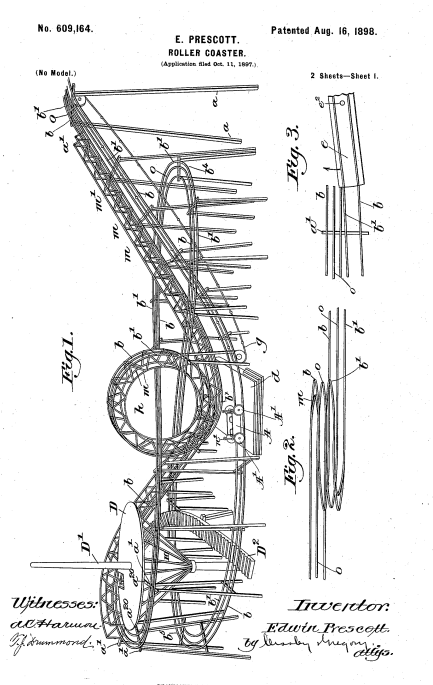

On August 16, 1898, Edwin Prescott received U.S. Patent No. 609,164 on a roller coaster with a loop-the-loop:

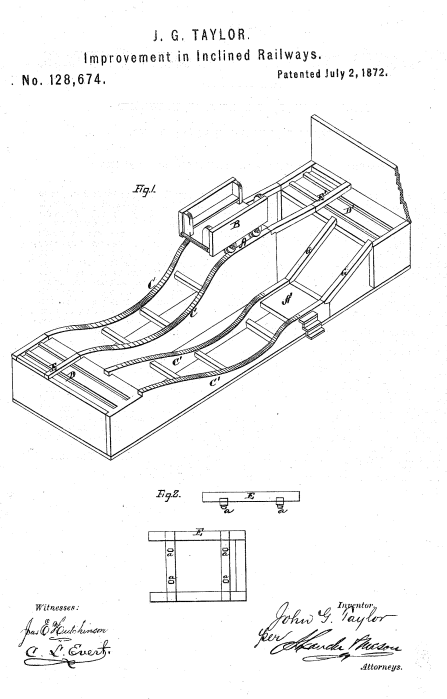

There are earlier patents on roller coasters without the loop-the-loop, including John G. Taylor’s 1872 U.S. Patent No. 128,674 on Improvement in Inclined Railways:

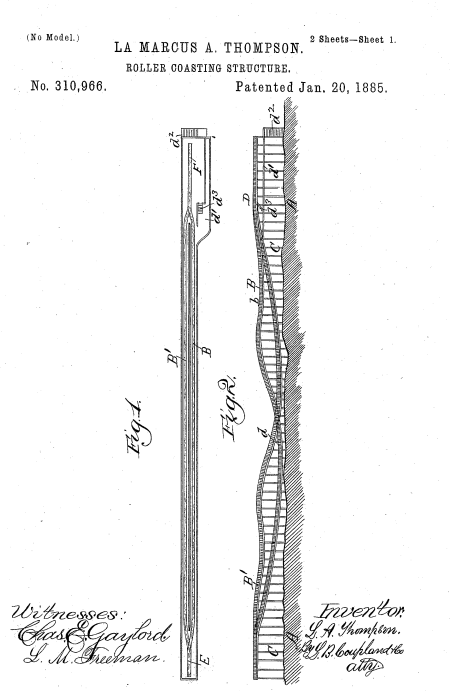

and LaMarcus A. Thompson’s 1885 U.S. Patent No. 310,966 on a Roller Coasting Structure:

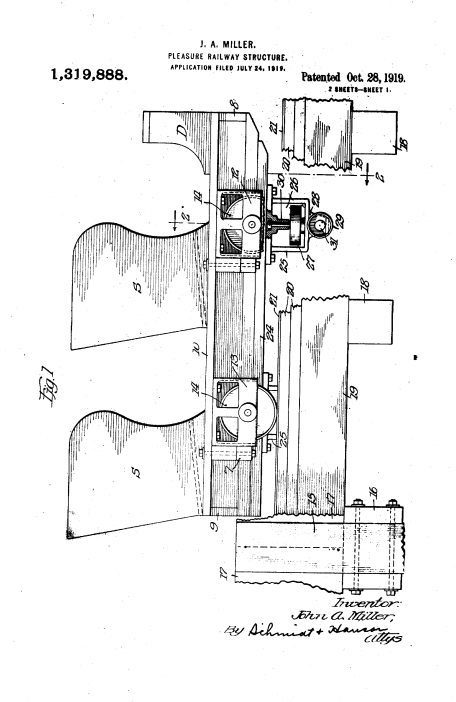

Subsequently, in 1919, John A . Miller’s U.S. Patent No. 1,319,888 on a Pleasure Railway Structure introduced the idea of wheels below the track as well, to maintain the cars on the track:

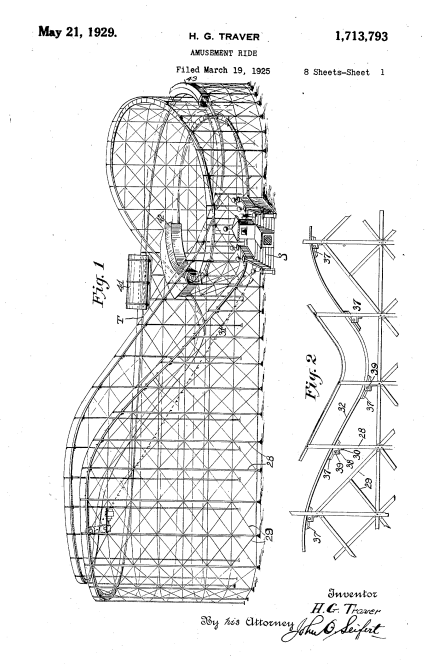

By 1929, H. G. Traver’s U.S. Patent No. 1,713,793 on an Amusement Ride looks more like the modern roller coasters we are used to: