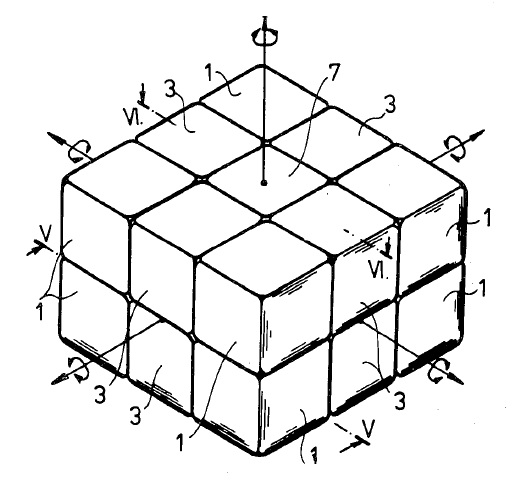

On March 29, 1983, U.S. Patent No. 4,378,116 issued to Erno Rubik on a Spatial Logical Toy, the Rubik’s Cube

March 28 Patent of the Day

March 27 Patent of the Day

March 26 Patent of the Day

On March 26, 1845, U.S. Patent No. 3,965 issued to William Sheout and, Horace Day on an Improvement in Adhesive Plaster — a precursor to band-aids.

March 25 Patent of the Day

March 24 Patent of the Day

Estoppel Does Not Apply to Uninstituted Grounds in an IPR

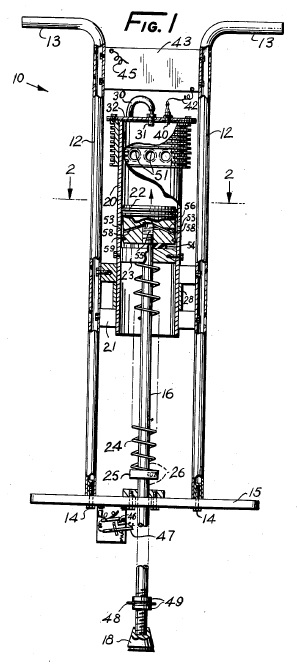

In Shaw Industries Group, Inc. v. Automated Creel Systems, Inc., [2015-1116, -1119] (March 23, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed in part, vacated-in-part, and remanded the USPTO’s final written decision regarding claims 1-21 of U.S. Patent No. 7,806,360 relating to “creels” for supplying yarn and other stranded materials to a manufacturing process.

Shaw challenged the Board’s institution decision that refused to consider one of the proffered grounds of unpatentability as redundant. The Federal Circuit noted that the Board did not consider the substance of the cited reference, or compare it to the other cited art, nor did the Board make specific findings that the grounds overlapped or even involved overlapping arguments. Instead the Board merely denied the ground as redundant. While pointing out that it may not agree with the Board’s handling of the Petition, or that the Board’s handling was more efficient, the Federal Circuit said it had no authority to review the Board’s decision not to institute. Shaw persisted and requested a writ of mandamus, but the Federal Circuit found that Shaw had not shown it was entitled this extraordinary remedy, rejecting the Shaw’s argument that it had no other adequate means to attain the desired relief, because it would be estopped to raise the redundant grounds that the Board refused to hear.

The Federal Circuit held that §315(e) would not estop Shaw from re-raising the redundant grounds in either the PTO or the district courts. The Federal Circuit said that both parts of § 315(e) create estoppel for arguments “on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.” Shaw raised the redundant ground in its petition for IPR, but the PTO denied the petition as to that ground, thus no IPR was instituted on that ground, and the IPR does not begin until it is instituted.

This language does not appear to be limited to grounds that are not instituted for redundancy, and thus would also apply to grounds that the Board finds did not meet the or the “likelihood of success” and the more rigorous “more likely than not” standards of IPR and PGR proceedings.

It is conceivable that the Federal Circuit could later distinguish between grounds rejected on their merits and grounds merely found redundant, but their holding that there is no estoppel on grounds that are not instituted appears straight-forward and unambiguous. Thus a petitioner may be able to preserve grounds by mentioning them, but not adequately supporting them, the resulting denial of institution protecting the petitioner from any estoppel effects.

Finally, the Federal Circuit held that it lacked authority to review the Board’s decision that the petition was not barred pursuant to 35 U.S.C. §315(b). Leaving the Board’s curious rule that a complaint served but later dismissed does not count as a complaint, completely unreviewable.

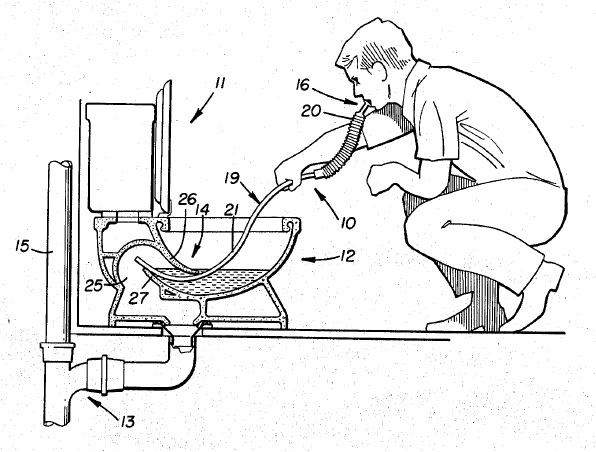

March 23 Patent of the Day

Assignor Estoppel is Still A Thing

In Mag Aerospace Industries, Inc. v, B/E Aerospace, Inc., [2015-1370, 1426] (March 23, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment of non-infringement, and the district court’s ruling that the doctrine of assignor estoppel barred B/E from challenging the validity of the patents.

One of the inventors of the patents-in-suit, Pondelick, now works for B/E..but Pondelick assigned the patents to his former employer, who in turn assigned them to MAG. The district court concluded that Pondelick was in privity with B/E and thus that assignor estoppel applied to bar B/E from attacking the validity of the patents.

The district court analyzed a number of factors identified in Shamrock Technologies to determine whether a finding of privity was appropriate:

- the assignor’s leadership role at the new employer;

- the assignor’s ownership stake in the defendant company;

- whether the defendant company changed course from manufacturing non-infringing goods to infringing activity after the inventor was hired;

- the assignor’s role in the infringing activities;

- whether the inventor was hired to start the infringing operations;

- whether the decision to manufacture the infringing product was made partly by the inventor;

- whether the defendant company began manufacturing the accused product shortly after hiring the assignor; and

- whether the inventor was in charge of the infringing operation.

The district court acknowledged B/E’s arguments but found on balance that assignor estoppel was appropriate. The Federal Circuit found that the district court’s conclusion was not clearly erroneous, agreeing that many of the Shamrock factors weigh in favor of finding privity.

Of course the PTAB does not apply Assignor Estoppel, so patent challengers should raise their challenges there, and patent assignees should consider language in their assignments to forestall such challenges.