In Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Erie Indemnity Company, [2016-1128, 2016-1132] (March 7, 2017), the Federal Circuit affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded in part the district court’s decision finding all claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,510,434, 6,519,581 and 6,546,002 ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, and the infringement claim of the ’581 patent for lack of standing.

Lack of Standing

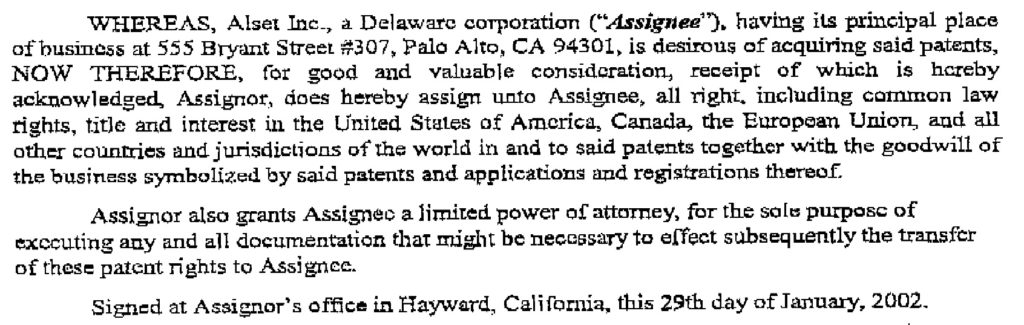

The rights of the parent application of the ‘581 patent, together with “all continuations” (including the ‘581 patent application, which was pending at the time, were assigned to ALLAdvantage.com. AllAdvantage.com then assigned various patent (including the parent of the ‘581 patent) to Alset. Although this agreement expressly identified the various patents and pending applications subject to assignment—including

the ’581 parent and several of its pending foreign patent application counterparts—it did not explicitly list the ’581 patent’s then-pending application. The assignment generally provided:

The Federal Circuit concluded that the Alset Agreement did not include an assignment of rights to the ’581 patent and affirmed the district court’s Rule 12(b)(1) dismissal. The Federal Circuit rejected the argument that the language implicitly included the ‘581 patent application. Applying California contract law, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s conclusion that there is no ambiguity within the Alset Agreement that could render it reasonably susceptible to an interpretation that the ‘581 patent application was transferred. The fact that Alset recorded the assignment at the PTO, represented in a terminal disclaimer that it owned all the rights to the ’581 patent, and filed updated power of attorneys and paid the ’581 patent’s issuance fee. The Federal Circuit said that although this evidence may lead one to reasonably conclude that Alset believed it owned the ’581 patent application at some later point in time, it would be error to rewrite the parties’ agreement to include that which was plainly not included. The fact that other pending applications were expressly listed also did not help plaintiff’s cause.

Because the Federal Circuit agreed that plaintiff lacked standing to sue under the ‘581 patent, it vacated the finding that the ‘581 patent was invalid under §101.

Don’t Take Your Eye Off the Ball

Conveying a pending patent application should be routine. And perhaps because it was so routine is the reason that things went wrong. If you want to assign a pending application, it is a probably a good idea to specifically identify that application. If you want to include all continuations, divisionals, and continuations in part, than it is a good idea idea to say “including all continuations, divisionals, and continuations in part” rather than “together with the goodwill of the business symbolized by said patents and applications and registrations thereof.”

Invalidity Under §101

As to the ‘434 patent, which contained twenty-eight claims relating to methods and apparatuses that use an index to locate desired information in a computer database: Under step one of the Mayo/Alice test the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the invention is drawn to the abstract idea of “creating an index and using that index to search for and retrieve data. The Federal Circuit noted that it had previously held patents ineligible for reciting similar abstract concepts that merely collect, classify, or otherwise filter data. Under step two of the Mayo/Alice test the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that they lack an “inventive concept” that transforms the abstract idea of creating an index and using that index to search for and retrieve data into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea. The fact that the claimed invention employed an index of XML tags was not significant in view of the patent’s admission that such tags are known. Moreover limiting an abstract idea to a particular field does not make the idea any less abstract. The Federal Circuit concluded that the claimed computer functionality can only be described as generic or conventional.

As to the ‘002 patent, which contained 49 claims relating to systems and methods for accessing a user’s remotely stored data and files:

Under step one of the Mayo/Alice test the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the claims are drawn to the idea of “remotely accessing user specific information. Under step two of the Mayo/Alice test, the Federal Circuit concluded that the claims recite no “inventive concept” to transform the abstract idea of remotely accessing user-specific information into a patent eligible application of that abstract idea. Rather, the Federal Circuit said that the claims merely recite generic, computer implementations

of the abstract idea itself.