Celebrating the start of a new year and a new decade with patents.

Happy New Year and best wishes for a prosperous 2020 from HDP.

Celebrating the start of a new year and a new decade with patents.

Happy New Year and best wishes for a prosperous 2020 from HDP.

In Persion Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Alvogen Malta Operations LTD., [2018-2361] (December 27, 2019) the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s determination that the asserted claims of U.S. Patent No. 9,265,760 and 9,339,499 entitled “Treating Pain in Patients with Hepatic Impairment” were obvious.

Persion raised four primary challenges to the district court’s obviousness conclusion. First, Persion contended that the district court improperly relied on inherency to conclude that the prior art discloses the pharmacokinetic limitations of the asserted claims. It is long settled that in the context of obviousness, the mere recitation of a newly discovered function or property, inherently possessed by things in the prior art, does not distinguish a claim drawn to those things from the prior art. The Federal Circuit noted that the Supreme Court explained long ago that it is not invention to perceive that the product which others had discovered had qualities they failed to detect.

However, inherency is a high standard, that is carefully circumscribed in the context of obviousness. Inherency may not be established by probabilities or possibilities, and the mere fact that a certain thing may result from a given set of circumstances is not sufficient. Inherency renders a claimed limitation obvious only if the limitation is “necessarily present,” or is “the natural result of the combination of elements explicitly disclosed by the prior art.” The Federal Circuit said “inherency may supply a missing claim limitation in an obviousness analysis” where the limitation at issue is “the natural result of the combination of prior art elements,” and found that was the case here.

Second, Persion argued that the district court improperly relied on pharmacokinetic profiles from drugs other than extended-release single-active-ingredient hydrocodone formulations and from patients other than those with hepatic impairment in reaching its obviousness conclusion. The Federal Circuit found that the district court provided several reasons for its conclusion that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have considered other types of drug products in developing a hydrocodone-only extended-release formulation. In light of the record as a whole, we find no clear error in the district court’s findings on the relevance of combination product data to a person of ordinary skill considering the administration of a hydrocodone-only product.

Third, Persion contended that the district court erred by finding the asserted claims obvious before considering the objective indicia factors. The Federal Circuit found that the district court considered Persion’s evidence of objective indicia together with the other evidence presented at trial on the issue of obviousness. While the district court’s discussion of objective indicia followed its discussion of the asserted prior art, the Federal Circuit found that the substance of the court’s analysis makes clear that it properly considered the totality of the obviousness evidence in reaching its conclusion and did not treat the objective indicia as a mere “afterthought” relegated to rebutting a prima facie case. Overall, the Federal Circuit found no clear error with the district court’s assessment of the objective indicia evidence. Fourth, Persion argued that the district court’s factual findings concerning obviousness are inconsistent with its findings concerning the lack of written description support. The Federal Circuit found no such inconsistency, noting that Persion’s entire argument with respect to this issue is based on incomplete quotations from the district court’s opinion.

In Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Trend Micro Inc., [2019-1122] (December 19, 2019), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded a finding of excptionality under 35 USC 285, because it was unclear whether the

district court applied the proper legal standard.

During cross-examination at trial, Intellectual Ventures’s expert

changed his opinion about the meaning of the term “characteristic.” Following the completion of trial in the Symantec action, Trend Micro moved for clarification of the district court’s claim constructions in light of the expert’s changed opinion. During the hearing on Trend Micro’s motion, Intellectual Ventures’s counsel maintained that the expert had not changed his opinion, despite the expert’s clear trial testimony to the contrary. The

district court granted Trend Micro’s motion for clarification. The district court also granted leave for Symantec and Trend Micro to file motions

for judgment as a matter of law that the asserted patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Trend Micro moved for attorney fees under § 285, requesting that the court declare the case exceptional due to the circumstances surrounding Intellectual Ventures’s expert’s changed opinion. The district court granted Trend Micro’s motion, concluding that Intellectual Ventures’s conduct was exceptional solely with respect to this collection of circumstances regarding its expert’s changed testimony, and awarded $444,051.14 in attorneys’ fees. . However, the Federal Circuit found that the case overall was not exceptional, concluding that it would be wrong to say that Intellectual Ventures’s case was objectively unreasonable.

Section 285 provides that “[t]he court in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party.” 35 U.S.C. § 285. An exceptional case “stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of a party’s litigating position (considering both the governing law and the facts of the case) or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated. District courts may determine whether a case is ‘exceptional’

in the case-by-case exercise of their discretion, considering the totality of the circumstances.

Applying an abuse of discretion standard, the Federal Circuit said it was not clear that the district court applied the proper legal standard when it considered whether the case was exceptional under §285. The Federal Circuit said that instead of determining whether the case was exceptional,

it appears that the district court may have focused on whether one discrete portion of the case stood out from other cases, from all the other portions of this case, in terms of either the substantive strength of a position was advocating or the manner with which Intellectual Ventures was litigating.

The Federal Circuit said that Section 285 gives the district court discretion to depart from the American Rule and award attorney fees “in exceptional cases.” Accordingly, under the statute, the district court in this case should

have determined whether the circumstances surrounding the expert’s changed opinion were such that, when considered as part of the totality of circumstances in the case, the case stands out as exceptional.

The Federal Circuit rejected Intellectual Venture’s argument that a case cannot be found exceptional based on a single, isolated act, holding that a district court has discretion, in an appropriate case, to find a case exceptional based on a single, isolated act. Whether the conduct is a single, isolated act or otherwise, the relevant question for the district court is the same. The district court must determine whether the conduct, isolated or otherwise, is such that when considered as part of and along with the totality of circumstances, the case is exceptional, i.e., the case stands out among others with respect to the substantive strength of a party’s litigating position or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated. However in all cases there must be a finding of an exceptional case—not a finding of an exceptional portion of a case—to support an award of

partial fees.

In Fox Factory , Inc. v. SRAM, LLC, [2018-2024, 2018-2025] (December 18, 2019), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded that the district court’s determination that claims 1–6 and 13–19 of U.S. Patent No. 9,182,027 was not obvious based on its analysis of secondary considerations. The independent claims of the ’027 patent—claims 1, 7, 13, and 20—recite a bicycle chainring with alternating narrow and wide tooth tips and teeth offset from the center of the chainring.

The Board determined that SRAM was entitled to a presumption of nexus between the challenged outboard offset claims and secondary considerations evidence pertaining to SRAM’s X-Sync products, subject to two limitations. First, the Board stated that evidence of secondary considerations “specifically directed” to either an inboard or outboard offset X-Sync product is only entitled to a presumption of nexus with the claims reciting the same type of offset. Second, the Board explained that the presumption of nexus only applies when a product is “coextensive” with a patent claim.

On appeal, FOX contended that the Board applied the wrong standard for determining whether SRAM was entitled to a presumption of nexus between the challenged claims and SRAM’s evidence of secondary considerations, and the Federal Circuit agreed.

In order to accord substantial weight to secondary considerations in an obviousness analysis, the evidence of secondary considerations must have a “nexus” to the claims, i.e., there must be a legally and factually sufficient connection’ between the evidence and the patented invention. The Federal Circuit noted that the patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists. To determine whether the patentee has met that burden, the consideration is the correspondence between the objective evidence and the claim scope.

A patentee is entitled to a rebuttable presumption of nexus between the asserted evidence of secondary considerations and a patent claim if the patentee shows that the asserted evidence is tied to a specific product and that the product is the invention disclosed and claimed. Conversely, when the thing that is commercially successful is not coextensive with the patented invention—for example, if the patented invention is only a component of a commercially successful machine or process, the patentee is not entitled to a presumption of nexus.

The existence of one or more unclaimed features, standing alone, does not mean that nexus may not be presumed. There is rarely a perfect correspondence between the claimed invention and the product. The purpose of the coextensiveness requirement is to ensure that nexus is only presumed when the product tied to the evidence of secondary considerations is the invention disclosed and claimed. If the unclaimed features amount to nothing more than additional insignificant features, presuming nexus may nevertheless be appropriate.

The Federal Circuit explained that the degree of correspondence between a product and a patent claim falls along a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum lies perfect or near perfect correspondence. At the other end lies no or very little correspondence, such as where the patented invention is only a component of a commercially successful machine or process.

In the instant case the Federal Circuit concluded that no reasonable fact finder could conclude, under the proper standard, that the X-Sync chainrings are coextensive with the ‘027 patent claims. The Federal Circuit noted that the chainrings include unclaimed features that the patentee describes as “critical” to the product’s ability to “better retain the chain under many conditions” and that go to the “heart” of another one of Patent Owner’s patents. The Federal Circuit said that In light of the patentee’s own assertions about the significance of the unclaimed features, no reasonable fact finder could conclude that these features are insignificant.

Because it could not say that the X-Sync chainrings are the invention claimed by the independent claims, the Board erred in presuming nexus between the independent claims of the ’027 patent and secondary considerations evidence pertaining to the X-Sync chainrings. Because the Board erroneously presumed nexus between the evidence of secondary considerations and the independent claims, the Federal Circuit vacated the Board’s non-obviousness determination and remanded for further proceedings. On remand, the Federal Circuit said that the Patent Owner will have the opportunity to prove the nexus between the challenged independent claims and the evidence of secondary considerations.

In Syngenta Crop Protection, LLC v. Willowood, LLC, [2018-1614, 2018-2044](December 18, 2019) affirmed-in-part, reversed-in-part, vacated-in-part, and remanded the district court’s judgment in favor of all defendants on infringement of one patent at issue; and against Willowood, LLC, and Willowood USA, LLC, on infringement of the remaining three patents.

The Federal Circuit remanded the dismissal of Syngenta’s copyright claim for a more detailed determination whether FIFRA required defendants to copy the copied portions of Syngenta’s labels.

In a case of first impression reversed the district court’s requirement that that all steps of a patented process be performed by or at the direction or control of a single entity before infringement liability under 35 USC 271(g) can attach.

Section 271(g) provides that “[w]hoever without authority imports into the United States or offers to sell, sells, or uses within the United States a product which is made by a process patented in the United States shall be liable as an infringer.” The Federal Circuit said that this language makes clear that the acts that give rise to liability under § 271(g) are the importation, offer for sale, sale, or use within this country of a product that was made by a process patented in the United States. The Federal Circuit said that nothing in the statutory language suggests that liability arises from practicing the patented process abroad. Rather, the focus is only on acts with respect to products resulting from the patented process. The Federal Circuit concluded that because the statutory language as a whole is clear that practicing a patented process abroad cannot create liability under § 271(g), whether that process is practiced by a single entity is immaterial to the infringement analysis under that section.

The Federal Circuit otherwise affirmed the infringement determinations.

In Chamberlain Group, Inc. v. One World Technologies, Inc., [2018-2112](December 17, 2019), the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision that claims 18-25 of U.S. Patent No. 7,196,611 were anticipated.

Claims 18–25 of the ’611 patent are directed to an “interactive learn mode” that guides a user through installation and learn mode actions. One World challenged the patent based on a prior Chamberlain patent that allows the user to program the upper and lower limits for the garage door’s movement. Chamberlain tried to distinguish its earlier patent, arguing that the prior patent taught setting limits in sequence, rather than at the same time. The Board rejected this argument finding that nothing in the claims of the ‘611 patent required setting limits at the same time.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that nothing in the claims requires the activities to be identified together or at the same time. The Federal Circuit noted that Chamberlain’s own expert testified that claims were “silent on any timing requirement.” Given the absence of any timing limitation, the Board reasonably found that the prior patents disclosure of transmitting the signals in sequence, one after the other in response to the previously-completed steps of identifying the garage door operator’s present status and activities to be completed taught the “responsive to” step. Thus, the Federal Circuit held that Board’s finding that Schindler anticipates claims of the ’611 patent is supported by substantial evidence, and affirmed.

In Blackbird Tech LLC v. Health in Motion LLC, [2018-2393] (December 16, 2019), the Federal Circuit affirmed the award of $363,243.80 attorney fees and expenses when Blackbird after nineteen months of litigation, voluntarily dismissed its suit with prejudice and executed a covenant not to sue.

An exceptional case is simply one that stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of a party’s litigating position (considering both the governing law and the facts of the case) or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated. There is no precise rule or formula for making these determinations; instead, district courts may determine whether a case is exceptional in the case-by-case exercise of their discretion, considering the totality of the circumstances.

Considering the totality of the circumstances, the District Court found that Blackbird’s case against Appellees is exceptional within the meaning of §285 because it stands out from others with respect to both the substantive strength of Blackbird’s litigation position and the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated by Blackbird.

The Federal Circuit noted that the District Court found that Blackbird’s litigation position was “meritless” and “frivolous, determining that when challenged on the merits, Blackbird raised flawed claim construction and infringement contentions, and ultimately did not prevail on the merits because Blackbird dismissed its claims with prejudice, and submitted a covenant not to sue on the eve of trial. The Federal Circuit noted that even accepting Blackbird’s proposed construction, the accused device does not include a housing that meets the requirements of independent claim 1.

The Federal Circuit rejected Blackbird’s argument that the district court merely found its position “flawed” and not objectively baseless. The Federal Circuit also rejected Blackbird’s argument that neither Health in Motion nor the district court gave adequate notice of the purported weakness of its position. The Federal Circuit said that the district court was not obliged to advise Blackbird of the weaknesses in its litigation position, and further that the exercise of even a modicum of due diligence by Blackbird, as part of a pre-suit investigation, would have revealed the weaknesses in its litigation position.

The Federal Circuit also agreed that the case stands out with respect to the manner in which Blackbird litigated. The district court found that the case was exceptional because Blackbird litigated in an unreasonable manner. including making nuisance value settlement offers, unreasonable delays in producing documents, and finally, filing a notice of dismissal, covenant not to sue, and motion to dismiss without first notifying Health in Motion’s counsel, on the same day pretrial submissions were due and shortly before its motion for summary judgment was to be decided. The Federal Circuit further found that the district court did not abuse its discretion by considering the need to deter future abusive litigation, noting that Blackbird has filed over one hundred patent infringement lawsuits, and none have been decided, on the merits, in favor of Blackbird.

Finally, the Federal Circuit rejected Blackbird’s complaint about the amount of the award. Specifically the Federal Circuit rejected the argument that defendants should not have spent so much on the defense of such a small claim. The Federal Circuit added that the record supports the conclusion that Blackbird’s misconduct so severely affected every stage of the litigation that a full award of attorney fees was proper.

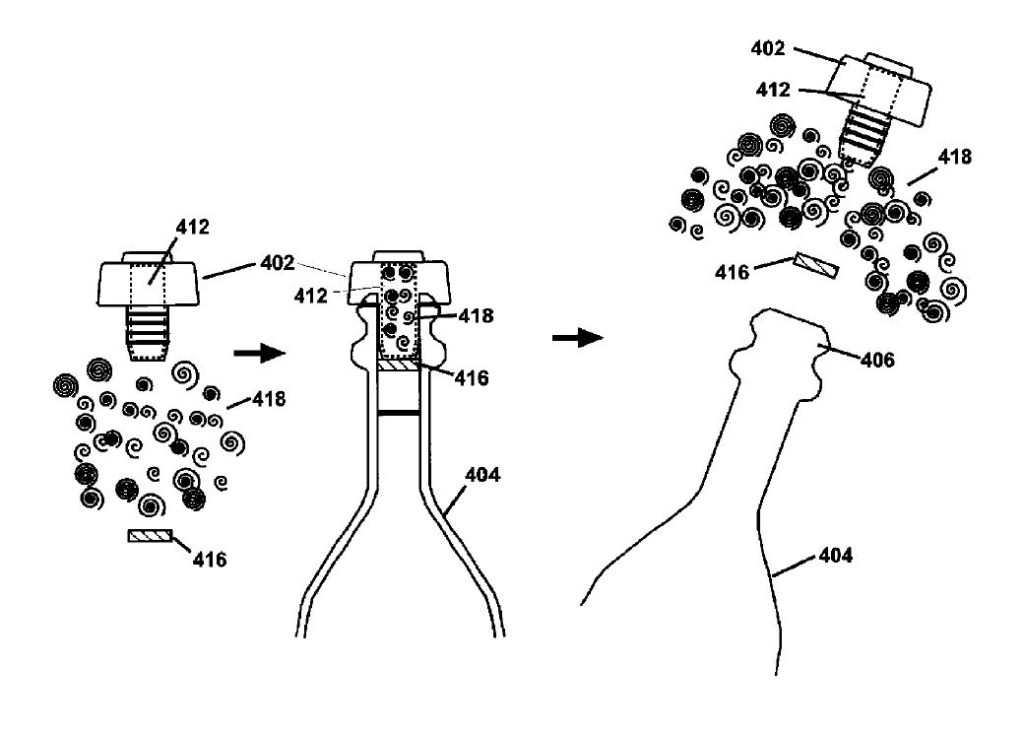

In Amgen Inc. v. Hospira, Inc., [2019-1067, 2019-1102](December 16, 2019), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s determination that Amgen’s U.S. Patent No. 5,856,298 was infringed and not invalid; fourteen batches of Hospira’s erythropoietin biosimilar drug product were not covered by the Safe Harbor provision of 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1); Amgen had proven it was entitled to $70 million in damages; denying Amgen motion for judgment as a matter of law that Amgen’s U.S. Patent No. 5,756,349 was infringed.

After substantial evidence supporting the validity and infringement of the ‘298 patent, the Federal Circuit turned to the safe harbor provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1). The instruction to the jury said that “If Hospira has proved that the manufacture of a particular batch was reasonably related to developing and submitting information to the FDA in order to obtain FDA approval, Hospira’s additional underlying purposes for the manufacture and use of that batch do not remove that batch from the Safe Harbor defense.” Hospira complained that this improperly focused on Hospira’s intent for manufacturing batches of EPO.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that the jury instructions properly articulated the legal principles underlying the Safe Harbor inquiry. Section 271(e)(1)’s exemption from infringement extends to all uses of patented inventions that are reasonably related to the development and submission of any information under the FDCA. The Federal Circuit said that relevant inquiry, therefore, is not how Hospira used each batch it manufactured, but whether each act of manufacture was for uses reasonably related to submitting information to the FDA.2 The jury instructions properly asked whether each act of manufacture, that is, each accused activity, was for uses reasonably related to submitting information to the FDA. The Federal Circuit added that contrary to Hospira’s contentions, the instructions struck the appropriate balance by telling the jury that Hospira’s additional underlying purposes do not matter as long as Hospira proved that the manufacture of any given batch of drug substance was reasonably related to developing information for FDA submission.

Hospira argued that no reasonable jury could find that some of the batches it made were protected by the safe harbor, while some were not. However the Federal Circuit found that substantial evidence supported the jury’s finding that the batches at issue were not manufactured “solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information” to the FDA. There was testimony that Hospira was not required to manufacture additional batches after it made its initial batches. There was also testimony that stability testing was not required but would be part of a “continuing program for stability that is a postapproval commitment.

On the issue of damages, Hospira argued that its Daubert motion to disqualify Amgen’s damages expert should have been granted. However, the Federal Circuit found no reversible error, noting that the district court permitted Hospira to cross-examine Amgen’s expert and to present the testimony of its own damages expert, and make the very arguments it was now raising on appeal. The Federal Circuit said it was not unreasonable for the jury to choose a damages award within the amounts proposed by each expert, and affirm the district court’s denial of Hospira’s JMOL motion.

Lastly, the Federal Circuit agreed that the finding of non infringement of ‘349 patent was supported by substantial evidence.

In Peter v. Nantkwest, Inc., — US — (2019), the Supreme Court, citing the bedrock principle known as the “American Rule” that each litigant pays his own attorney’s fees, win or lose, unless a statute or contract provides otherwise, held that the PTO could not recoup its attorneys fees under §145 from an applicant who challenges a final rejection in district court.

The decision is a relief to all applicants, because it leaves a civil action as a viable remedy to an improper final rejection. But it still leaves applicants liable for the PTO’s “expenses of the proceedings,” win or lose. It is a little galling to have to pay the PTO’s “expenses” in unsuccessfully defending an improper rejection, but that is an issue to take up with Congress, not the courts.

Resort to the courts when one believes that the government has screwed up is an important remedy that keeps the system in balance. The Supreme Court’s decision maintains that balance, preserving the availability of court challenges of incorrect decisions by the examining corps.