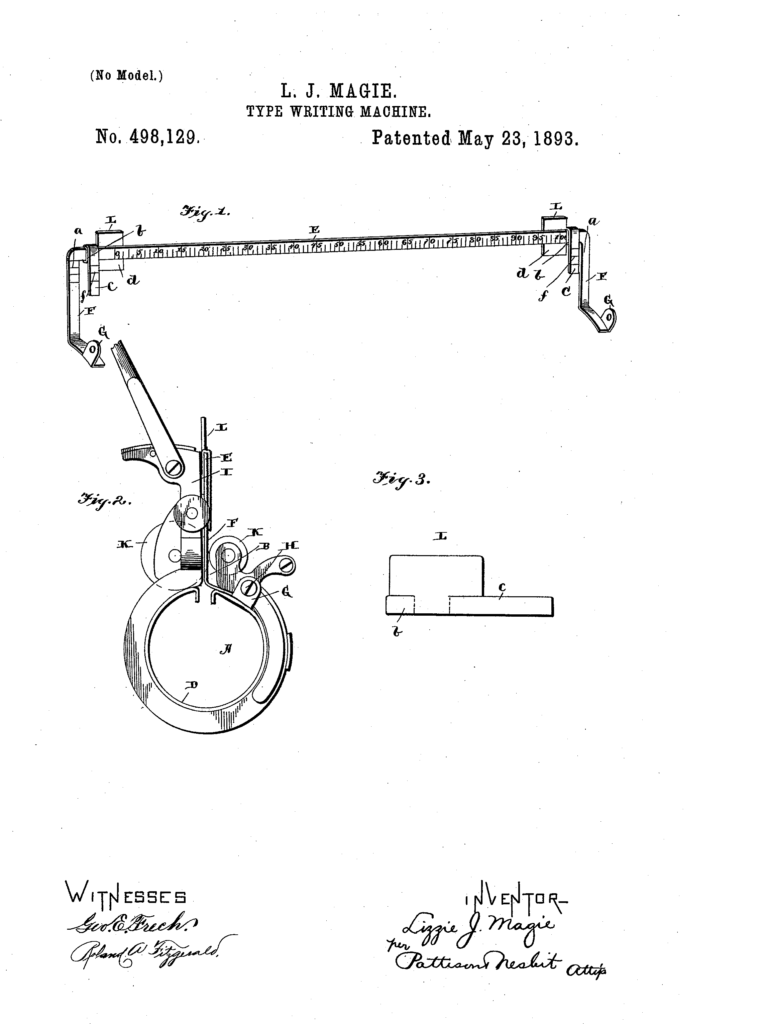

In Salazar v. AT&T Mobility LLC, [2021-2320, 2021-2376] (April 5, 2023), the Federal Circuit affirmed judgment of noninfringement of U.S. Patent No. 5,802,467 describing technology for wireless and wired communications.

Claim 1 of the ‘467 patent required “a microprocessor for generating a plurality of control signals used to operate said system, said microprocessor creating a plurality of reprogrammable communication protocols, for transmission to said external devices wherein each communication protocol includes a command code set that defines the signals that are employed to communicate with each one of said external devices.” The district court construed the court construed “a microprocessor” to mean one microprocessor.”

On appeal, Salazar argued that the court should have interpreted a microprocessor” to require one or more microprocessors, any one of which may be capable of performing each of the “generating,” “creating,” and “retrieving” functions recited in the claims.

The Federal Circuit explained that the indefinite article “a” means “‘one or more’ in open-ended claims containing the transitional phrase ‘comprising.’” The Court said an exception to the general rule that “a” means more than one only arises where the language of the claims themselves, the specification, or the prosecution history necessitate a departure from the rule.” The Federal Circuit further explained that the use of the term “said” indicates that this portion of the claim limitation is a reference back to the previously claimed” term. The claim term “said” is an “anaphoric phrase, referring to the initial antecedent phrase”. The subsequent use of the definite article ‘said’ in a claim to refer back to the same claim term does not change the general plural rule, but simply reinvokes that non-singular meaning.”

The Federal Circuit reviewed prior cases interpreting “a” and noted in particular In re Varma, 816

F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2016), which the district court had explained that the claim term provided certain functions that the “said microprocessor” must be “necessarily configured to perform as well as the structural relationship between ‘said microprocessor’ and other structural elements.” Thus, the district court reasoned, “at least one microprocessor must satisfy all the functional (and relational) limitations recited for ‘said microprocessor.’ On appeal, Salazar’s argued that a correct claim construction would encompass one microprocessor capable of performing one claimed function and another microprocessor capable of performing a different claimed function, even if no one microprocessor could perform all of the recited functions. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, agreeing with the district court that while the claim term “a microprocessor” does not require there be only one microprocessor, the subsequent limitations referring back to “said microprocessor” require that at least one microprocessor be capable of performing each of the claimed functions, which the Court said was “entirely consistent” with it precedents. The Court noted that, as it stated in Varma, for a dog owner to have a dog that rolls over and fetches sticks, it does not suffice that he have two dogs, each able to perform just one of the tasks.