In Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc., [2018-1638, 2018-1639, 2018-1640, 2018-1641, 2018-1642, 2018-1643] (July 20, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s denial of the Tribe’s motion to terminate on the basis of sovereign immunity.

In an attempt to shelter its patents from IPR attack, Allegan assigned them to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, who Allergan hoped could assert sovereign immunity to post grant challenges.

The Tribe argued that tribal sovereign immunity applies in IPR under FMC, because like the proceeding in FMC, an IPR is a contested, adjudicatory proceeding between private parties in which the petitioner, not the USPTO, defines the contours of the proceeding. Mylan argued that sovereign immunity does not apply to IPR proceedings because they are more like a traditional agency action — the Board is not adjudicating claims between parties but instead is reconsidering a grant of a government franchise. Mylan further argued that even if the Tribe

could otherwise assert sovereign immunity, its use here is an impermissible attempt to “market an exception” from the law and non-Indian companies have no legitimate interest in renting tribal immunity to circumvent the law. Finally, Mylan argued that the assignment to the Tribe was a sham, and the Tribe waived sovereign immunity by suing on the patents.

The Federal Circuit said that an IPR is neither clearly a judicial proceeding instituted by a private party nor clearly an enforcement action brought by the federal government, noting that in Oil States the Supreme Court said IPR is “simply a reconsideration of” the

PTO’s original grant of a public franchise.

Ultimately, several factors convinced the Federal Circuit that IPR is more like an agency enforcement action than a civil suit brought by a private party, and and thus tribal immunity is not implicated. First, although the Director’s discretion in how he conducts IPR is significantly constrained, he possesses broad discretion in deciding whether

to institute review. Although this is only one decision, it embraces the entirety of the proceeding. If the Director decides to institute, review occurs. If the Director decides not to institute, for whatever reason, there is no review. In making this decision, the Director has complete discretion to decide not to institute review. The Director bears the political responsibility of determining which cases should proceed. While he has the authority not to institute review on the merits of the petition, he could deny review for other reasons such as administrative

efficiency or based on a party’s status as a sovereign. Therefore, if IPR proceeds on patents owned by a tribe, it is because a politically accountable, federal official has authorized the institution of

that proceeding. In this way, IPR is more like cases in which an agency chooses whether to institute a proceeding on information supplied by a private party. According to FMC, immunity would not apply in such a proceeding.

The Federal Circuit added that the role of the parties in IPR suggests immunity does not apply in these proceedings. Once an IPR has been initiated, the Board may choose to continue review even if the petitioner chooses not to participate, which reinforces the view that IPR is an act by the agency in reconsidering its own grant of a public franchise.

The Federal Circuit also pointed out that although there are certain

similarities with the FRCP, the differences are substantial. Further a patent owner can seek to amend its patent claims during the proceedings, an option not available in civil litigation.

Finally, while the USPTO has the authority to conduct reexamination proceedings that are more inquisitorial and less adjudicatory than IPR, this does not mean that IPR is thus necessarily a proceeding in which Congress contemplated tribal immunity to apply. The mere existence of more inquisitorial proceedings in which immunity does not apply does not mean that immunity applies in a different type of proceeding

before the same agency.

Because it concluded that tribal sovereign immunity cannot be asserted in IPR, the Federal Circuit did not reach the parties’ other arguments.

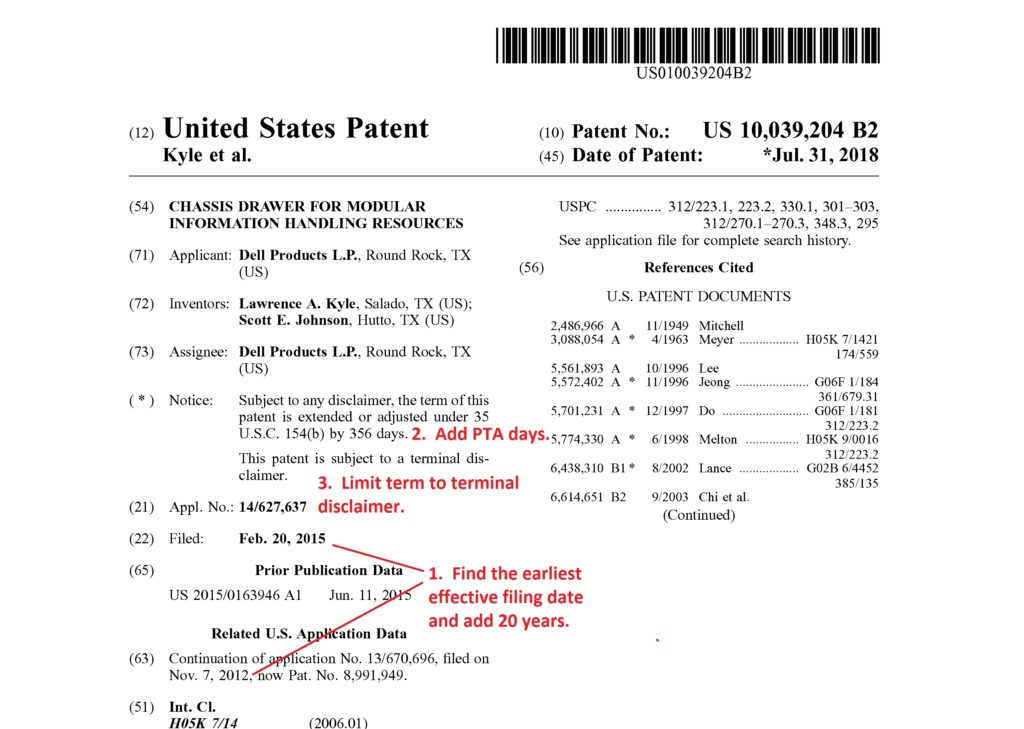

The vast majority are governed by 35 USC 154(a)(2), which provides: