On February 1, 1938, U.S. Patent P269 issued to Luther Burbank on a Rose:

Brrr!

With temperatures in parts of the U.S. lower than we have seen in decades, it seems appropriate to recognize the inventors whose work help us brave this weather weather.

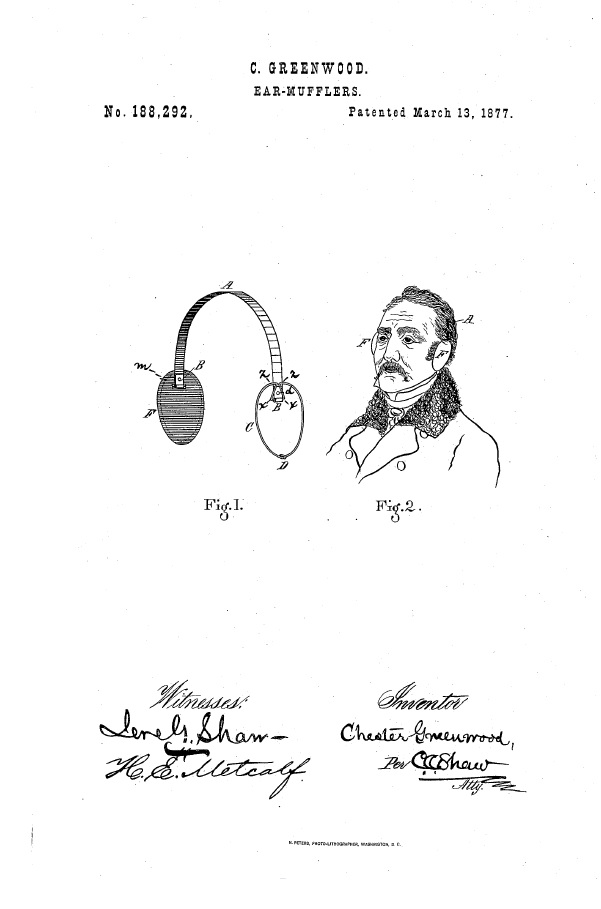

First and foremost is Chester Greenwood, inventor of ear muffs, whose U.S. Patent No. 188,292, issued March 13, 1877:

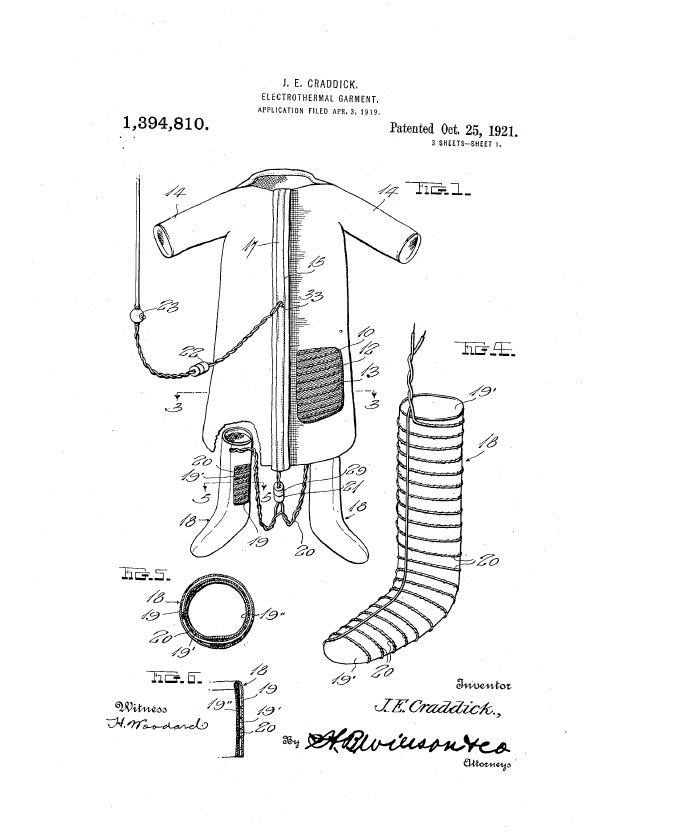

Our thanks should also go to Joel Craddick, whose U.S. Patent No. 1,394,810, issued October 1921, on an “Electrothermal Garment” — among the earliest electrically heated clothing.

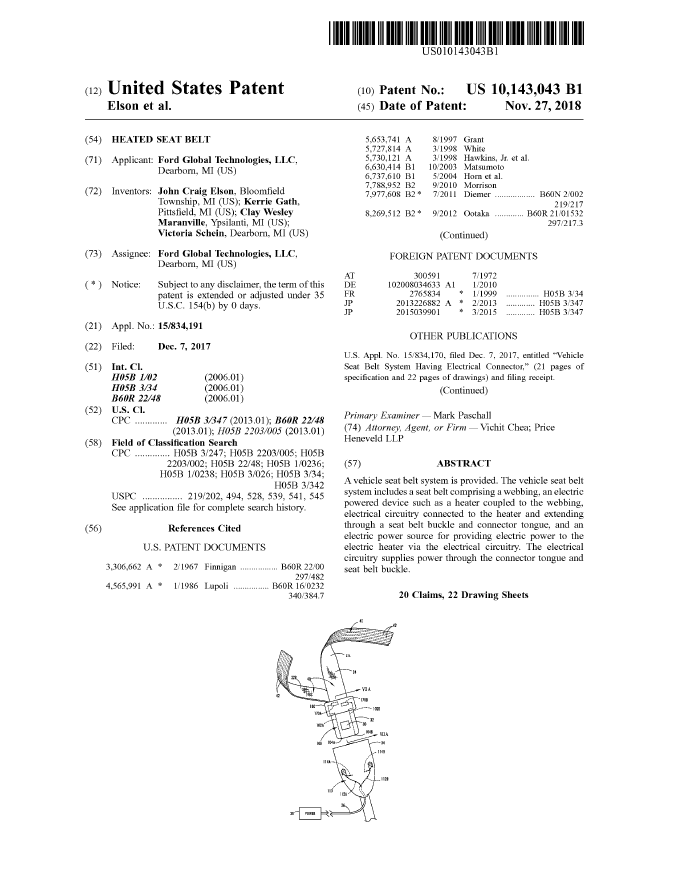

However, inventors’ work on protecting us from the cold continues to this day, and John Elson, Kerrie Gath, Clay Maranville, and Victoria Schein, were issued U.S. Patent No. 10,143,043 on a “Heated Seat Belt.” While when I am backing out of my driveway at 1° F I will be wearing a jacket so thick that I won’t be able to tell whether or not the seat belt is warm, I can still appreciate their thinking of us.

John Elson, Kerrie Gath, Clay Maranville, and

Victoria Schein’s U.S. Patent on a Heated Seat Belt.

Working Backwards with the Benefit of Hindsight, Does not Render Compound Obvious

In Amerigen Pharmaceuticals Limited v. UCB Pharma GmbH, [2017-2596] (January 11, 2019), the Federal Circuit claims affirmed the PTAB’s determination that claims 1–5 and 21–24 of U.S. Patent 6,858,650 on an antimuscarinic drug marketed as Toviaz® to treat urinary incontinence were not unpatentable as obvious.

The Federal Circuit noted that its review of a Board decision is limited. The Federal Circuit reviews the Board’s legal determinations de novo, and the Board’s factual findings underlying those determinations for substantial evidence. The Federal Circuit explained that a finding is supported by substantial evidence if a reasonable mind might accept the evidence as adequate to support the finding.

The Federal Circuit agreed that the Board did not legally err and that substantial evidence supports the Board’s findings. As to Amerigen’s argument that a person of ordinary skill would have been motivated to modify 5-HMT to increase its lipophilicity, the Federal Circuit said that a a reasonable fact finder could have weighed UCB’s expert testimony over Amerigen’s, and concluded that substantial evidence supported the Board’s finding that a person of ordinary skill would not have been motivated to modify 5-HMT to increase its lipophilicity.

As to Amerigen’s argument that increasing lipophilicity “in and of itself” (i.e., independent of bioavailability concerns) would have motivated a person of ordinary skill to modify 5-HMT, the Federal Circuit noted that Amerigen did not present this theory to the Board, and could point to no evidence in the record to support of it, and did not explain why a skilled artisan would modify a drug to increase its lipophilicity independent of bioavailability.

As to Amerigen’s argument that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to modify 5-HMT because 5-HMT was patented at the time of invention, the Federal Circuit noted that there was no indication that such a motivation was sufficient to prove that the claimed compounds would have been obvious. The Federal Circuit said:

Any compound may look obvious once someone has made it and found it to be useful, but working backwards from that compound, with the benefit of hindsight, once one is aware of it does not render it obvious.

Any compound may look obvious once someone has made it and found it to be useful, but working backwards from that compound, with the benefit of hindsight, once one is aware of it does not render it obvious.

The Federal Circuit said it considered Amerigen’s remaining arguments, and not find them persuasive, and thus affirmed the Board’s decision.

USPTO Cannot Reduce PTA for Time Where Applicant Could Not Act

In Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., v. Iancu, [2017-1357] (January 23, 2019), the Federal Circuit reversed summary judgment for the USPTO because the denial of patent term adjustment in this case went beyond the period during which the applicant failed to undertake reasonable efforts and thereby exceeded the limitations set by the patent term adjustment statute.

On February 22, 2011, Supernus filed an RCE in response to a final rejection. On September 11, 2012, Supernus received a letter from its European patent counsel disclosing the EPO notification of an opposition against a European counterpart application on August 21, 2012. Seventy-nine days later, or 100 days from the EPO notification of the Opposition,

on November 29, 2012, Supernus submitted a supplemental IDS.

On September 10, 2013, the USPTO issued a first Office Action responding to Supernus’s RCE. On January 10, 2014, Supernus filed a response. On February 4, 2014, the USPTO issued a Notice of Allowance. On June

10, 2014, U.S. Patent No. 8,747,897 issued, reflecting a PTA of 1,260 days (2146 PTO delay days less 886 applicant delay days). 646 of the applicant delay days were for the period between the filing of the RCE and the filing of the supplemental IDS, although as Supernus pointed out, it could not file the supplemental IDS until the filing of the Opposition.

The USPTO stood by its interpretation of the PTA statute and corresponding regulations, bolstered by Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Lee, denying Supernus request for consideration, and the district court affirmed the USPTO granting summary judgment. However, the Federal Circuit found Gilead was distinguishable because it involved a period of time where Gilead could have filed an IDS but did not. In the instant case, Supernus could not have disclosed the Opposition that was the subject matter of the supplemental IDS until the opposition had actually occurred.

The Federal Circuit said that any reduction to PTA shall be “equal to the

period of time during which the applicant fail[s] to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution of the application” citing 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(C)(i). The Federal Circuit said that the USPTO would exceed its statutory authority if it reduced PTA for longer than the time period during which the applicant failed engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution of the application.

Supernus had conceded the 100 days delay in filing filing the supplemental IDS, but as to the remaining 546 days, these could not properly be attributed to applicant delay because they were before the event that precipitated the need to file the supplemental IDS.

Because Gilead involved different facts and a different legal question, Gilead was not controlling, and the district court erred in granting summary judgment, and because the proper framework for determining PTA was clear from the statute, the Federal Circuit reversed the grant of summary judgment.

While applicants must act diligently to preserve PTA, the statute does not permit the USPTO to take away PTA for periods of time where applicant could not take action. Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Lee allows the USPTO to reduce PTA without having to prove that applicant inaction cause a delay, but there still has to be applicant inaction for a reduction in PTA.

It is disheartening that the USPTO always seems to be on the opposite side of applicants in PTA disputes, never seeming to give applicants (its customers) a break.

If a Sale Occurs in a Forest and No One is There to See it, is it Still a Sale? Yes.

In Helsinn Healthcare S.A. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., the Supreme Court affirmed the Federal Circuit that a non-disclosing sale is prior art under post AIA 35 USC §102(a)(1).

35 USC §102(a)(1) states:

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless . . . the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.” 35 U. S. C. §102(a)(1)

At issue was whether or the sale had to be one “available to the public,” given the language “or otherwise available to the public.” The Supreme Court observed that every patent statute since 1836 has included an on-sale bar. including the one immediately prior to the AIA. The AIA retained the on sale bar, and added a catch-all phrase. The Supreme Court concluded that this addition was not enough to change the meaning of “on sale.”

The Court noted that while it had never addressed the precise question presented, its precedents suggest that a sale or offer of sale need not make an invention available to the public. In light of this settled pre-AIA precedent on the meaning of “on sale,” the Court presumed that when Congress reenacted the same language in the AIA, it adopted the earlier judicial construction of that phrase. The new §102 retained the exact language used in its predecessor statute (“on sale”) and, as relevant here, added only a new catchall clause (“or otherwise available to the public”). The Court appeared to agree that the addition of a catchall phrase was a fairly oblique way of attempting to overturn a settled body of law.

The Supreme Court rejected Helsinn’s argument that this construction read out “otherwise” from the statute, and that the associated-words canon requires us to read “otherwise available to the public” to limit the preceding terms in §102 to disclosures that make the claimed invention available to the public. The Court first noted that that the language had acquired a well-settled judicial interpretation, and that the phase “otherwise available to the public” simply captures material that does not fit neatly into the statute’s enumerated categories but is nevertheless meant to be covered. The Court said that “Given that the phrase ‘on sale’ had acquired a well-settled meaning when the AIA was enacted, we decline to read the addition of a broad catchall phrase to upset that body of precedent.”

While the Supreme Court affirmed the Federal Circuit, it did not seem to agree with their rationale, which depended upon the fact that the sale itself was public, even if it was non-disclosing. By extension, it also seems that the Supreme Court would not limit “public use,” another phrase with a well-settled meaning, to disclosing public uses.

Nearly eight years after the passage of the AIA, we finally have some clarity on what is prior art under the statute. At the very least, it looks like the USPTO is going to have to rewrite MPEP 2152.02(d), and hopefully no patents improperly issued because of the Office’s misunderstanding of post-AIA prior art.

Our Own Oddities

For fifty years between 1940 and 1990, The St. Louis Post Dispatch had a section in its comics pages titled Our Own Oddities, featuring unusual things from around the St. Louis metropolitan area. There are a number of patent “oddities,” and while they may not be as astounding as a Nixon-shaped potato they are nonetheless cataloged below.

The First Patent

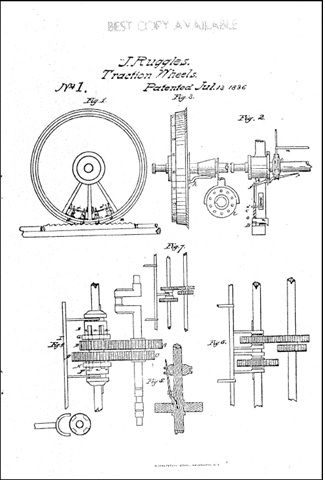

The first patent, as most patent attorneys know, was issued to Samuel Hopkins on July 31, 1790, on a method of making potash and pearlash. However U.S. Patent No. 1 issued to J. Ruggles on July 13, 1836, when it finally occurred to someone in the Patent Office to start numbering these things. Approximated 10,000 unnumbered patents, often call the X-series of patents were issued prior to U.S. Patent No. 1.

First Patent to a Female Inventor

The first patent to issue to a female inventors is believed to be one of the aforementioned X-series patents, No. 1041X on Weaving Straw with Silk Thread, issued to Mary Kies on May 5, 1809.

First Patent to an African-American Inventor

The first patent to issue to an African-American is believed to be one of the aforementioned X-series patents, No. 3306X on Dry Scouring of Clothes, issued to Thomas L. Jennings on March 3, 1821.

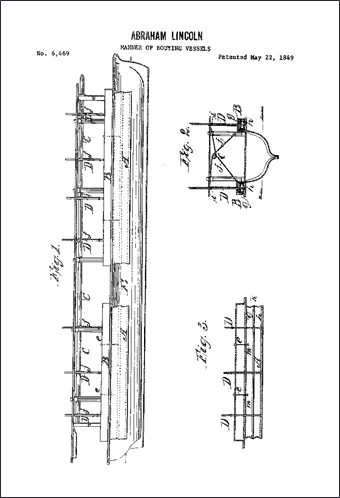

Only Patent to a President

The only patent issued to a president is U.S. Patent No. 6,469 on a Manner of Bouying Vessels, issued to Abraham Lincoln on May 22, 1849.

Shortest Patent Claim

The scope of a patent is defined by its claims, and there are a number of two-word patent claims, including Glenn Seaborg’s U.S. Patent No. 3,156,523, issued November 10, 1964, claiming: “1. Element 95,” and his U.S. Patent No. 3,164,462, issued December 15, 1964, claiming “1. Element 96.”

However there are in fact several patents with a one-word claim, including Lloyd H. Conover’s U.S. Patent No. 2,699,054, issued January 11, 1955, whose claim 2 simply recites “Tetracycline.” For another example, check out claims 12-19 of U.S. Patent No. 3,775,489.

Longest Patent Claim

Among the longest patent claims is one found in U.S. Patent No. 6,953,802, Beta-Amino Acid Derivatives-Inhibitors of Leukocyte Adhesion Mediated by VLA-4, it contains over 17,000 words, spanning from column 59, line 27 to column 101, line 30.

Most Claims in an Application

The record for most claims in an application is US Published Application No. 20030173072 for Forming Openings in a Hydrocarbon Containing Formation Using Magnetic Tracking. As published it contained 8,958 claims, issuing as U.S. Patent No. 6,991,045 with a more modest but still impressive 90 claims.

Most Claims in a Patent

The record for most claims in a patent is U.S. Patent No. 6,684,189 Apparatus and Method Using Front-end Network Gateways and Search Criteria for Efficient Quoting at a Remote Location, with 887. Runners up are U.S. Patent No. 5,095,054 for Polymer Compositions Containing Destructurized Starch, with just 868 claims, and U.S. Patent No. 7,096,160 System and Method for Measuring and Monitoring Wireless Network Performance in Campus and Indoor Environments, with a paltry 803 claims.

Longest Patent Application

The longest patent application is U.S. Patent Application No. US20070224201A1 for Compositions and Methods for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Tumor with 7,154 pages.

Longest Patent

The longest patent is U.S. Patent No. 6,314,440 for Pseudo Random Number Generator, with 3333 pages, 3272 of which are drawings). Slightly shorter, but much wordier is U.S. Patent No. 5,146,591 has more than one million words on 3071 pages.

Shortest Patent

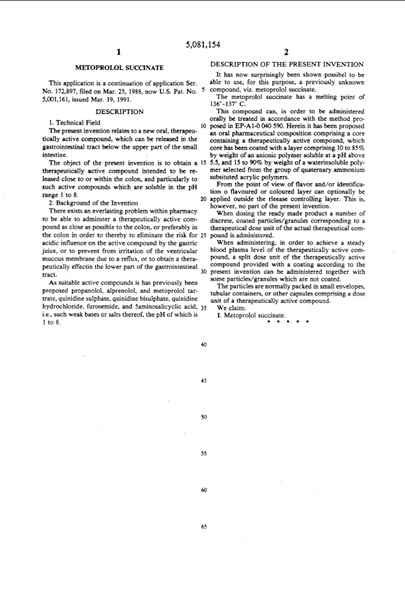

U.S. Patent No. 5,081,154 for Metroprolol Succinate is one half page long (about 70 lines).

Most Drawings in an Application

U.S. Patent Application No. 20070224201A1 has 6881 sheets of drawings.

Shortest Patent Term

U.S. Patent Nos. 6,211,625; 6,211,619; 6,198,228; 6,144,445; 7,604,811 (and others) had a term of “0” — each expired before it issued!

Longest Patent Term

U.S. Patent No. 6,436,135, was filed in 1974, and issued in 2002, and thus won’t expire until this year (2019), 45 years after it was filed.

Most Co-Inventors

U.S. Patent Nos. 7,013,469 and 7,017,162 for Application Program Interface for Network Software Platform have 51 coinventors.

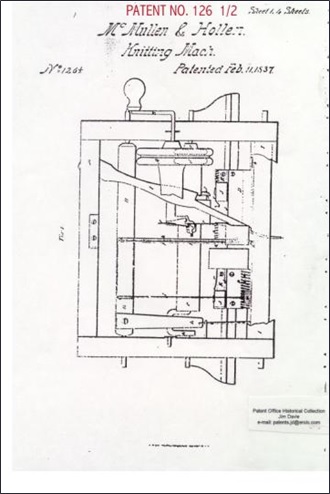

Strangest Patent Number

The U.S. has issued several “fractional” patents, including U.S. Patent No. 126 ½ on February 11, 1837, and U.S. Patent No. 3,262,124 ½ on July 19, 1966.

Most Popular

U.S. Patent No. 4,723,129 has been cited in 2,372 subsequent patents.

Most Prior Art

U.S. Patent No. 9.535,563 cites 7800 references; U.S. Patent No. 8,612,159 on Analyte Monitoring Device and Methods of Use cites 3,594 items of prior art on 32 pages.

Largest Patent Family

U.S. Patent No. 5,095,054 has 380 family members.

Longest Inventor Name

U.S. Patent No. 7,531,342 names Osterhaus Albertus Dominicus Marcellinus Erasmus as inventor with 44 characters in his name.

Most Enigmatic Title

U.S. Application 20020174863 is entitled “Unknown”

Simplest Drawing

U.S. Patent No. 448,647 issued March 24, 1891, on a Tooth Pick.

Federal Circuit Remands WesternGeco’s Damaged Damages Case

In WesternGeco L.L.C., v. Ion Geophysical Corporation, [2013-1527, 2014-1121, 2014-1526, 2014-1528](January 11, 2019), the Federal Circuit, on remand from the Supreme Court, remanded to the district court.

The Supreme Court held that WesternGeco’s damages award for lost profits was a permissible domestic application of 35 U.S.C. § 284,” reversing the Federal Circuit.

But the Supreme Court did not decide other challenges to the lost profits award. In light of the Supreme Court’s decision and the intervening invalidation of four of the five

asserted patent claims that could support the lost profits award, the Federal Circuit remanded the case to the district court.

Anticipation is the Epitome of Obviousness

In Realtime Data, LLC, v. Iancu, [2018-1154] (January 10, 2019), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s determination that claims 1–4, 8, 14–17, 21, and 28 of U.S. Patent No. 6,597,812 on systems and methods for providing lossless data compression and decompression would have been obvious over the prior art.

Realtime made two primary arguments on appeal: (1) that the Board erred in its determination that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine the teachings of O’Brien and Nelson; and (2) that the Board erred by failing to construe the “maintaining a dictionary” limitation and in finding that O’Brien disclosed the “maintaining a dictionary” limitation.

HP’s primary argument to the Board was that all of the elements of claims 1–4, 8, and 28 were disclosed in O’Brien, a single reference, and it relied on Nelson simply to demonstrate that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood that the string compression disclosed in O’Brien was, in fact, a type of dictionary encoder, the terminology used in the ’812 patent. HP alternatively argued that that Nelson disclosed at least some of the elements in the claims at issue. Because the Board agreed that all of the claim elements could be found in O’Brient alone, the the Board was not required to make any finding regarding a motivation to combine. Had the Board relied upon HP’s alternative argument, it would have been required to demonstrate a sufficient motivation to combine the two references.

While Realtime argues that the use of O’Brien as a single anticipatory reference would have been more properly raised under §102, the Federal Circuit said that it is well settled that “a disclosure that anticipates under § 102 also renders the claim invalid under §103, for ‘anticipation is the epitome of obviousness.’”

The Federal Circuit said that in any event, even if the Board were required to make a finding regarding a motivation to combine O’Brien with Nelson, its finding in this case is supported by substantial evidence. The Federal Circuit noted that a motivation to combine may be found “explicitly or implicitly in market forces; design incentives; the ‘interrelated teachings of multiple patents’; ‘any need or problem known in the field of endeavor at the time of invention and addressed by the patent’; and the background knowledge, creativity, and common sense of the person of ordinary skill.”

On the issue of whether the Board erred in finding that O’Brien disclosed the “maintaining a dictionary” limitation in independent claim 1, Realtime argued that the Board erroneously failed to construe the term “maintaining a dictionary” to include the requirement that the dictionary be retained during the entirety of the data compression unless and until the number of entries in the dictionary exceeds a predetermined threshold, in which case the dictionary is reset. While the words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning, a claim term is read not only in the context of the particular claim in which the disputed term appears, but in the context of the entire patent, including the specification. These claim construction principles are important even in an inter partes review proceeding like this one, in which the claims were properly given the “broadest reasonable interpretation” consistent with the specification.

The Federal Circuit said that the Board’s interpretation was supported by both the claim language itself and the specification. While the term “maintaining a dictionary” is not defined, claim 4 lends meaning to the phrase, and directly mimics the specification. Realtime argued that because the claim recited “comprising” the Board erred by limiting the definition of “maintaining a dictionary.” The Federal Circuit rejected, this argument pointing out that the word “comprising” does not mean that the claim can be read to require additional unstated elements, only that adding other elements to the device or method is not incompatible with the claim.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board did not err in concluding that the claims would have been obvious in view of a single reference, and that the Board did not err in finding that O’Brien disclosed the “maintaining a dictionary” limitation in independent claim 1, and therefore affirmed the Board.

PTAB Reconsideration Did Not Violate Due Process

In AC Technologies S.A., v. Amazon.com, Inc., [2018-1433] (January 9, 2019) the Federal Circuit affirmed the Final Written Decision of the PTAB ruling certain claims of AC Technologies S.A.’s U.S. Patent No. 7,904,680 unpatentable. AC complained that the Board, on reconsideration, invalidated claims based on a ground of unpatentability raised in their petition but not addressed in the original Final Written Decision, arguing that the Board exceeded its authority and deprived it of fair process by belatedly considering this ground.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, noting that precedent mandated that the Board consider all grounds of unpatentability raised in an instituted petition. The Board complied with due process, and AC did not persuade it that the Board erred in either its claim construction or its ultimate conclusions of unpatentability. The Petition contained three grounds, Ground 1 alleged unpatentability giving the claims, and in particular, the term “computer unit” a narrow construction. Grounds 2 and 3 asserted unpatentability over the same reference, giving “computer unit” a broader construction.

The Board invalidated claims based upon Grounds 1 and 2, but not three. When the inconsistency was pointed out on request for rehearing, the Board address Ground 3. The Federal Circuit said that no due process violation occurred here. As AC admits, after the Board decided to accept Amazon’s rehearing request and consider Ground 3, it permitted AC to take discovery and submit additional briefing and evidence on that ground. The Federal Circuit noted that alhough AC did not receive a hearing specific to Ground 3, it never requested one. Had AC desired a hearing, it should have made a request before the Board.

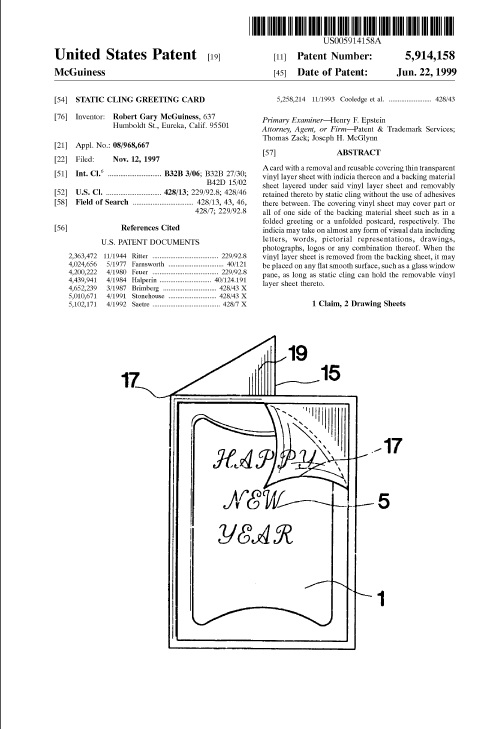

Happy New Year!

Best wishes from everyone at Harness, Dickey for a Happy and Prosperous 2019.