The technology documented by the U.S. patent collection has information relevant to every human endeavor, and Valentine’s Day is no exception. Consider the following patents on solutions to the vexing problems presented by Valentine’s Day:

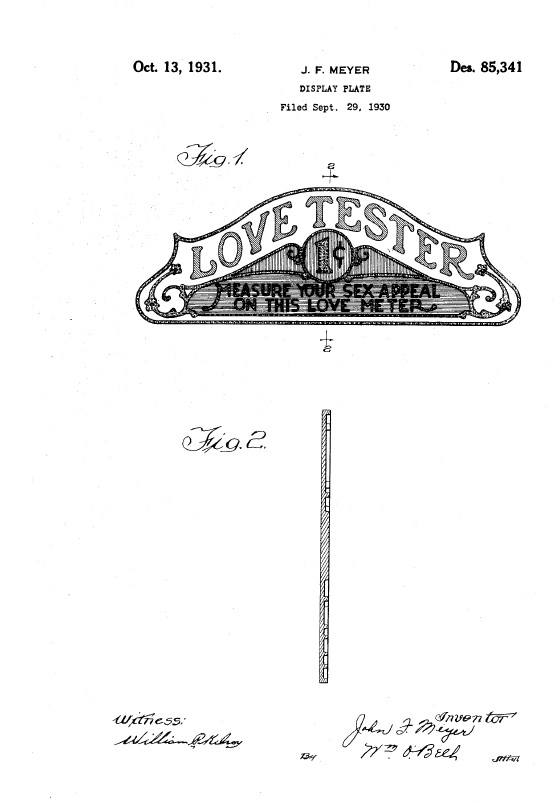

U.S. Patent No. D85,341 protects a Love Tester.

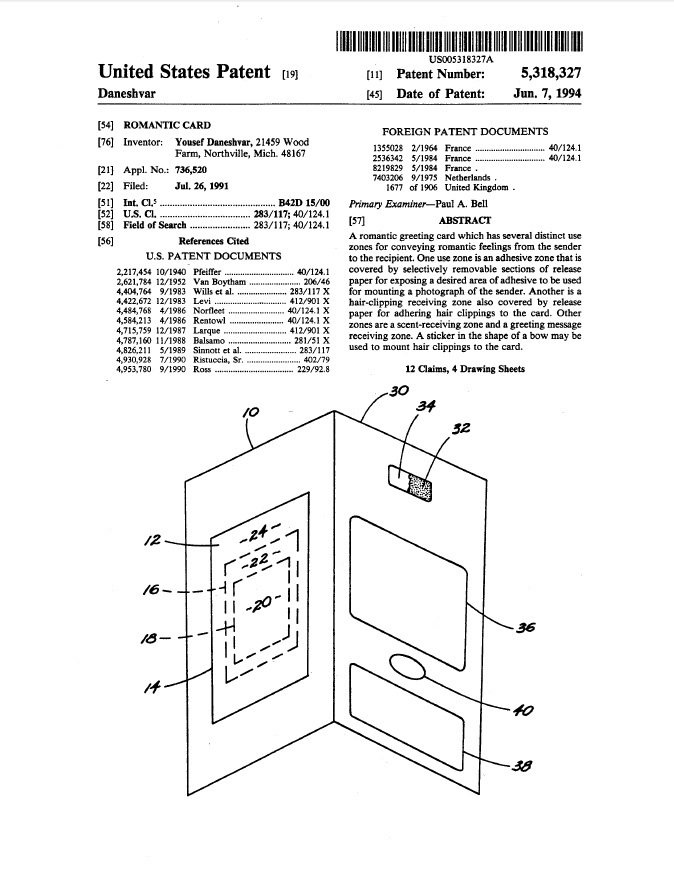

U.S. Patent No. 5,318,327, protected a Romantic Card

U.S. Patent No. 5,318,327, protected a Romantic Card

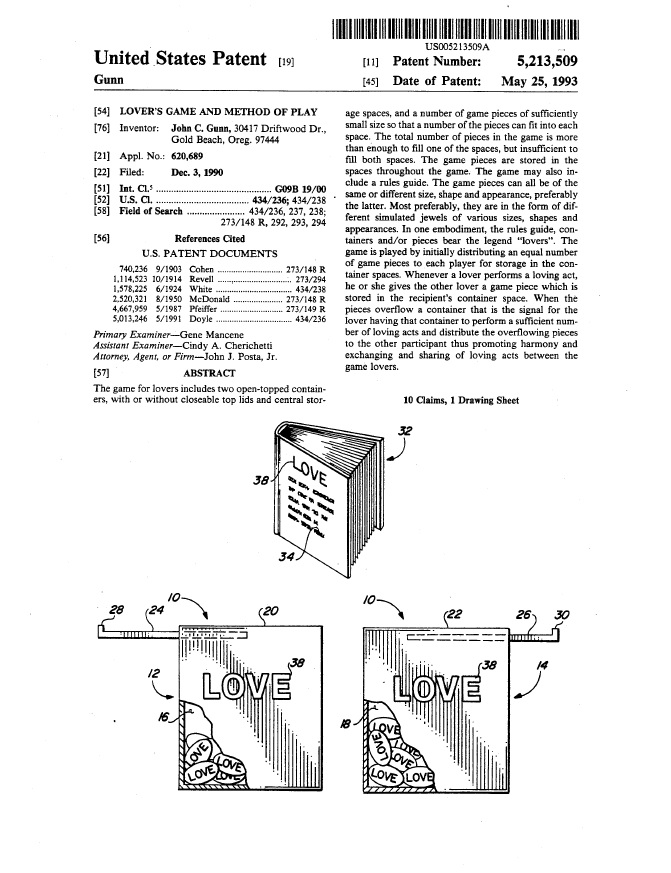

U.S. Patent No. 5,213,509 Protected a Lover’s Game and Method of Play

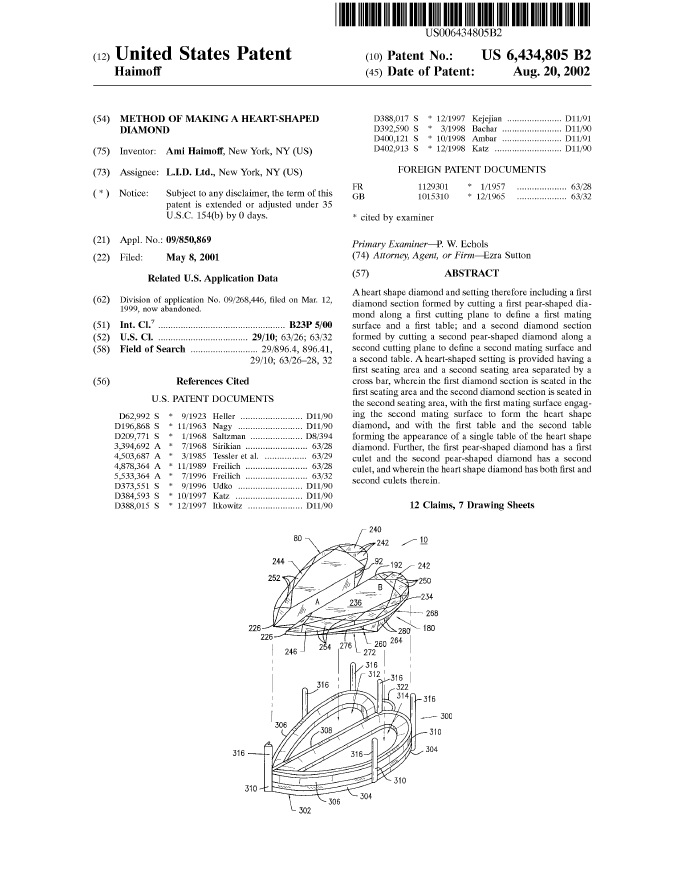

U.S. Patent No. 6,434,805 protects a Method of Making a Heart-Shaped Diamond

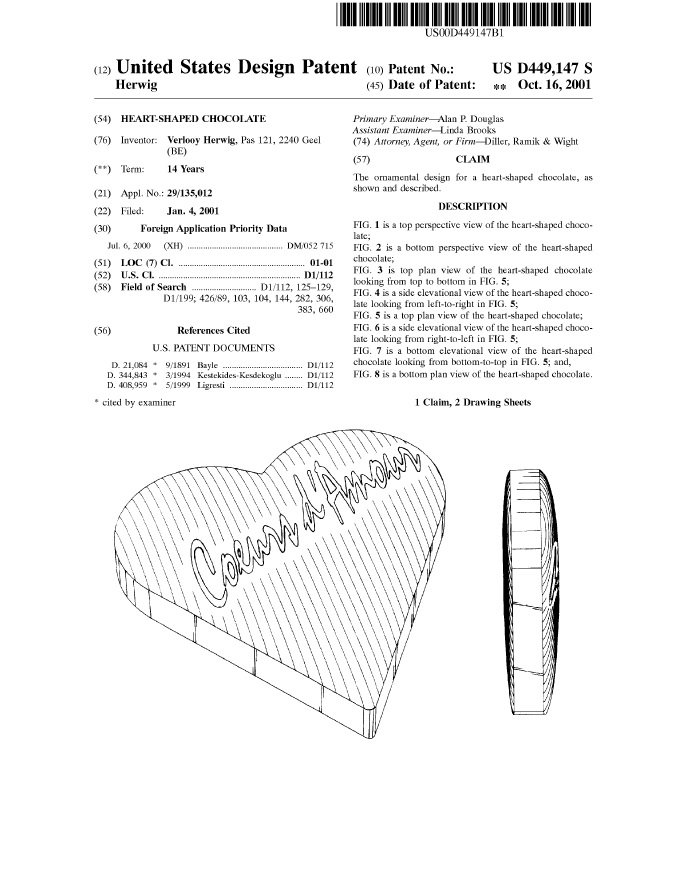

U.S. Patent No. D449,147 Protected a Heart-Shaped Chocolate

U.S. Patent No. D449,147 Protected a Heart-Shaped Chocolate

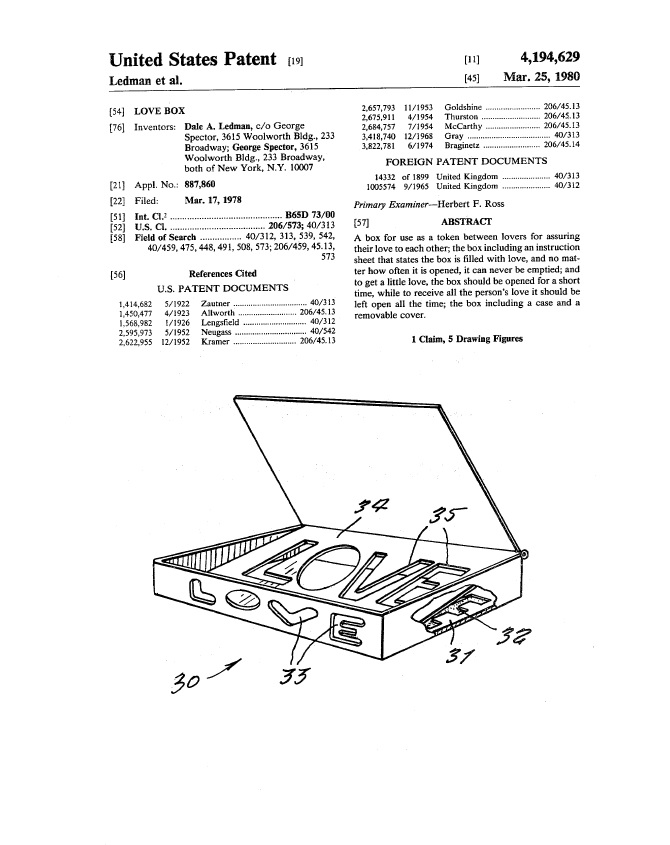

U.S. Patent No. 4,194,629 Protected a Love Box

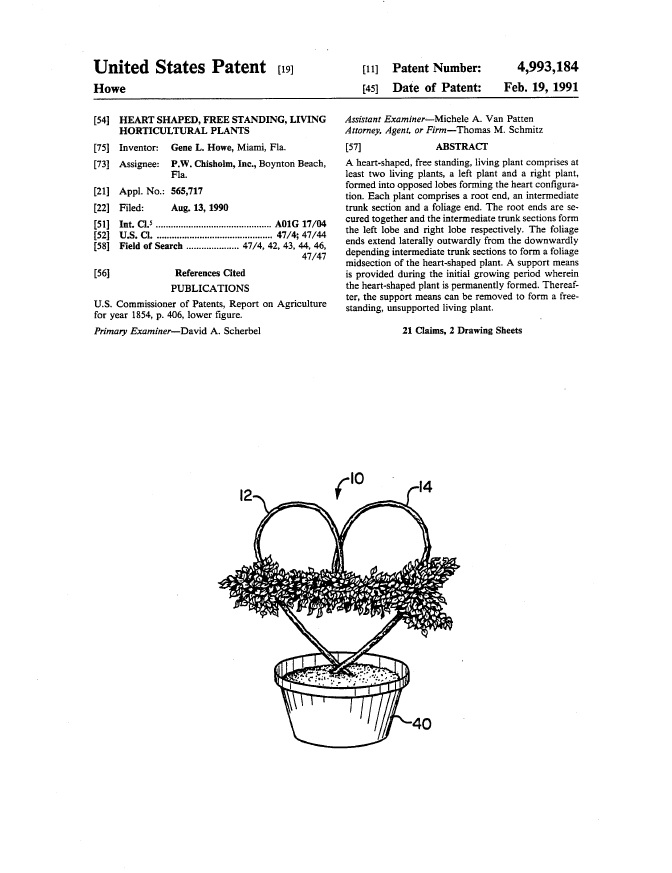

U.S. Patent No. 4,993,184 Protected a Heart-Shaped, Free-Standing, Living Horticultural Plants

U.S. Patent No. 4,993,184 Protected a Heart-Shaped, Free-Standing, Living Horticultural Plants

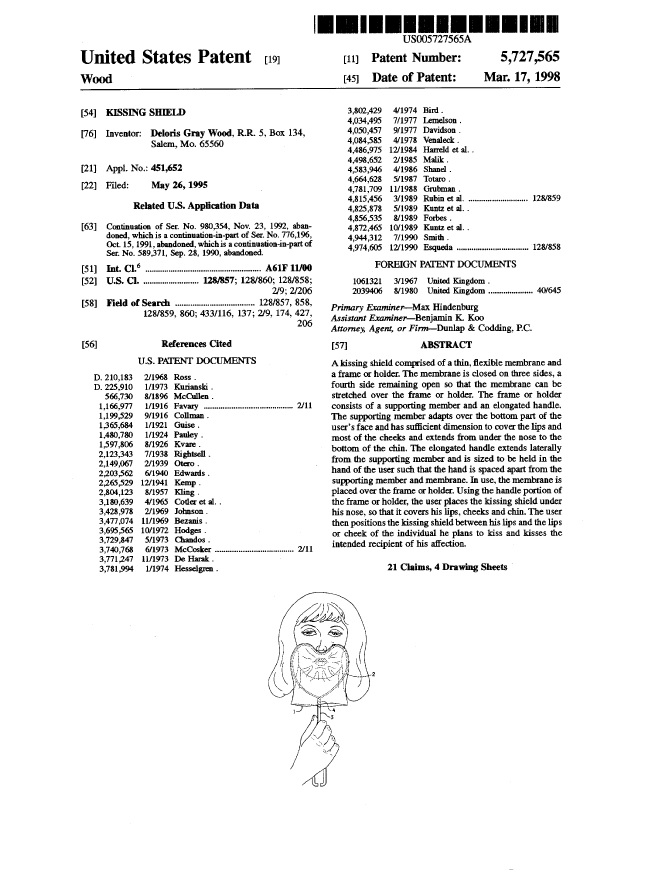

U.S. Patent No. 5,727,565 Protects a Kissing Shield

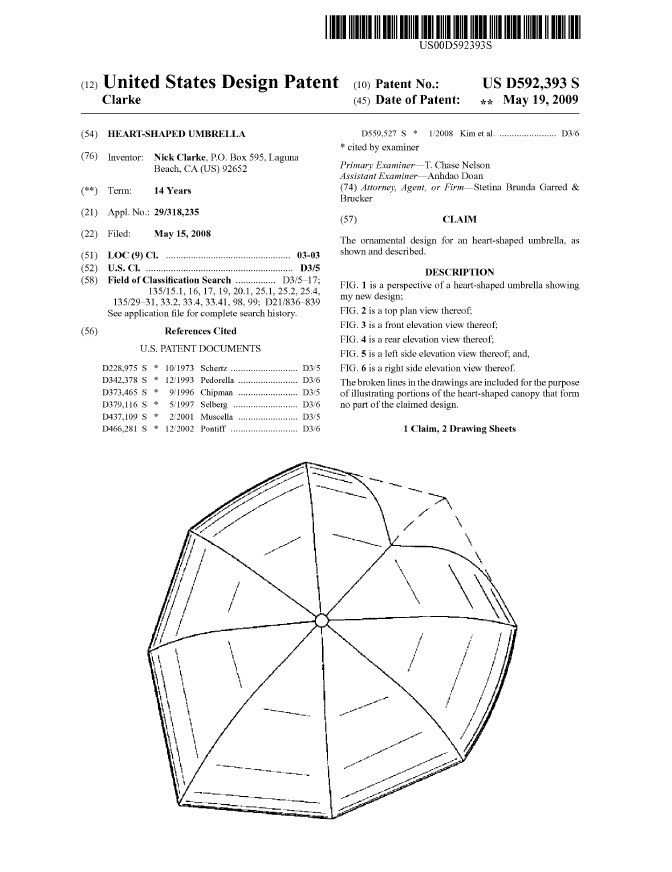

U.S. Patent No. D592,393 Protects a Heart-Shaped Umbrella

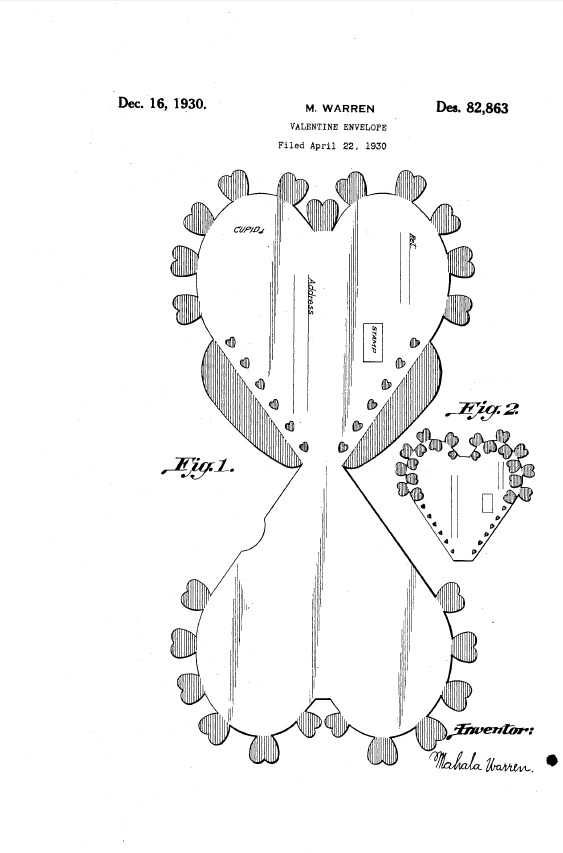

U.S. Patent No. D82,863 Protects a Valentine Envelope

U.S. Patent No. D82,863 Protects a Valentine Envelope

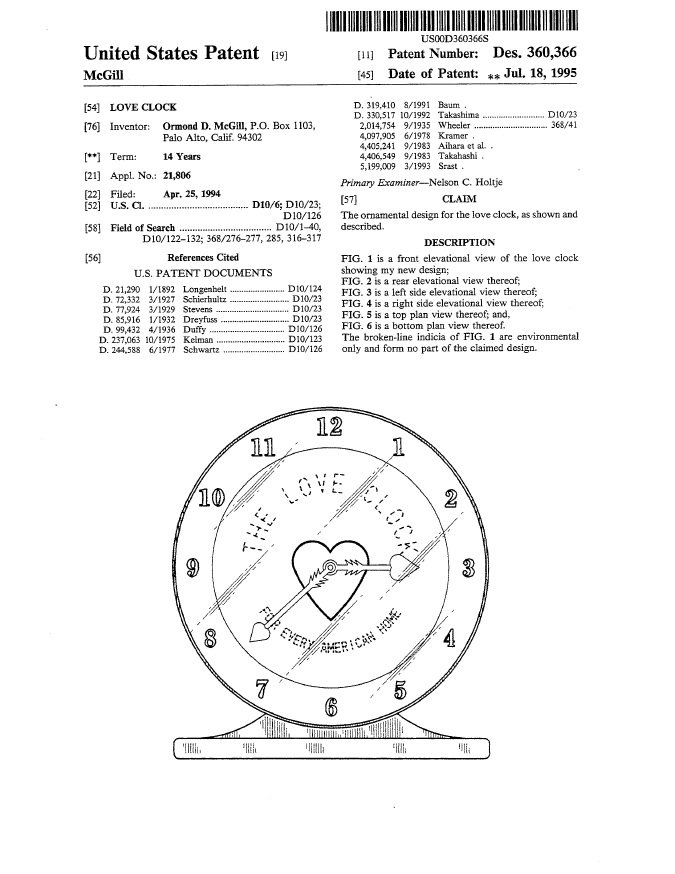

U.S. Patent No. D360,366 Protects a Love Clock

U.S. Patent No. D360,366 Protects a Love Clock

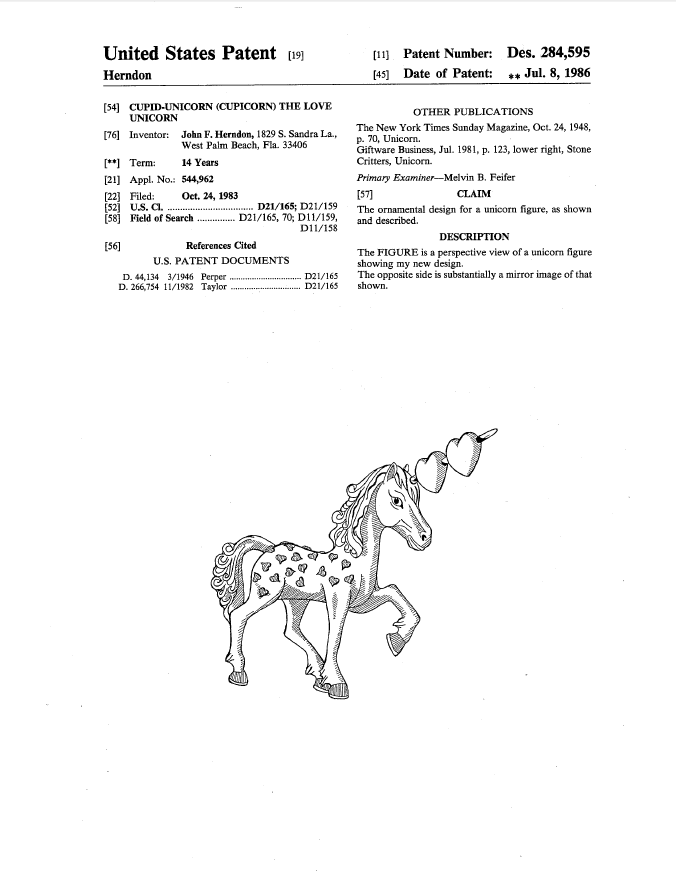

U.S. Patent No. D284,595 Protected Cupid Unicorn (Cupicor) the Love Unicorn

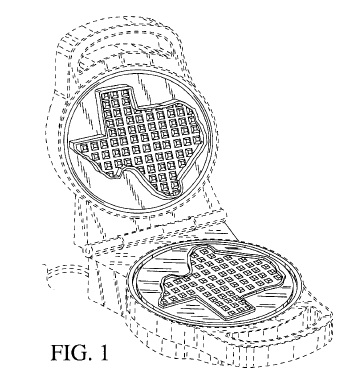

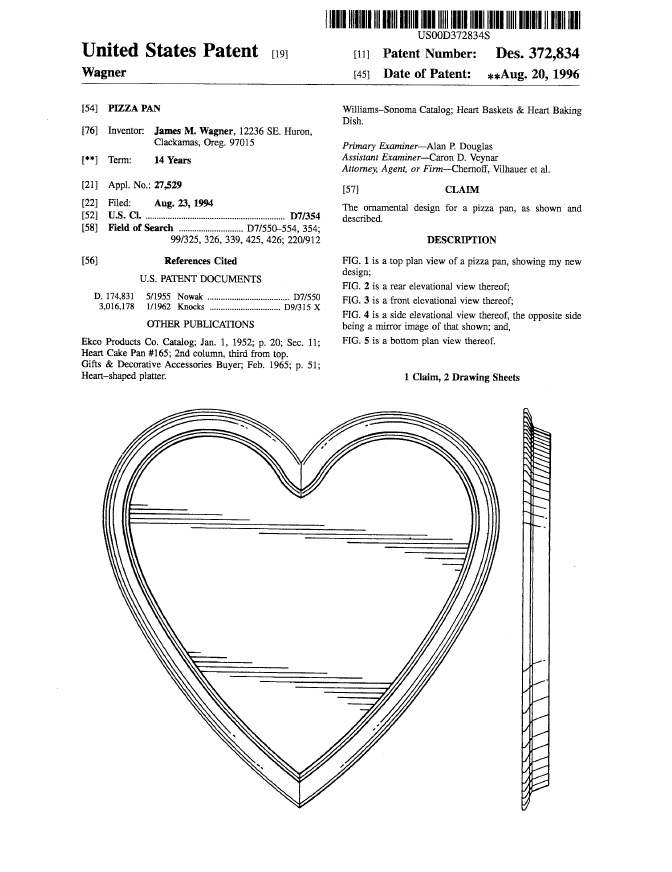

U.S. Patent No. 372,594 protects a Pizza Pan

U.S. Patent No. 372,594 protects a Pizza Pan

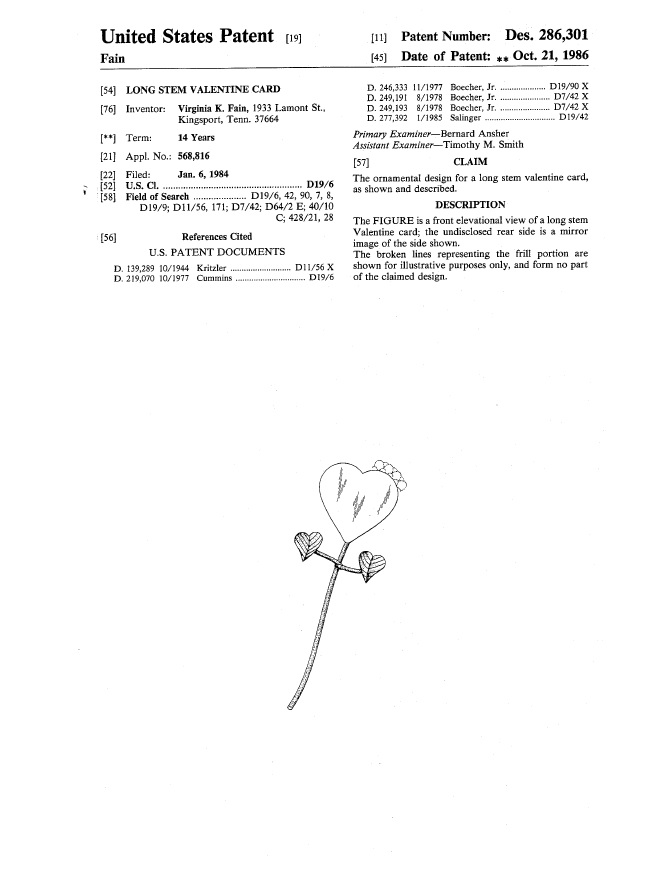

U.S. Patent No. 286,301 Protects a Long Stem Valentine Card

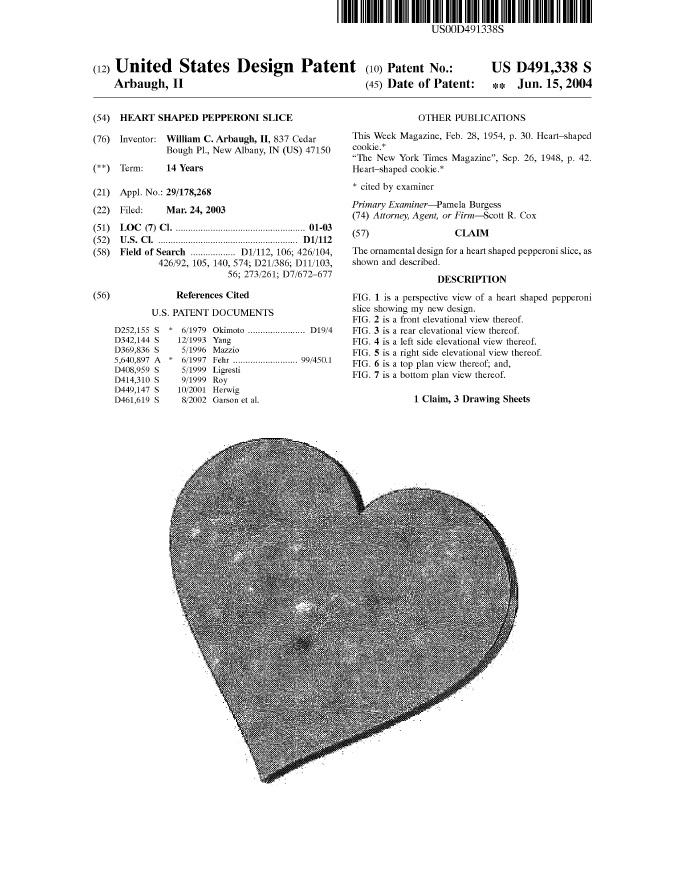

U.S. Patent No. D491,338 Protects Heart-Shaped Pepperoni Slices

U.S. Patent No. D491,338 Protects Heart-Shaped Pepperoni Slices