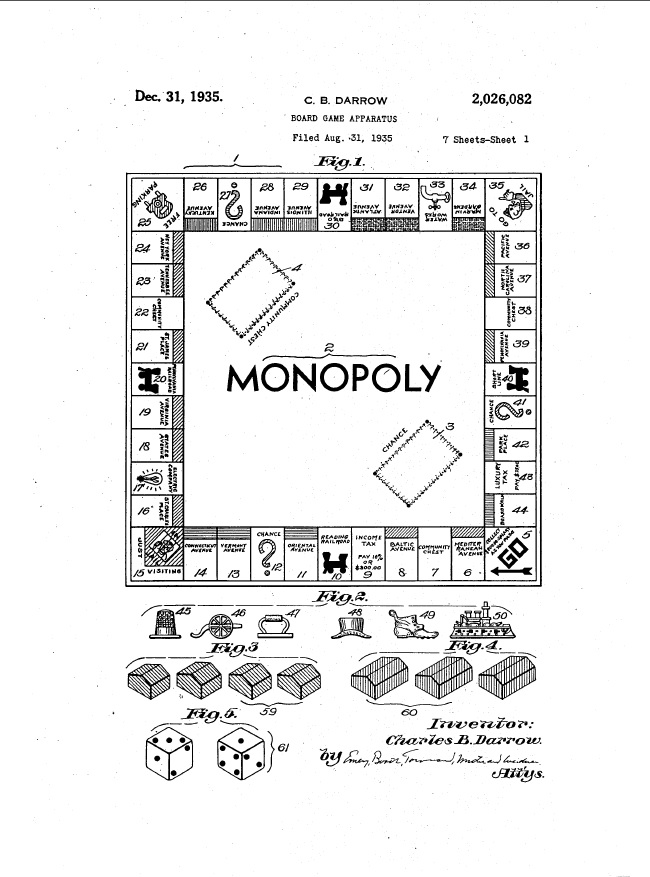

On December 31, 1935, Charles B. Darrow obtained U.S. Patent No. 2,026,082 on Board Game Apparatus, protecting the game Monopoly. Happy New Year!

Happy New Year!

A Patent on Games? No Dice.

In In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., [2017-2465](December 28, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the PTAB affirming the rejection of claims 1–3, 5, 7–14, 16–18, and 23–30 of U.S. Patent Application No. 13/078,196 under 35 U.S.C. § 101 for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter.

The application, entitled “Casino Game and a Set of Six-Face Cubic Colored Dice,” relates to dice games intended to be played in gambling casinos, in

which a participant attempts to achieve a particular winning combination of subsets of the dice.

The Examiner concluded that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “rules for playing a game,” which fell within the realm of “methods of organizing human activities.” The examiner also

concluded that the claims were unpatentable for obviousness over U.S. Patent No. 4,247,114 over matters old and well known to dice games, applying the printed matter doctrine. The Board affirmed both rejections.

The Federal Circuit found its decision in In re Smith, 815 F.3d 816 (Fed. Cir. 2016), where it found a method of conducting a wagering game using a

deck of playing cards was drawn to an abstract idea, to be “highly instructive.” In the present case, as in In re Smith, the claims were directed to a method of conducting a wagering game, but using dice instead of cards. with the probabilities based on dice rather than on cards.

The Federal Circuit agreed with Applicant/Appellant that the USPTO’s category of unpatentable subject matter “methods of organizing human activities” can be confusing and potentially misused, but where the decision further articulates a more refined characterization of the abstract idea (e.g., “rules for playing games”), there was no error in also observing that the claimed abstract idea is one type of method of organizing human activity.

The Federal Circuit said that abstract ideas, including a set of rules for a game, may be patent-eligible if the claims contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible application. On appeal, Applicant/Appellant contended that the specifically-claimed dice that have markings on one, two, or three die faces are not conventional and their recitation in the claims amounts to “significantly more” than the abstract idea. The Federal Circuit said that the markings on Appellant’s dice constituted printed matter, as pointed out by the Board, and this court has generally found printed matter to fall outside the scope of §101.

Specifically, the Federal Circuit said that each die’s marking or lack of marking communicates information to participants indicating whether the

player has won or lost a wager, similar to the markings on a typical die or a deck of cards. Accordingly, the recited claim limitations are directed to information. Additionally, the Federal Circuit observed that the printed indicia on each die are not functionally related to the substrate of the dice.

The Federal Circuit also rejected rejected applicant’s argument that the claimed method of playing a dice game cannot be an abstract idea because it recites a physical game with physical steps. The Federal Circuit said that the abstract idea exception does not turn solely on whether the claimed invention comprises physical versus mental steps.

The Federal Circuit concluded that because the only arguably unconventional aspect of the recited method of playing a dice game is printed matter, which falls outside the scope of § 101, the rejected

claims did not recite an “inventive concept” sufficient to “transform” the claimed subject matter into a patent eligible application of the abstract idea.

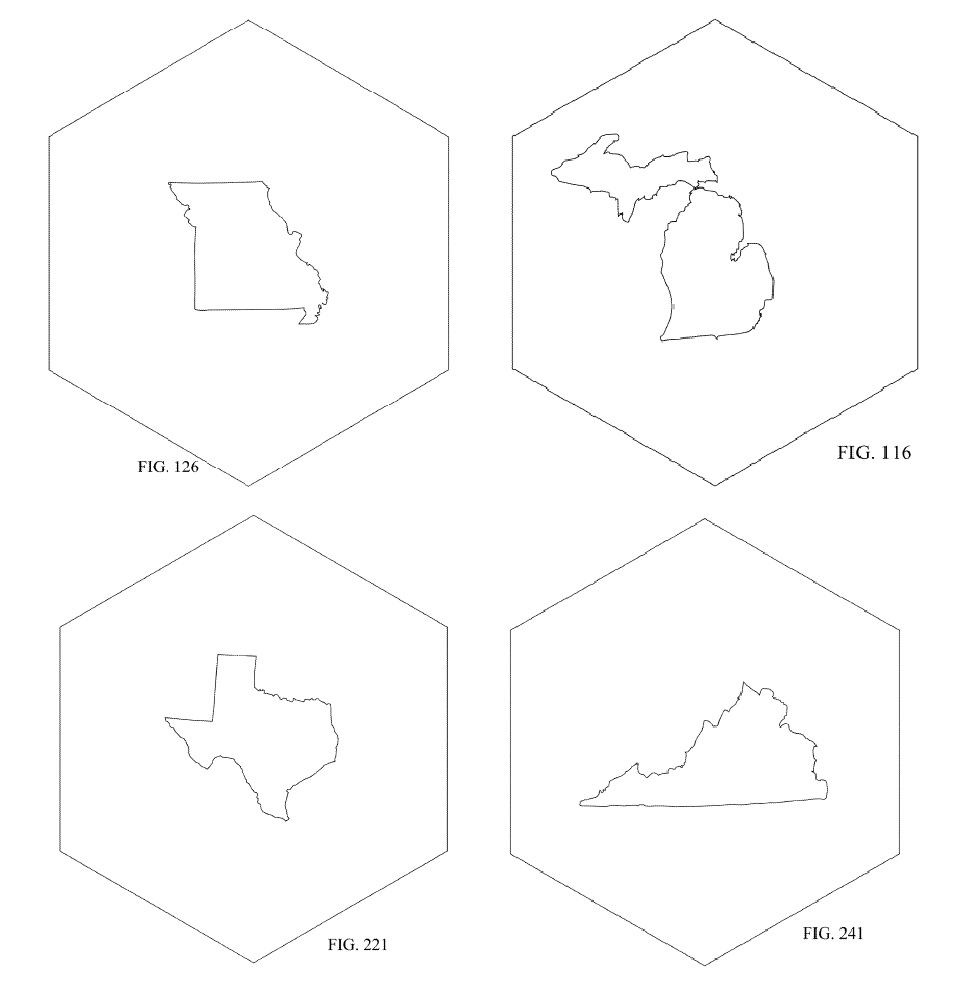

The “State” of Embodiments in Design Patents

U.S. Patent No. D824219 issued on July 31, 2018 on a “Coaster State Bottle Opener.” This patent is interesting because it has 52 embodiments that are depicted in 260 Figures, featuring every state on its own coaster/bottle opener.

allow you to assemble a lovely coast collection featuring Harness, Dickey locations!

Applicants are of course entitled to present as many embodiments as they wish in a design patent application. MPEP 1504.05 states that “[m]ore than one embodiment of a design may be protected by a single claim. However, such embodiments may be presented only if they involve a single inventive concept according to the obviousness-type double patenting practice for designs.” If the embodiments do not involve a single inventive concept, the the Office will issue a restriction requirement, which can present a risk for the applicant, and discussed below. The MPEP sets out a two part test for determining whether embodiments involve a single inventive concept:

(A) the embodiments must have overall appearances with basically the same design characteristics; and (B) the differences between the embodiments must be insufficient to patentably distinguish one design from the other.

MPEP 1504.05

The presentation of multiple embodiments has the effect of broadening the scope of the claim, because the single design patent claim only covers the elements common to all of the embodiments. This is great from an infringement standpoint, but it also makes the design patent more vulnerable to a validity attack.

As mentioned above, restriction requirements can present difficulties for design patent applicants. If the applicant does not file a divisional application for each restricted embodiment, the applicant could be dedicating the non-pursued embodiments to the the public. This was the case in Pacific Coast Marine Windshields Ltd. v. Malibu Boats, LLC, (Fed. Cir. 2014), where the Federal Circuit held that when subject matter is surrendered during prosecution of a design patent (such as by acceding to a restriction requirement), prosecution history estoppel prevents the patentee from “recapturing in an infringement action the very subject matter surrendered as a condition of receiving the patent.” e claimed invention.

In Pacific Coast Marine, during prosecution of the patent in suit (D689782) the Examiner identified five separate embodiments, but the applicant protected only two, leaving the other three embodiments unprotected.

Just because one can include multiple embodiments in a design application does not mean it is always a good idea. Thought should be given to whether the same protection can be achieved through a single embodiment with unimportant details shown in dashed lines (and thus excluded from the scope of the claims), and/or whether multiple applications would would provide better protection (albeit at a higher cost). Multiple embodiments can complicate both validity and infringement determinations.

Exceptional Does Not Mean “Wrong” — Otherwise Every Case Would be Exceptional

In Spineology Inc. v. Wright Medical Technology, Inc., [2018-1276] (December 14, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed the denial of Wright Medical Technology, Inc.’s motion for attorney fees under 35 U.S.C. § 285, finding no abuse of discretion.

The district court issued a claim construction order in, acknowledging that the parties disputed construction of the term “body,” but it declined to

adopt either party’s construction. Wright and Spineology then filed cross-motions for summary judgment on infringement. Recognizing the alleged infringement depended on how “body” was construed, the district court

construed “body” consistent with Wright’s noninfringement position and granted Wright’s motion. Wright then moved for attorney fees, arguing Spineology’s proposed construction of “body,” its damages theories, and its litigation conduct rendered this case “exceptional” under § 285. The district court denied the motion, determining that, while ultimately the court rejected Spineology’s proposed construction, it was not so meritless as to render the case exceptional. It similarly determined the arguments

made by Spineology to support its damages theory were not so meritless as to render the case exceptional. The district court concluded that n]othing about this case stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of Spineology’s litigating position or the manner in which

the case was litigated.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that, while Spineology’s proposed construction of “body” was ultimately rejected at summary judgment, the attempt was not so meritless as to render the case exceptional. The Federal Circuit stressed that a party’s position ultimately need not be correct for them not to standout. The Federal Circuit noted that Wright was hardly in a position to complain about Spineology’s continuing to pursue a construction not adopted by the district court in the claim construction order, since the district court declined to adopt Wright’s proposed construction as well.

Even though the case was resolved in summary judgment, Wright complained about Spineology’s damages theory,. While conceding that perhaps Spineology’s damages theories would not have prevailed, the Federal Circuit said “a strong or even correct litigating position is not the standard by which we assess exceptionality.”

The Federal Circuit noted that Wright was asking the court to basically decide the damages issues mooted by summary judgment in order to determine whether it ought to obtain attorney fees for the entire litigation. The Federal Circuit refused to do so — it will not force the district court, on a motion for attorney fees, to conduct the trial it never had, and the Federal Circuit declined to conduct the trial in the first instance.

The bottom line is exceptional does not mean “wrong” — otherwise every case would be exceptional.

Window into the Past

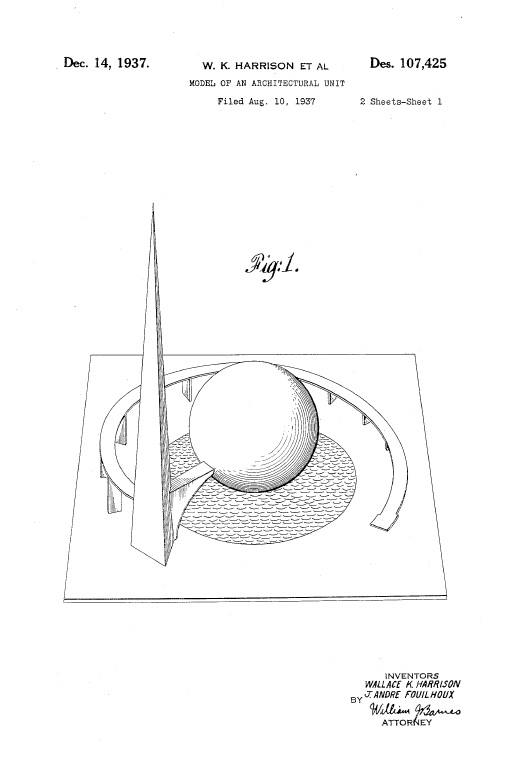

Patents can be an interesting window into the past. For example on December 14, 1937, U.S. Patent No. D107425 issued to Wallace K. Harrison and J. Andre Fouilhoux on a model of an architectural unit.

The design is of the Trylon, Perisphere, and Helicline that became the central symbol of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, reproduced by the millions on a wide range of promotional materials. and serving as the fairground’s focal point. The structures were razed and scrapped after the closing of the fair, and their materials repurposed into World War II armaments, but the image and the optimism for the future they were intended to convey, persist in the records of the USPTO.

Collateral Estoppel Exposes the Failure to have Legitimate Plan B

In Virtnex Inc. v. Apple, Inc., [2017-2490, 2017-2494] (December 10, 2018) the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB that claims 1–11, 14–25, and 28–30 of U.S. Patent No. 8,504,696 were unpatentable as obvious., noting that VirnetX was collaterally estopped from relitigating the threshold issue of whether prior art reference was a printed publication and because VirnetX did not preserve the only remaining issue of whether inter partes review procedures apply retroactively to patents that were filed before Congress enacted the America Invents Act.

During the pendency of VirnetX’s appeal, the Federal Circuit summarily affirmed seven final written decisions between VirnetX Inc. and Apple in which the Board found that RFC 2401 was a printed publication. The Federal Circuit said that Rule 36 summary dispositions could be the basis collateral estoppel, and that the only issue was whether the printed publication issue was necessary or essential to the judgment in the prior cases. The Federal Circuit held that it was.

VirnetX also argued that it preserved in its opening brief the issue of whether inter partes review procedures apply retroactively to patents that were filed before Congress enacted the AIA, pointing to a single paragraph in its Opening Brief, filed prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in Oil States. The Federal Circuit said that this paragraph raised the specific question later decided in Oil States, and under a very generous reading, the paragraph also arguably raises a general challenge under the Seventh Amendment, but it in no way provides any arguments specifically preserving the retroactivity issue.

The Federal Circuit concluded that VirnetX did not preserve the issue of whether inter partes review procedures apply retroactively to patents that were filed before Congress enacted the AIA and that, therefore, the conclusion that VirnetX was collaterally estopped from raising the printed

publication issue resolved all other issues in the appeal. The Federal Circuit affirmed.

The lesson, of course, is to correctly predict the future and simply preserve the issues you will need. Virtnex can hardly be faulted for not preserving the issue, when they had a more substantive issue before it, buy it always pays to have a legitimate Plan B.

Normal Double Patenting Rules Don’t Apply When the Patents Straddle the URAA

In Novaritis Pharmaceuticals Corporation v. Breckenridge Pharmaceutical Inc., [2017-2173, 2017-2175, 2017-2176, 2017-2178, 2017-2179, 2017-2180, 2017-2182, 2017-2183, 2017-2184] (December 7, 2018), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court, determining that the law of obviousness-type double patenting does not require a patent owner to cut down the earlier-filed, but later expiring, patent’s statutorily-granted 17-year term so that it expires at the same time as the later-filed, but earlier expiring patent, whose patent term is governed under an intervening statutory scheme of 20 years from that patent’s earliest effective filing date.

Applying Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., which held that a later-filed but earlier-expiring patent can serve as a double patenting reference for an earlier-filed but later-expiring patent, the district court found U.S. Patent No. 6,440,990 to be a proper double patenting reference for the earlier filed U.S. Patent No. 5,665,772, which had a longer term because of a change in the statutory term.

The Federal Circuit said that Gilead addressed a question that was not applicable in the present case — in Gilead, the Federal Circuit concluded that, where both patents are post- URAA, a patent that issues after but expires before another patent can qualify as a double patenting reference

against the earlier-issuing, but later-expiring patent. In contrast, in the present case Novartis owns one pre-URAA patent (the ’772 patent) and one post-URAA patent (the ’990 patent), and the 17-year term granted to the ’772 patent does not pose the unjustified time extension problem that was the case for the invalidated patent in Gilead.

[T]he present facts do not give rise to similar patent prosecution gamesmanship because the ’772 patent expires after the ’990 patent only due to happenstance of an intervening change in patent term law. Both the ’772 and the ’990 patents share the same effective filing date of

September 24, 1993. If they had been both pre-URAA patents, the ’990 patent would have expired on the same day as the ’772 patent by operation of the terminal disclaimer Novartis filed on the ’990 patent, tying its expiration date to that of the ’772 patent. And if they had been

both post-URAA patents, then they would have also both expired on the same day. Thus, the current situation does not raise any of the problems identified in our prior obviousness-type double patenting cases. At the time the ’772 patent issued, it cannot be said that Novartis improperly

captured unjustified patent term. The ’990 patent had not yet issued, and the ’772 patent, as a pre-URAA patent, was confined to a 17-year patent term.

The Federal Circuit concluded that in this particular situation where we have an earlier filed, earlier-issued, pre-URAA patent that expires after

the later-filed, later-issued, post-URAA patent due to a change in statutory patent term law, it would not invalidate the challenged pre-URAA patent by finding the post-URAA patent to be a proper obviousness-type double

patenting reference.

Petitioner is Entitle to Remedy Against Defaulting ITC Respondents

In Laerdal Medical Corp. v. ITC, [2017-2445] (December 7, 2018), the Federal Circuit reversed the ITC’s denial of remedies against defaulting respondents because Laerdal failed to properly plead its trade dress claim.

, [2017-2445] (December 7, 2018), the Federal Circuit reversed the ITC’s denial of remedies against defaulting respondents because Laerdal failed to properly plead its trade dress claim.

The Commission concluded that, even when the pleaded facts were presumed true, Laerdal failed to show that any of the defaulting respondents violated § 1337 with respect to the alleged trade dresses and copyrights. Specifically, the Commission found that Laerdal failed to plead sufficiently (1) that it suffered the requisite harm, (2) the specific elements that constitute its trade dresses, and (3) that its trade dresses were not functional.

Thus, despite approving the ALJ’s initial determination finding all respondents in default and despite requesting supplemental briefing solely related to the appropriate remedy, the Commission issued Laerdal

no relief on those claims or against any of the respondents named in those claims. Laerdal appeals the Commission’s termination of its trade dress claims, contending the Commission acted in violation of § 1337(g)(1) by terminating the investigation and issuing no relief for its trade dress claims against defaulting respondents.

19 U.S.C. § 1337(g)(1) provides that in the event of a default, the Commission shall presume the facts alleged in the complaint to be true and shall, upon request, issue an exclusion from entry or a cease and desist

order, or both. The Federal Circuit concluded that statute, on its face, unambiguously requires the Commission to grant relief against defaulting respondents, subject only to public interest concerns, if all prerequisites of § 1337(g)(1) are satisfied. The statute’s plain text, surrounding context, purpose, and legislative history, as well as the Commission’s own

prior decisions, supported this conclusion.

Judicially Created Double Patenting Does Not Limit Statutory Patent Term Extension

In Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures, LLC, [2017-2284] (December 7, 2018), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s determination that obviousness- type double patenting does not invalidate an otherwise validly obtained patent term extension (PTE) under §156.

After Ezra filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) relating to

a generic version of Novartis’s Gilenya® multiple sclerosis drug, Novartis sued Ezra for infringement of claims 9, 10, 35, 36, 46, and 48 of U.S. Patent No. 5,604,229. Ezra responded by attacking the validity of the patent.

Ezra first argued that Novartis violated § 156(c)(4) because, two patents were extended as the extension of the ’229 patent’s term “effectively” extended U.S. Patent No. 6,004,565’s term as well, because the ’229 patent covers a compound necessary to practice the methods claimed by the ’565 patent. Ezra argued that this violated its “right” to practice the ‘565 patent upon its expiration. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument finding that §156 gives the patent owner discretion to select which of several patents to extend, and that additional words should not be read into the statute to limit this discretion.

Ezra also argued that the ’229 patent is invalid due to obviousness-type double patenting because the term extension it received causes the ’229 patent to expire after Novartis’s allegedly patentably indistinct ’565 patent. The Federal Circuit noted that a straightforward reading of §156 mandates a term extension so long as the other enumerated statutory requirements for a PTE are met. The Federal Circuit further noted that the difference in language for patent term adjustment (PTA) under §154(b) and PTE under §156 support the conclusion that a patent term extension under §156 is not foreclosed by a terminal disclaimer.”

The Federal Circuit noted that obviousness-type double patenting is a “judge-made doctrine” that is intended to prevent extension of a patent beyond a “statutory time limit,” and declined Ezra’s invitation to use the judge-made doctrine to cut off a statutorily-authorized time extension.

C&D Letters Sufficient to Establish Personal Jurisdiction

In Jack Henry & Associates, Inc. v. Plano Encryption Technologies LLC, [2016-2700] (December 7, 2018), the Federal Circuit reversed the dismissal of the action for lack of personal jurisdiction, and remanded for further proceedings.

PET is a Limited Liability Company established in the State of Texas, and is registered to do business throughout Texas, with its registered address in Plano, Texas, in the Eastern District of Texas. PET’s sole business is to enforce its intellectual property. After receiving letters alleging infringement, Jack Henry and its customers brought the declaratory judgment action in the Northern District of Texas.

The district court granted PET’s motion for dismissal, stating that PET’s actions do not subject it to personal jurisdiction in the Northern District of Texas, noting that while such letters might be expected to support an assertion of specific jurisdiction over the patentee because the letters are purposefully directed at the forum and the declaratory judgment action arises out of the letters, the Federal Circuit has held that, based on policy considerations unique to the patent context, letters threatening suit for patent infringement sent to the alleged infringer by themselves do not suffice to create personal jurisdiction.

The Federal Circuit identified three relevant factors: (1) whether the defendant “purposefully directed” its activities at residents of the forum; (2) whether the claim “arises out of or relates to” the defendant’s activities within the forum; and (3) whether assertion of personal jurisdiction is “reasonable and fair.” It said that the first two factors comprise the “minimum contacts” portion of the jurisdictional framework, and that it has held that the sending of a letter that forms the basis for the claim may be sufficient to establish minimum contacts, and PET’s counsel conceded as much at oral argument.

The analysis then turned to whether assertion of personal jurisdiction is “reasonable and fair.” The Federal Circuit noted that PET is subject to general jurisdiction in the state of Texas and is registered to do business throughout the state, and that it has not asserted that jurisdiction in the Northern District is inconvenient or unreasonable or unfair.

The Federal Circuit said that the burden befalls PET, as the source of the minimum contacts, to make a “compelling case” that the exercise of jurisdiction in the Northern District would be unreasonable and unfair. However, PET did not argue that litigating in the Northern District would be unduly burdensome, or that any of the other factors supports a finding that jurisdiction would be unfair. The Federal Circuit concluded that PET has met the minimum contacts requirement without offense to due process.