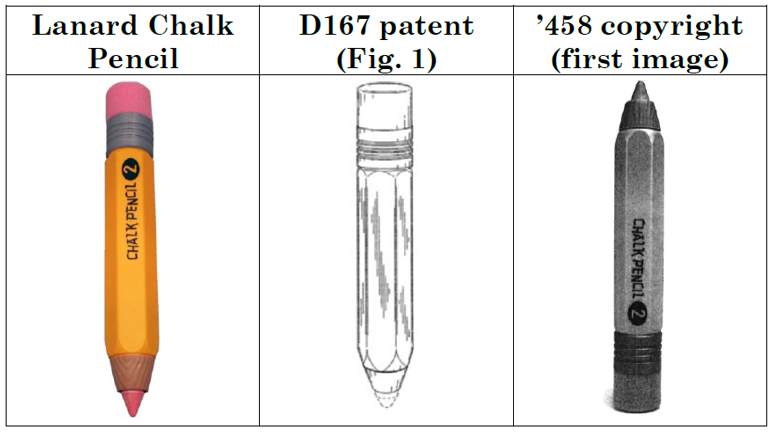

In Lanard Toys Limited v. Dolgencorp LLC, [2019-1781](May 14, 2020), the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment for defedants with respect to Lanard’s claims for infringement of U.S. Patent No. D671167, infringement of Copyright Reg. No. VA 1-794-458, trade dress infringement, and statutory and common law unfair competition.

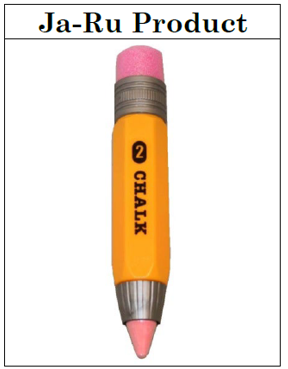

Defendant’s used the Lanard Chalk Pencil as a “reference sample” in designing its product.

Lanard sued for: (1) copyright infringement; (2) design patent infringement; (3) trade dress infringement; and (4) statutory and common law unfair competition under federal and state law. On cross motions for summary judgment relating to all claims, and the district court granted Defendants motion, holding that Defendants’ product does not infringe the D167 patent, that the ’458 copyright is invalid and alternatively not infringed by Ja-Ru’s product, that Ja-Ru’s product does not infringe Lanard’s trade dress, and that Lanard’s unfair competition claims fail because its other claims fail.

Determining whether a design patent has been infringed is a two-part test: (1) the court first construes the claim to determine its meaning and scope; (2) the fact finder then compares the properly construed claim to the accused design. In comparing the patented and accused design, the “ordinary observer” test is applied—i.e., infringement is found if in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other. The infringement analysis must compare the accused product to the patented design, not to a commercial embodiment.

On appeal Lanard argued that the district court court erred in its claim construction by eliminating elements of the design based on functionality and lack of novelty. Second, Lanard argued that the court erred in its infringement analysis by conducting an element-by-element comparison rather than comparing the overall designs. Third, Lanard argues that the court used a rejected “point of novelty” test to evaluate infringement.

The Federal Circuit said that where a de-sign contains both functional and non-functional elements, the scope of the claim must be construed in order to identify the non-functional aspects of the design as shown in the patent, and found that the district court followed its claim construction directives “to a tee.” In an effort to clarify the scope of the protected subject matter, the court considered the functional features of the design, as well as the functional purpose of the writing utensil as a whole, including its proportions, considering the functionality of the “conical tapered piece,” “elongated body,” “ferrule,” “eraser,” “the design’s functional purpose as a writing utensil,” “the general thickness of the design,” and “the circular opening at the tapered end”). The district court meticulously acknowledged the ornamental aspects of each functional element, including “the co-lumnar shape of the eraser, the specific grooved appearance of the ferrule, the smooth surface and straight taper of the conical piece, and the specific proportional size of these elements in relation to each other.

The Federal Circuit noted that the district court considered its instruction that it is helpful to point out “various features of the claimed design as they relate to the accused design and the prior art, and considered the numerous prior art references cited by the examiner on the face of the D167 patent, as well as other designs identified by defendants, all directed to the shape and design of a pencil. The district court thus recognized that “the overall appearance of Lanard’s design is distinct from this prior art only in the precise proportions of its various elements in relation to each other, the size and ornamentation of the ferrule, and the particular size and shape of the conical tapered end. In so doing, the district court fleshed out and rejected Lanard’s attempt to distinguish its patent from the prior art by importing the “the chalk holder function of its design” into the construction of the claim.

The Federal Circuit said that the court noted that Lanard’s problem was that the design similarities stem from aspects of the design that are either functional or well-established in the prior art. The district court found that “the attention of the ordinary observer would be drawn to those aspects of the claimed de-sign that differ from the prior art, which would cause the distinctions between the patented and accused designs to be readily apparent. Based upon the evidence presented, the district court found that no reasonable fact finder could find that an ordinary observer, taking into account the prior art, would believe the accused design to be the same as the patented design.

The Federal Circuit rejected Lanard’s argument that Complaint that the district court conducted an element-by-element comparison “in lieu of” a comparison of the overall design and appearance. The Federal Circuit noted that while the “ordinary observer” test is not an element-by-element comparison, it also does not ignore the reality that designs can, and often do, have both functional and ornamental aspects. Under the “ordinary observer” test, a court must consider the ornamental features and analyze how they impact the overall design, and the Federal Circuit said that is what the district court did, noting that in comparing the overall design of the patent with the overall design of the defendants’ product, the court necessarily considered how the ornamental differences in each element would impact the ordinary observer’s perception of the overall designs. The district court refocused its analysis on the correct context—the impact of the ornamental differences on the overall design—and concluded that “the differences between the patented and accused design take on greater significance.

The Federal Circuit also disagreed with Lanard’s contention that the court reinstated the “point of novelty” test in its infringement analysis. The Federal Circuit said it was true that it has rejected the notion that the “point of novelty” test is a free-standing test for design patent infringement, but added that it has never questioned the importance of considering the patented design and the accused design in the context of the prior art. The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court correctly balanced the need to consider the points of novelty while remaining focused on how an ordinary observer would view the overall design.

The Federal Circuit concluded that Lanard’s position is untenable because it seeks to exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil and thus extend the scope of the D167 patent far beyond the statutorily protected “new, original and ornamental design.

On the copyright issue, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the chalk holder was a useful article, and agreed with defendants that Lanard failed to identify any feature incorporated into the design of its copyright that is separate from the utilitarian chalk holder and that Lanard is merely attempting to assert copyright protection over the useful article itself. The Federal Circuit said that Lanard was essentially seeking to assert protection over any and all expressions of the idea of a pencil-shaped chalk holder, but that copyright protection does not extend to an “idea.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(b). On the trade dress issue, the Federal Circuit began by outlining the elements of a claim: To prevail on a claim for trade dress infringement, a plaintiff must prove three things: (1) that the trade dress of two products is confusingly similar; (2) that the features of the trade dress are primarily non-functional; and (3) that the trade dress has acquired secondary meaning. The district court found that Lanard could not provide sufficient evidence that the Lanard Chalk Pencil has acquired secondary meaning. Lanard relied exclusively on defendants’ copying and its own sales as evidence of secondary meaning, and the district court found that the evidence “woefully fails” to show secondary meaning. Lanard never presented evidence or argument that distinguished between end-users versus wholesalers and retail stores, nor evidence of efforts to promote its product through its sales force. The Federal Circuit found that on this record, the district court correctly granted summary judgment on Lanard’s claim for trade dress infringement.