has repeatedly explained that obviousness findings grounded in “common sense” must contain explicit and clear reasoning providing some rational underpinning why common sense compels a finding of obviousness. ” The Federal Circuit said that “[a]bsent some articulated rationale, a finding that a combination of prior art would have been ‘common sense’ or ‘intuitive’ is no different than merely stating the combination ‘would have been obvious.'” The Federal Circuit concluded that “Such a conclusory assertion with no explanation is inadequate to support a finding that there would have been a motivation to combine. This type of finding, without more, tracks the ex post reasoning KSR warned of and fails to identify any actual reason why a skilled artisan would have combined the elements in the manner claimed.”

When faced with an obviousness rejection based upon “common sense” or “ordinary creativity” or “intuition,” it is important to note that these are not a substitute for reasoned analysis and evidentiary support. This is especially true when dealing with a limitation missing from the prior art references specified. Demand this reasoned analysis where it is lacking.

Shamrock-shaped is an apt descriptor for the decoration of the day, but it is also a useful descriptor of a multi-lobed configuration. For example, in U.S. Patent No. 7,784,624, it was an apt descriptor for the shape of opening of the slot 35 which was designed to hold three bats:

It was also used to describe the shape of the catheter passageway in U.S. Patent No. 7,207,981; the cross section of the front part 15 of a bone nail in U.S. Patent No. 9,375,241:

or the three-leaf shamrock shape of the cartridge enlargement unit 610 in U.S. Patent No. 10,016,703:

or the shamrock-shaped opening in U.S. Patent No. 6,595,665:

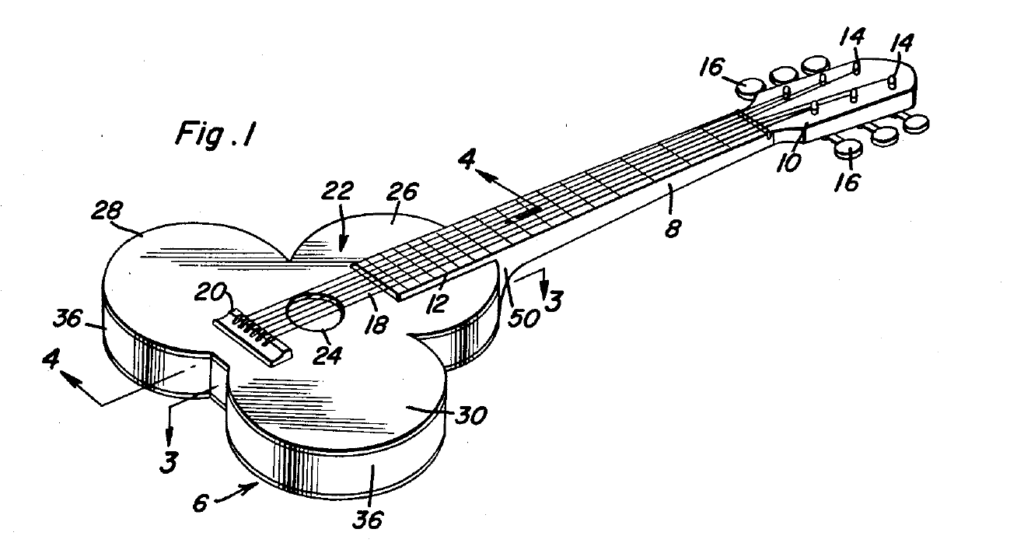

or the shamrock-shaped of body 6 of the musical instrument in U.S. Patent No. 3,188,902:

Analogizing a shape of a component to a commonly known object , such as a shamrock, is a convenient and concise way of describing an embodiment of an invention.

In Gillette Co. v. S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc., 919 F.2d 720, 16 U.S.P.Q.2d 1923 (Fed. Cir. 1990), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s determination that U.S. Patent No. 3,541,581 on a shaving preparation was not invalid under 35 USC 103.

The Federal Circuit rejected Gillette’s obviousness argument as based upon hindsight, quoting from Milton’s Paradise Lost:

The invention all admired, and each how he

To be the inventor missed; so easy it seemed,

Once found, which yet unfound most would have thought,

Impossible!

PARADISE LOST, Part VI, L. 478-501

One of the first requirements of patentability is the utility requirement of 35 USC 101: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” Since something that doesn’t work is not useful, the short (and correct) answer is no, you cannot patent something that does not work.

While the USPTO is not supposed to issue patents on technology that doesn’t work, the Office is not always able to identify non-functioning technology. To be sure, if the disclosure is implausible, an Examiner would reject the application for failure to comply with the enablement requirement of 35 USC 112 (a): “The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains . . . to make and use the same.” Moreover, if the Examiner is suspicious, then Examiner can require the applicant to provide a working model: “The Director may require the applicant to furnish a model of convenient size to exhibit advantageously the several parts of his invention.” 35 U.S.C. 114.

Where the applicant tips off the Examiner, for example with an crazy title or a deficient disclosure, the USPTO will likely reject the application.

However, not all applicants are accommodating enough to flag their disclosures as inoperative. Thus patents do issue that might not have with greater scrutiny. For example, U.S. Patent No. 6,362,718 on a Motionless Electromagnetic Generator, purportedly covers “a magnetic generator used to produce electrical power without moving parts, and, more particularly, to such a device having a capability, when operating, of producing electrical power without an external application of input power.” Interestingly, there is a U.S. patent classification (415/916) for perpetual motion, and ever more interestingly, in addition to 239 published applications, there are 27 issued patents in the class!

A better question than “can you patent inoperative technology” would be: “why would you want to?” No one can infringe a patent on technology that does not work, but enforcement is not always the ultimate goal for a patent. An issued patent is a sort of endorsement of the disclosed technology, and that endorsement alone may be sufficient reason to pursue a patent. However the issued patent is only an endorsement that the disclosure is novel and non-obvious, and not an endorsement of the technology per se.

In Intel Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., [2020-1828, 2020-1867] (December 28, 2021), the Federal Circuit vacated the Board’s decision that claims 1–9 and 12 of U.S. Patent No. 8,838,949 were not unpatentable, because the PTAB failed to tie its construction of the phrase “hardware buffer” to the actual invention described in the specification. The Federal Circuit also vacated the Board’s decision that claims 16 and 17 were not unpatentable, because the Board failed to determine for itself whether there is sufficient corresponding structure in the specification to support the means-plus-function limitations in those claims to determine whether they are sufficiently definite to consider their validity. The ‘949 patent addresses a system with multiple processors, each of which must execute its own “boot code” to play its operational role in the system.

The Federal Circuit said that it was clear from the claim language that “hardware buffer” has meaning, but it is unclear what that meaning was. The Federal Circuit said that there is no definition to be found in the intrinsic evidence, and the determination of that meaning depends on understanding what the intrinsic evidence makes clear is the substance of the invention—what the inventor “intended to envelop.” The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board did not do enough to reach and articulate that understanding, and its claim construction is therefore wanting. The Federal Circuit explained that what was needed, then, was an analysis of the specification to arrive at an understanding of what it teaches about what a “hardware buffer” is, based on both how it uses relevant words and its substantive explanations. In this crucial respect, the Board fell short in its analysis here, and we think the Board is better positioned

than we are to correct the deficiencies.

The Federal Circuit noted that the Board’s construction was entirely a negative one—excluding “temporary” buffers. The Federal Circuit said that although there is no per se rule against negative constructions, which in some cases can be enough to resolve the relevant dispute, the Board’s construction in the present case was inadequate. It was not clear what precisely constitutes a

“temporary buffer” as recited in the Board’s construction.

With respect to claims 16 and 17, there is no dispute that claim 16 (and hence dependent claim 17) contains terms that are in means-plus-function format governed by 35 U.S.C. § 112(f). Because Intel agreed with the Board’s suggestion in the institution decision that two of the means-plus-function terms

in claim 16 were indefinite for lack of supporting structure, the Board concluded that Intel’s statement necessarily meant that Intel, as the petitioner, had not met its burden to demonstrate the unpatentability of those claims.

The Federal Circuit held that this was error and that a remand was required, because the Board did not

decide for itself whether required structure is present in the specification or whether, even if it was not, the absence of such structure precludes resolution of Intel’s prior-art challenges. The Federal Circuit added that to avoid confusion going forward, the Board should, in IPRs where Impossibility because indefiniteness applies, clearly state that the final written decision does not include a determination of patentability of any claim that falls within the impossibility category.