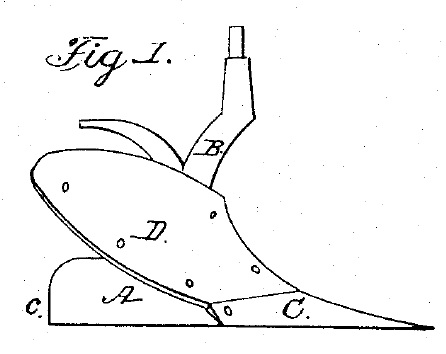

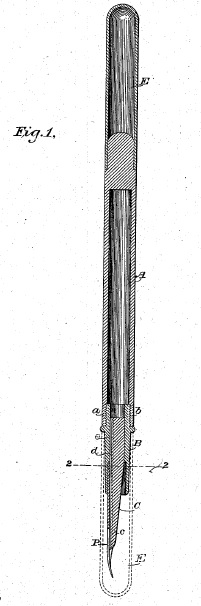

On February 21, 1865, U.S. Patent No. 46,454 issued to John Deere on a Plow:

February 20 Patent of the Day

February 19 Patent of the Day

February 18 Patent of the Day

February 17 Patent of the Day

February 16 Patent of the Day

February 15 Patent of the Day

February 14 Patent of the Day

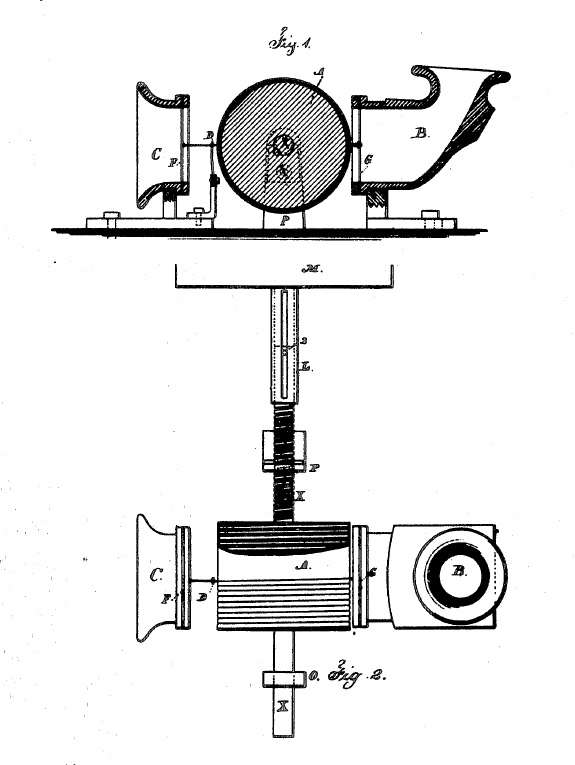

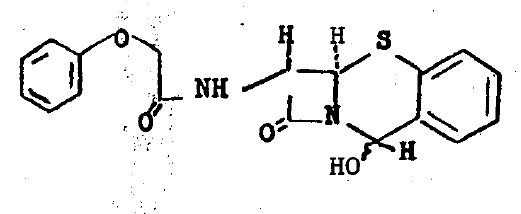

On February 14, 1871, U.S. Patent No. 111,798 issued to Thomas Adams on an Improvement in Chewing-Gum.

Adams conceived the idea while working as a secretary to former Mexican leader Santa Anna, who chewed a natural gum called chicle. After failing to turn it to a rubber suitable for tires, he made the chicle into a chewing gum called Chiclets.